When we think of the Middle Ages we often imagine a world full of knights, castles and, of course, dragons. Sightings of dragons appear periodically in medieval chronicles such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle of AD.793 which mentions ‘dreadful fore-warnings…whirlwinds, and fiery dragons flying across the firmament”. This 15th century illustrated version of Pliny’s ‘Natural History’ (written in 1st century AD and referenced throughout the Middle Ages) has a dragon in the initial for book eight, accompanied by other monstrous beasts such as a lion and an elephant.

![Msl/1896/1504, Pliny the Elder, Naturalis historia, Italy, [ca. 1465], © V&A Museum.](https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/msl-1896-1504-pliny-resized_5ef04e4e96c2d5e4671a6c728ae1a9c6-290x218.jpg)

“…continually at variance with them, and evermore fighting, and those of such greatnesse, that they can easily claspe and wind round about the Elephants, … the dragons ware hereof, entangle and snarle his feet and legges first with their taile: the Elephants on the other side, undoe those knots wiht their trunke as with a hand..”

A Medieval person might be justified in being fearful of encountering the serpent-like figure of a dragon in real life!

When looking through the V&A’s beautiful collection of Medieval manuscripts and manuscript cuttings, images of dragons are a regular, and always thrilling, find. They don’t seem to go out of fashion despite the variety in decorative schemes in manuscript illumination throughout the Middle Ages. Prepare to gawp in wonder at these marvellous beasts.

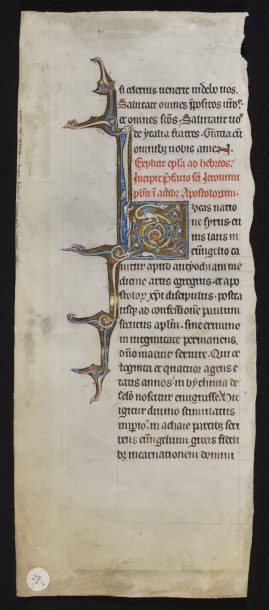

Interlacing decoration is characteristic of medieval manuscripts. It was influenced by Celtic and Germanic art and was popular from around the 8th century. The sinewy body of dragons were perfect for such adornment as seen in these manuscripts from the 13th century.

Decorated initials developed to feature figures (inhabited initials) or a narrative scene (historiated initials). The shape of an initial H (inhabited with figures of the virgin and child) from this 14th century manuscript is formed by a dragon.

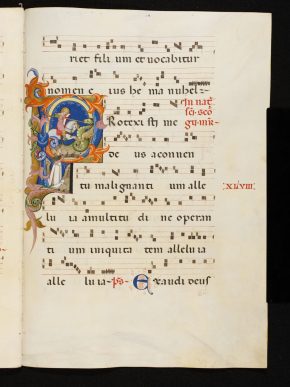

Images of saints (some of whom were renowned for run-ins with dragons) often appear in Medieval manuscripts. In this 14th century gradual (a book of the music used in the Mass) Saint George battles a dragon. The historiated initial P starts the prayer ‘Protexisti me, Deus…’ (Thou hast protected me, O God, from the assembly of the malignant). George is shown protecting the maiden from her dragony fate.

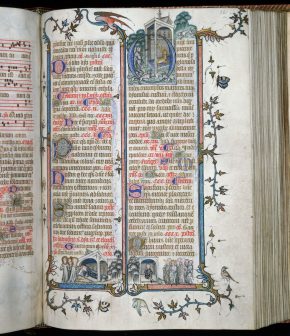

Decoration increasingly spread over the whole page of a manuscript, spreading out from the initials. Amongst its varied ornamentation, the 14th century St Denis missal has decorated finials in the shape of dragons on a number of pages

As you can see from the St Denis missal, pictures were now also found in the margins of manuscripts. These are called marginalia and flourished in the later Middle Ages. As well as the birds and beasts in the St Denis missal, supernatural or grotesque figures were also popular.

This very fine dragon features in the margins of this 15th Century antiphoner (a type of choirbook). You can read the name of Michael the Archangel beginning with the decorated initial, with the dragon highlighting his dragon-slaying fame by the blood spurting from its breast.

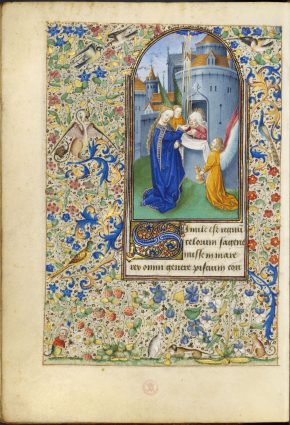

In the late years of the Middle Ages decoration could cover an entire page, with beautifully intricate margins surrounding a central scene. They would often feature realistic images of birds, insects and fruit, but grotesques were still popular and a dragon can be spotted in this French book of hours from around 1470.

Mysterious and beautiful, dragons inhabited the world of medieval manuscripts for hundreds of years. They can be symbols of a spiritual evil that attention to these texts would help you overcome, but perhaps could also be symbols of wisdom and protection, guarding the treasure of the words on the page.

What a lovely article, beautifully balancing the line between accessibility and scholarly learning. Fabulous illustrations, thank you!