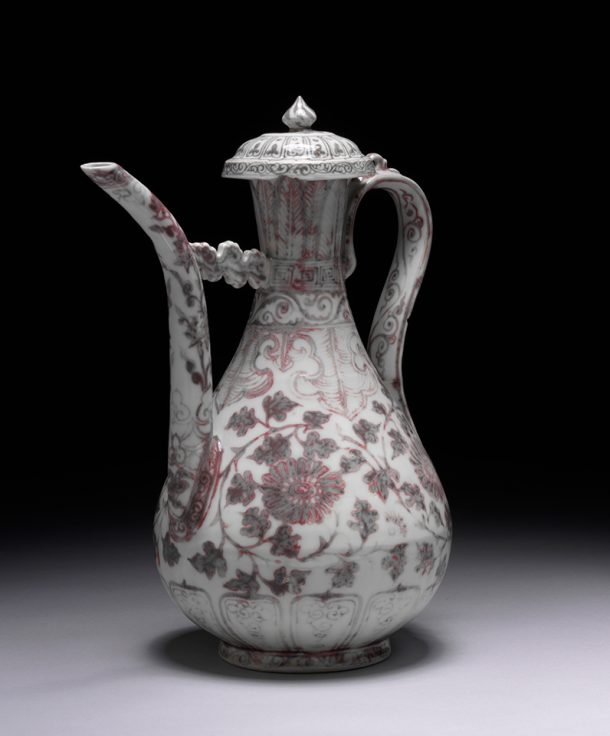

We all know that lids to jars can be frustratingly easy to misplace, so we’re thrilled to have recently found a lid which we didn’t even know was lost! Especially as it belongs to one of the most prominent pieces of Chinese porcelain in the V&A’s collections – a 14th century pouring vessel, commonly known as kendi.

The kendi is a familiar form of vessel shape from Asia, defined by its squat bulbous body, a neck through which it is filled, and a short, fat spout that narrows at the end to a small opening. Kendi is a Malay term that is believed to derive from the Sanskrit kundika (water pot). Originally used by travelling Buddhist monks as a ritual vessel that contained holy water, it later became a domestic drinking vessel produced in a variety of materials and across huge geographical areas, enjoying popularity especially in Southeast Asia.

The example with the missing lid was made by potters in the ceramic kilns of Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province in the 14th century. That was where the court of the newly founded Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) established an official porcelain factory, an important decision that would change porcelain production for centuries to come. Ceramic making continued in a variety of other kilns all over the country, but the scale of production at Jingdezhen, combined with the imperial court’s endorsement, enabled it to surpass all other centres of production.

The imperially sponsored kilns fired up technological innovation and our kendi is testimony to one of these: the use of the colour red as a decorative design feature on the porcelain clay body. Scientific analysis has revealed that the red pigment used during this period is composed of high concentrations of copper and arsenic but no tin, which makes it a highly volatile composition during firing. In other words, the lack of tin and high levels of copper meant that creating the colour red could easily misfire. A high degree of wastage made these wares very difficult and extremely costly to produce. A lidded ewer from the same period, although delicate in shape and design, is one example where the firing has gone wrong: the copper has turned grey in some areas rather than achieving the desired red effect.

Comparison between the kendi in question and another underglazed-red decorated kendi from the same period in our collection reveals the great variation in the intensity and richness of the red pigment. Both examples reveal the degree of experimentation brought about by makers using new materials and technologies.

The example with the newly discovered lid is a very fine piece from the reign of the Hongwu emperor (1368 – 98), a period of the Ming dynasty that is celebrated for its high achievements in porcelain production, especially underglazed red wares like this one. It comes as no surprise then, that the object has featured prominently in a great number of books and catalogues, and travelled the world for exhibitions, the latest being a large exhibition at the National Museum of China in 2012/13, titled Passion for Porcelain: Ceramic Masterpieces from the British Museum and V&A.

What was surprising, was the discovery of the accompanying lid that must have been separated from the kendi for decades. The kendi’s record on our Collections Management System had no record of the lid, so we had no idea it had originally come to the museum with one.

The lid was discovered by Serenella Sessini, Collections Move Officer, working on the Blythe House Decant project. She found it in a tray of ceramic fragments from 18th-century England, looked after by our colleagues in the Sculpture, Metalworks, Ceramics, and Glass department. Given that the lid had not been accounted for in our database – the best way to find out whether the two pieces truly belonged together was to try out the fit!

I swiftly jumped on a shuttle bus to bring the lid back from the Blythe House stores to the V&A South Kensington, where the kendi is on display in the top floor ceramics galleries. Lo and behold, just like Cinderella’s shoe, the small lid fit the vessel perfectly!

The practice of fitting Chinese porcelains with metal mounts and lids goes back a long way. Chinese porcelains were far superior in quality and durability to the stonewares and earthenwares produced in Europe. When they entered export markets, metal mounts were added to elevate and protect the objects, as a luxury novelty. The newly recovered metal lid for our kendi served the same purposes: helping to protect the liquid contents, and refine the vessel’s appearance, with its decorative lotus bud.

It wasn’t just European craftsmen who embellished ceramics by making metal mounts, lids, handles, etc, however. In the Middle East, and Southeast Asia, the practice was also widespread.

So, where and when did our kendi receive its metal lid? And what might that tell us about the object’s history?

To answer these questions, a closer look at the object was needed…

In China, Kendi was usually used as a sacrificial instrument in Buddhism. So, what function does Kendi have in Western society? Or a vessel purely as a status symbol?