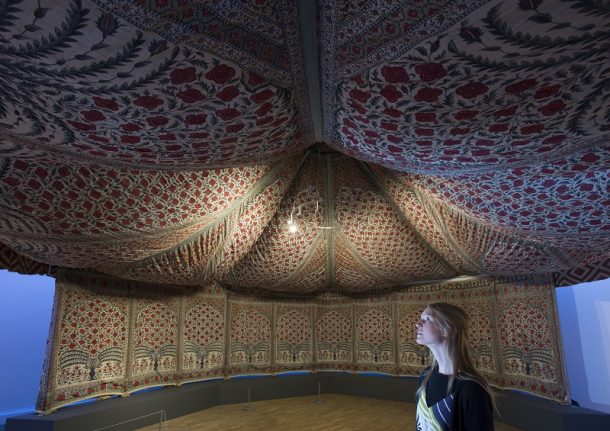

Today’s post focuses on the single biggest challenge of the exhibition – both literally and logistically. Those of you who have already visited the show will have no doubt been bowled-over by the majesty of Tipu’s garden-like tent. But getting its massive canopy up was no small job. To give us a behind-the-scenes look into what it took to raise that roof, we welcome V&A Senior Textile Conservator Elizabeth-Anne Haldane and Technical Services Team Manager Richard Ashbridge, who shared the responsibility of pitching the biggest tent the V&A has ever seen.

Elizabeth-Anne Haldane:

One of the biggest challenges (literally) for The Fabric of India project team was how to display the 18th century tent which once belonged to Tipu Sultan, and is now in the collection of The National Trust at Powis Castle. The tent consists of a separate canopy and walls that would have originally fastened together. Rope latchets around the perimeter of the canopy correspond to leather reinforced sockets at the top of the walls, and the ropes would have been fed through these holes and linked together to securely lock the parts together. The walls are usually on display at Powis Castle with a section of reproduction canopy. However, the actual canopy, which has a 25 metre circumference, had not been displayed since the early 1980s, and its exact shape was something of an unknown quantity. Although the tent canopy still has all its original guy ropes these would not be used to ‘pitch the tent’. Apart from being trip hazards, it would no longer be appropriate to put a tent of this age under such tension, so instead it needed a supportive mount. It was the responsibility of the V&A as the borrower to provide a suitable mounting system.

I first went to view the tent at Powis Castle 18 months before the exhibition opened with Rachel Langley, Senior Textile Conservator from the National Trust and Peter Andrews, a scholar of historic tents. This was an extremely useful visit during which extensive measurements and patterns were taken so that a toile could be fabricated. It was also an opportunity to discuss ideas for the mount, where the object needed support and which original fixings could be used.

The tent would originally have been held up with a large central pole (now lost) which would have been inserted into a leather reinforced opening at the very centre of the canopy. This provided a strong area to suspend the canopy, and the original rope latchets, which were also in good condition, could be used to fasten the perimeter to a mount. Flexible tapes would be used to connect the top to the outer edge, like a giant umbrella structure. These tapes would run along the length of the tent’s original 8 guy ropes to both support and help shape the voluminous tent. The walls, which still have their internal bamboo supports intact, are attached to a timber structure at Powis with Velcro fastening so a similar system was planned for the V&A installation.

The information gathered on this visit was very useful during the design phase of the exhibition and provided a reasonably accurate object footprint to work with. For the actual mount making it was necessary to bring the canopy to the V&A early in order to lay the whole object out flat to determine the exact shape of the outer perimeter, which hadn’t been possible at Powis as there was no room large enough.

Richard Ashbridge:

When we were finally able to lay out the canopy in the V&A’s Raphael gallery one day in June 2015 we (I) had a real sense of what we were dealing with. Although we had access to some academic studies of the tent, these had speculated on the design as it was conceived – not what it had become. We are dealing with a real piece of structural textile perhaps slightly distorted and stretched in places over the 250+ years of its lifetime. Though it was remarkably strong in places with its heavy seams and leather re-enforced sockets, other areas of thinner and fragile cotton would require support.

The tent canopy, once laid out and gently pulled to find its natural form, turned out to have a slightly flattened octagonal shape. Although, to add to the complexity, each of the eight sides is made up of three parts- the angles at these joins were very slight.

The opportunity for much of the project team (curators, designers, technical and conservators) to view the real object was invaluable. Our investigation of the tent helped us see what was needed and confirmed other ideas about the way the tent would be displayed. The main points being:

- It was essential that visitors should be brought under the canopy to see as much of the vivid design as is possible. This might mean raising the tent up higher and supporting the wall section on a plinth to get the fabric safely out of touching distance.

