‘A Third Gender: Beautiful Youths in Japanese Prints’ is an ambitious exhibition. It sets out to explore the complex issues of gender identity, social status and sexual relationships in Japan during the Edo period (1603-1868). It surpasses these objectives and provides a forum for discussion on gender identity and non-hetronorm ideologies. The exhibition’s title ‘A Third Gender’ refers to male adolescent youths, called wakashu, who inhabited a unique position in Edo society. Wakashu were boys from any class, who prior to their ‘coming of age’ ceremony, could be the objects and agents of sexual desire for both men and women.[i] In their appearance, as well as in their sexual and social roles, they occupied an alternative ‘third gender’ status, which was distinct from men and women.

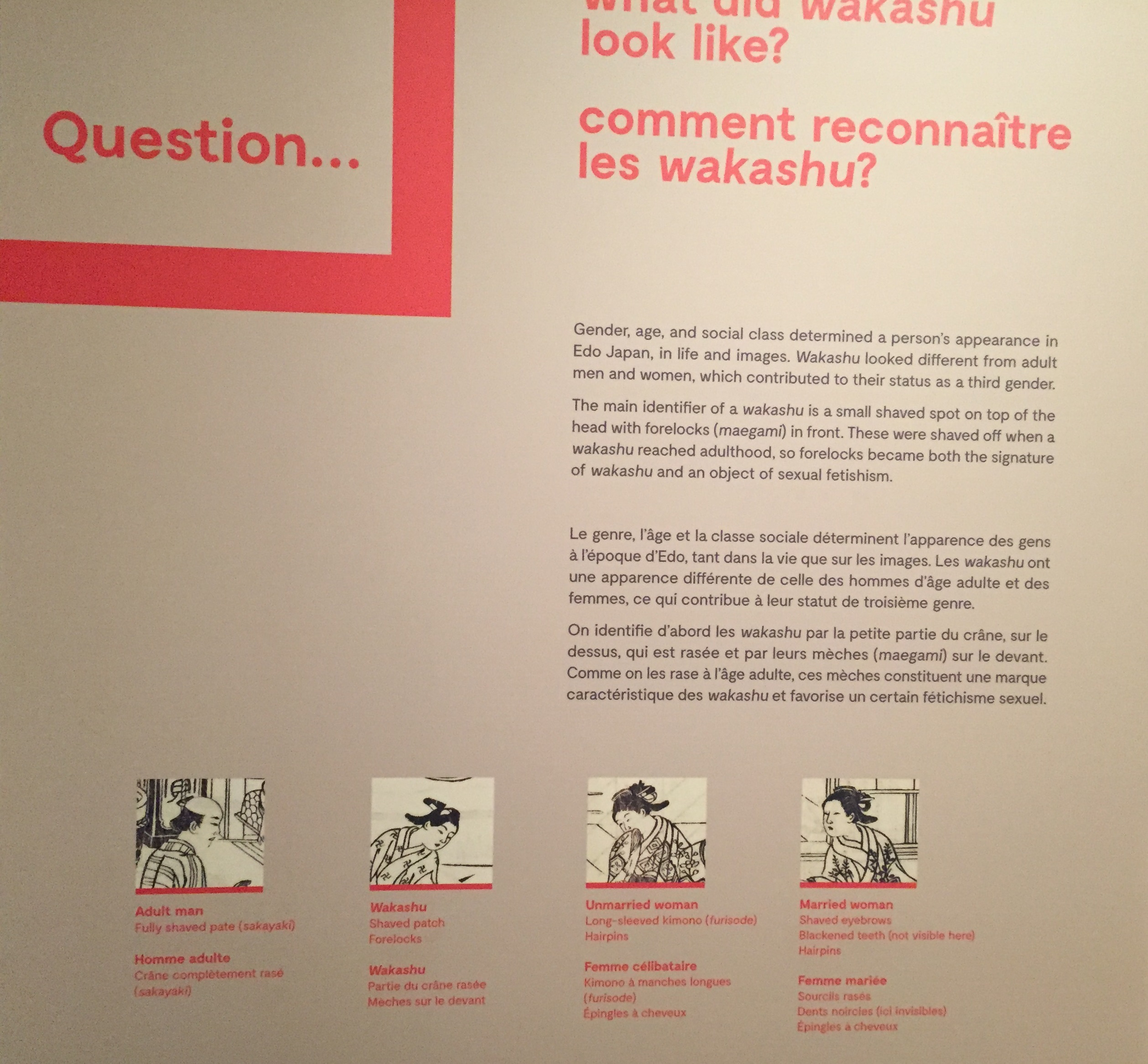

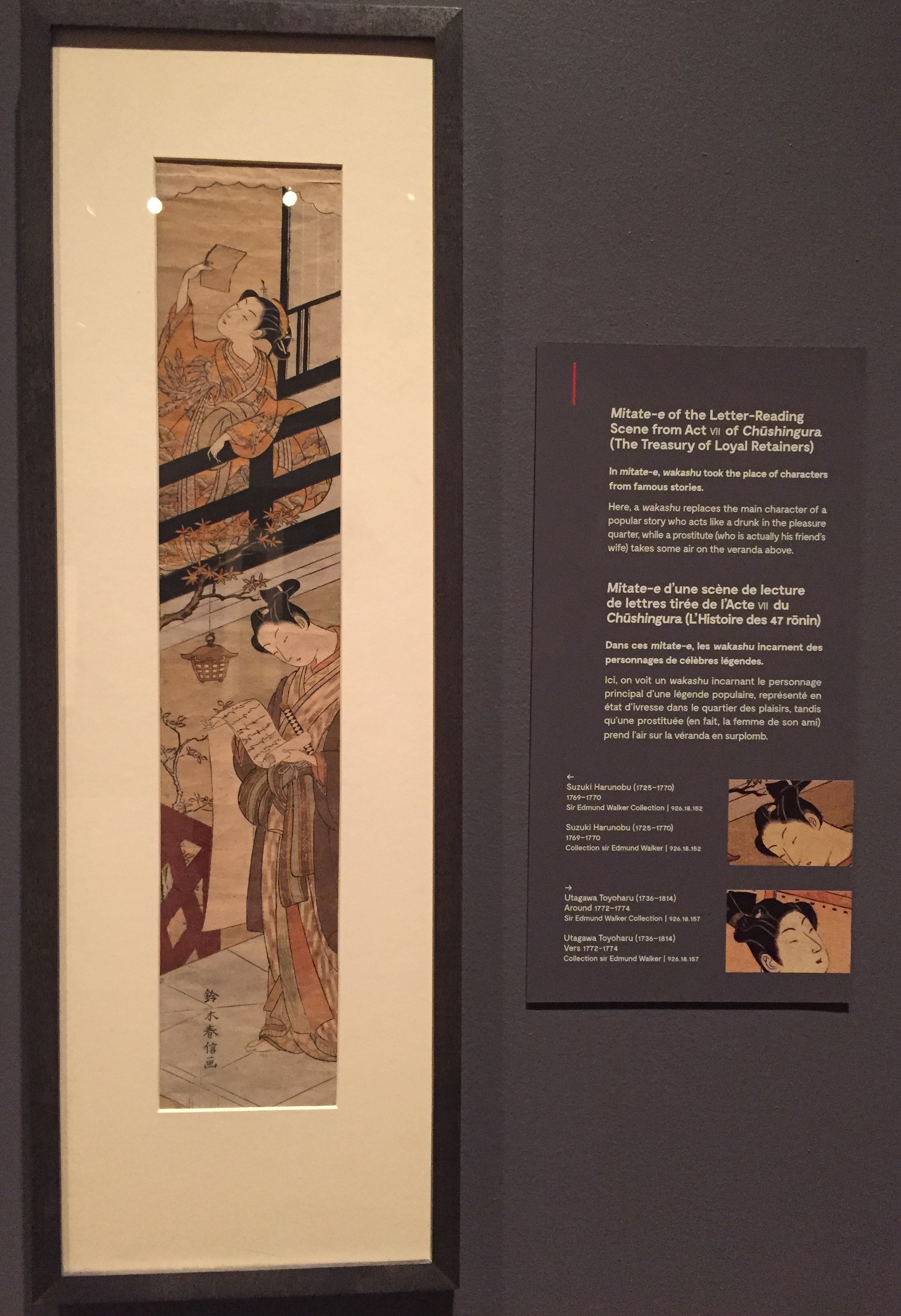

‘A Third Gender’ is composed of three main sections. The first introduces the visitor to the wakashu. Providing visitors with the tools to identify the wakashu’s distinguishing features of a shaved pate and forelocks (fig.2). This section also sets out the social sexual conventions and values of Edo, providing context to support contemporary audiences’ understanding of wakashu.

