This blog is by Anne-Margaux Illido, a postgraduate student in Art History and Museum Curating at the University of Sussex, currently completing a placement at the V&A with Zorian Clayton and Dawn Hoskin from the LGBTQ Working Group.

When discussing the LGBTQ-related topics I could address in a blog post, I was drawn towards the current V&A exhibition Balenciaga: Shaping Fashion to further explore how the great designer’s sexuality may have deeply influenced his design and production.

Cristóbal Balenciaga (1895-1972) was private and enigmatic, and his “religious convictions made him a very discreet and humble person” according to fashion designer Hubert de Givenchy.[1] The ‘master’ allowed few public appearances, however, the people close to him knew about his homosexuality and the relationships he developed with some of his male business partners.

During his lifetime, Balenciaga had several love affairs with men, notably with his two main milliners, Ramon Esparza, and Wladzio Jawrorowski d’Attainville, with whom he had his most intense relationship, professionally as well as privately. He was a Franco-Polish aristocrat and milliner who co-founded then designed hats for the Balenciaga house from the 1920s to 1948 – hats being an essential component of female outfits at that time.[3] According to Elisa Erquiaga, one of Balenciaga’s dressmakers, “[D’Attainville] was very handsome and well-educated and we all knew, but nobody spoke about it in the studio.”[2]

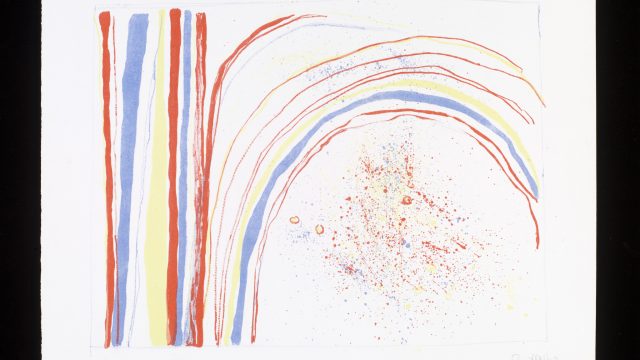

designed by Balenciaga, 1955-60. ©Victoria & Albert Museum

D’Attainville became a trustworthy source of inspiration, a kind of Pygmalion for the designer, as he was “refining his persona and finishing its seams” according to fashion writer Judith Thurman.[4]

He was undoubtedly Balenciaga’s great love. The pair were inseparable and lived together along with the designer’s mother. Due to his aristocratic background – his Napoleonic ancestor was the Duke of Rivoli and Prince of Essling [5], d’Attainville was acquainted with various aristocrats and royalty all over Europe, and he probably contributed to expanding Balenciaga’s sophisticated clientele. However, when General Franco came to power and his wife and daughter began dressing at Balenciaga, the couple would have had to have been particularly careful.[6]

Because Balenciaga never married and kept his personal life strictly private, rumours occasionally abounded over his sexuality. The two biggest wounds in Balenciaga’s life were the triumph of Christian Dior’s ‘New Look’ in 1947, and the death of d’Attainville the year after.[7] D’Attainville’s death devastated Balenciaga to the point where he considered closing down his business, and was only dissuaded from retiring after an appeal from his great rival and friend, Dior.[8] Instead, from 1948 onwards, one could notice that Balenciaga’s fashion shows displayed a vast majority of black dresses, as a powerful symbol referring to his deceased lover. Miren Arzalluz, ex-curator at the Cristóbal Balenciaga Museum, interpreted that by doing so, Balenciaga imposed the mourning for his partner onto all the elegant women of his age, making wearing black become the wider embodiment of chic and the staple of the fashion world.

In 1937, before d’Attainville’s death, Harper’s Bazaar had already highlighted Balenciaga’s sexuality in the foreground after a spat with fellow fashion designer Coco Chanel. Chanel made the following incisive observation to a friend: “It is obvious that [Balenciaga] dislikes [women]; look at the way he conceals blouses under suits, just to expose the wrinkles in their necks”.[10] According to curator and fashion historian Dr Shaun Cole, charges like Coco Chanel’s against Balenciaga were frequently made against male designers. But what was Chanel referring to exactly: Balenciaga’s designing style, or his private life? Balenciaga indeed truly revolutionized women’s dress with his unique way of shaping and dressing their bodies.

Wool ‘sack’ dress by Balenciaga, Paris, 1957-8. ©Victoria & Albert Museum

His notable 1957 ‘sack dress’ was deeply controversial, and was seen as unflattering for women’s bodies, especially at the time when strong feminine curves were being valorised and certainly not concealed.

However, every design created by the master was meant to be adapted to the individual body, concealing physical imperfections and at the same time exposing the best qualities. Balenciaga himself said: “A woman has no need to be perfect or even beautiful to wear my dresses, the dress will do that for her”. Rather than harbouring any dislike for women, in fact his designs could be seen as evidence of the constant tribute he paid to real (if extraordinarily wealthy!) women and their diverse body shapes.

In 2013 Valerie Steele curated the exhibition A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk, investigating the significant role of LGBTQ communities and gay culture in fashion. She stated, “Although many designers are openly gay, the subject of fashion and homosexuality remains an open secret”.[11] Indeed, even if the fashion world remains partly closeted today, it has been largely dominated by gay male designers including Christian Dior, Yves Saint Laurent, Giorgio Armani, Gianni Versace, Alexander McQueen, Jean Paul Gaultier, Marc Jacobs, Karl Lagerfeld- the list goes on, with Balenciaga at the top as the ultimate designer’s designer. When the creations of LGBTQ people can still be easily stereotyped or minimized, “can something as important as one’s sexual identity ever be completely irrelevant to an individual’s creative work?”.[12]

Balenciaga: Shaping Fashion – Victoria & Albert Museum, until 18 February 2018.

[1] Myra Walker, « Hubert de Givenchy remembering Balenciaga », Balenciaga and His Legacy: Haute Couture From the Texas Fashion Collection (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006).

[2] Ernesto Delgado, « The most famous Basque gay: Cristóbal Balenciaga », LGBT & Gay friendly tours in the Basque country, http://ernestodelgadotours.blogspot.co.uk/2015/01/the-most-famous-basque-gay-cristobal.html [accessed 30 June 2017].

[3] See the V&A article on Balenciaga and hats, https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/balenciagas-hats.

[4] Judith Thurman, « The Absolutist: Cristóbal Balenciaga’s cult of perfection », The New Yorker, July 3, 2006, p. 62.

[5] Arzalluz Miren, Cristóbal Balenciaga: The Making of a Master (1895-1936) (London: Victoria & Albert Publishing, 2011), p. 142.

[6] Judith Thurman, « The Absolutist », p. 62.

[7] Ibid., p. 59.

[8] Ibidem.

[9] Justine Picardie, « The Victoria & Albert Museum Balenciaga exhibition », Haarper’s Bazaar (June 2017, collector edition for the V&A), p. 171.

[10] Marie-Andrée Jouve and Jacqueline Demornex, Balenciaga (London: Thames and Hudson, 1989).

[11] Valerie Steele, « A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk », A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk, exh. New York, Fashion Institute of Technology, 13 September 2013 – 4 January 2014 (New York: Yale University Press, 2013), p. 8.

[12] Ibidem.