- The canopy would require a central mount to pull the apex of the pitched roof to a carefully judged tension. This would need to be independently adjustable.

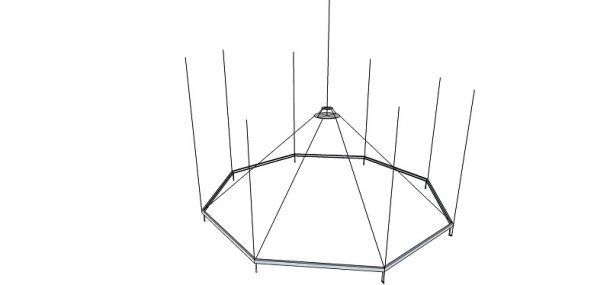

- The tent shape would need to be supported by an octagonal ring which would sit inside the perimeter of the canopy.

- Adjustable strapping would need to run between the inner octagon and the central support to carry some of the canopy weight and support the fabric. This might obscure parts of the tent’s decoration and should be as sympathetic and subtle as possible.

We were also able to get the professional opinions of lighting designers and a rigging company who were able to advise on what would be possible using the current gallery roof and lighting rig in the exhibition court. With different parties chipping in their expertise we were able to sketch out the structure we would require and a way of delivering the competing demands of design, the visitor experience, and preservation of the historic object.

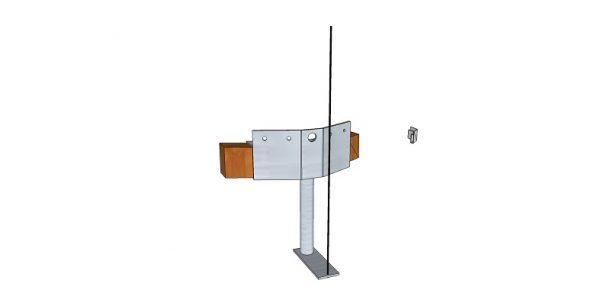

The resulting design required the tent roof to be suspended from 9 hanging points. A padded circular mount would be required for the centre of the tent roof which would need an independent winch to get the tension right. This mount was prototyped in display board before being commissioned in aluminium from a metal fabricators and then padded up in the conservation studio. Two circular rings were required as we also had to accommodate the suspension of a light fitting inside the tent.

The octagonal ring was designed with a bespoke bracket at each of the eight corners. The flattened and slightly irregular octagon shape of the canopy meant that each angle was different. These brackets were made from square tube to accommodate the timber lengths which was used for the sides. This had the benefit of allowing us to adjust the lengths of each side as we installed, to get the tension and shape right.

As the tent roof has hanging fringe each of the brackets required an extended downward arm with a flattened horizontal plate to give us a fixing point to the cables that would hang from the ceiling, our specialist riggers would provide push fitting adjustable wire grips.

The tent roof has a continual series of rope hoops about 20 cm long along its perimeter. These are designed to thread through holes in the top edge of the tent wall. Due to the tent’s age and fragility this attachment method was no longer appropriate. These rope loops were used to thread the tent roof to the octagon support. A perforated rail was attached to the top edge of the support to accommodate these ropes. The walls were erected independent of the roof using Velcro fixings onto a hidden timber framework, which, in turn, is supported by a shallow plinth. This plinth acts as a weighted base to the whole structure.

When it came to installing the tent we were glad of the adjustability we had built into our design. The tent had been templated flat to get the footprint but once we raised the centre mount we started dealing with the tent as a 3D shape. It took a lot of tweaking and adjusting to get the final look of the tent as you see it in the exhibition. The 8 dyed webbing straps which ran from the centre mount to the edge proved invaluable in supporting some of the looser fabric sections and optimising the inner shape of the roof.

Many of the original guy ropes still attached to the tent needed neatly tying up and the shape of the tent walls needed a lot of adjusting to complete the illusion of an inter-connected and erected tent.

Once the final lighting was installed and the base of wall plinths adjusted there was a great sense of achievement. It had been a genuine team effort to bring the spectacle of this wonderfully decorated tent interior back to life.

Our thanks to Unusual Rigging and KPK Sheet Metal for all their contributions.

To read more about the challenges of scale in The Fabric of India check out past blog post Size Matters: Putting on an Exhibition

It is a wonderful work involving a great hard work & planning.Is this tent still available in Albert Museum ?Where the exhibition took place ?

Where is powis Castle? I shall be grateful for this information.Thanks.

F.mallick