The last section examines the role of women as cross dressers. It concludes by examining the impact of 19th-century Western values on Japanese culture and the emerging ‘normalisation’ of a binary gender structure and heterosexual relationships.[1] To highlight that it is not only in Japan in which ‘a third gender’ exists, the exhibition shows examples of ‘third genders’ in different cultures and countries; such as the First People of North America’s ‘Two-Spirit’ individuals, South Asia’s Hijras or Benin’s Mino. There are thoughtful interactives which provide visitors with the opportunity to voice their thoughts on gender and contribute to a broader discussion on gender identity.

Despite studying Japanese woodblock prints at university and having seen representations of the erotic playgrounds of the ‘floating world’ at the British Museum’s Shunga: Sex and pleasure in Japanese art exhibition, I found that the history of the wakashu was entirely new to me. This exhibition does a fantastic job of introducing and identifying the wakashu, as well as presenting their unique ‘sexually ambidextrous’ role within the framework of the Edo social strata. Wall graphics, panel and label text and images are brilliantly deployed throughout the exhibition (figs.1,2 and 3). They work together to raise and answer issues and to signpost the visitor seamlessly through what could be a complex and alien subject matter. The exhibition sadly contains few personal artefacts from the Edo period with none directly owned by a wakashu. However this deficit is balanced out by an abundance of pertinent prints and their varied representations of the wakashu and their sexual partners.

In practical terms ‘A Third Gender’ is a great case study of how to make the most of your museum’s collection. It was produced in-house with limited resources and in a restricted space. It comprises only the Royal Ontario Museum’s (ROM) objects with no external loan items used to bolster its narrative. It is an admirable example of how collection research can uncover new narratives to enliven interest and attract new audiences. It demonstrates a successful synergy between the curator, the interpretation team, plus local community groups on how to astutely communicate a complex subject to a broad audience. This exhibition has helped ushered in welcome changes at the ROM in how it provides for, represents and engages with LBTBQ+ audiences.

I came to be reviewing ‘A Third Gender’ exhibition in Toronto thanks to the support of the ACDP training fund and the V&A Museum of Childhood. There are several issues explored in this exhibition that I am considering for my upcoming exhibition on gender and childhood. The central one is how historical representations of gender are interpreted in a contemporary context. Another is how a niche subject can be made relevant to current and diverse audiences. Under Dr. Asato Ikeda and Dr. Sascha Priewe’s careful stewardship, the wakashus made relevant to current audiences, but are presented within their social and historical context. Contemporary pronouns, language and terminology were not used to describe or explain Edo’s gender roles. And this practice helped to ensure that Edo’s gender roles remained distinct from contemporary values and associations. It is testament to the team’s work with LGTBQ+ communities that they developed an exhibition which was sensitive to current audiences and provides a safe space to discuss issues of gender (fig. 4).

‘A Third Gender: Beautiful Youths in Japanese Prints’ exhibition at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto ran from May to November 2016 and is now on display at the Japan Society in New York until 11 June 2017.

The exhibition was curated by Dr. Asato Ikeda, Assistant Professor at Fordham University. It was developed with Dr. Sascha Priewe, Managing Director – Culture Centres (ROM Ancient Cultures, ROM World Art &Culture, ROM Textiles & Fashions) and Dr. Joshua S. Mostow, Professor of Pre-Modern Japanese Literature and Art at the University of British Columbia.

There is an exhibition catalogue available: ‘A Third Gender: Beautiful Youths in Japanese Edo-period Prints and Paintings (1600-1868)’. Joshua S. Mostow and Asato Ikeda, with the assistance of Ryoko Matsuba. Toronto: ROM Press, 2016.

[1] Wall panel. The End of the Edo period. A Third Gender: Beautiful Youths in Japanese Prints, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada

[i] Wall Panel. How old were wakashu? A Third Gender: Beautiful Youths in Japanese Prints, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada

[ii] Wall panel How did nanshoku (“male love”) work? A Third Gender: Beautiful Youths in Japanese Prints, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada