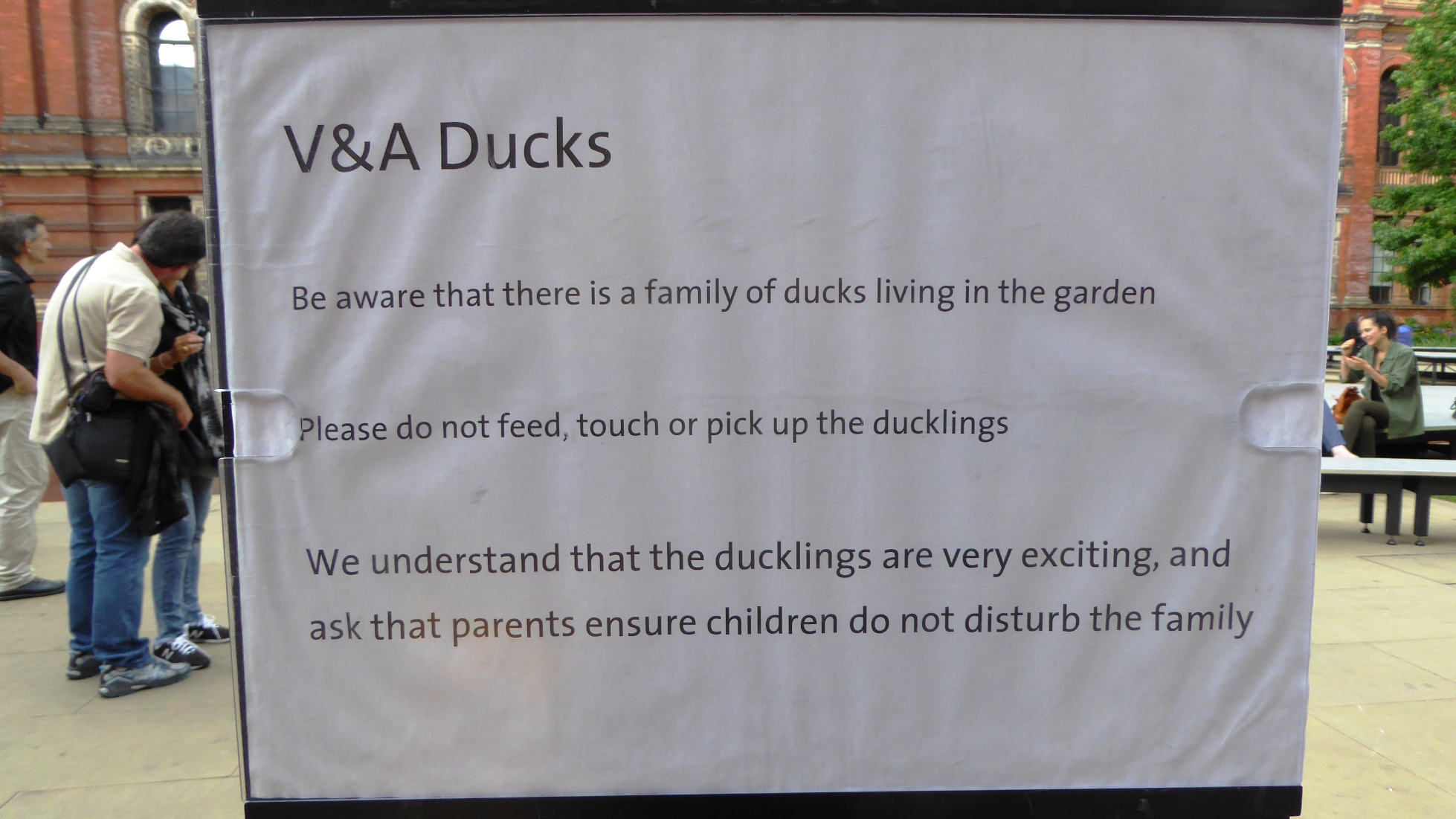

You may or may not be aware that the V&A currently has a family of ducks living in the central courtyard. Mummy duck, Victoria, and her brood of little ducklings are currently attracting more attention than any single object in the V&A (you can watch them dabbling around here) – perhaps rivalling even the exquisitely crafted and spectacular garments in the incredibly popular Alexander McQueen exhibition. Everyone (V&A staff included, many of whom have mysteriously started having a lot of meetings in the garden of late) is crowding round for a peek. These events leave us on the Fabric of India team feeling particularly reassured, since it suggests we may be vindicated…

Last summer, while working with the curators to make the final object selection, those of us on the team who were not so familiar with Indian textiles found ourselves charmed by the recurrence of images from everyday rural life used to decorate the fabrics.

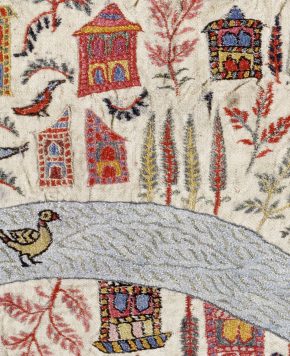

Embroidery, ikat, brocade and print techniques depicted plants, trees, animals, birds – and indeed ducks. It emerged that the team (experts and non-experts alike) displayed a distinct weakness for fabrics featuring ducks – if it had a duck on it, it had a greater chance of making the final cut…

![Ducks [probably] on a length of printed cotton dress fabric, Masulipatam, Andhra Pradesh, 1879. Museum No. IS 1765-1883](https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/121-6-small-ducks_15234219096deb2c5019c96d9f159b52-290x270.jpg)

Of course, I (and doubtless the curators) hasten to add that we did carefully review of all the objects to ensure that they truly illustrated the ideas and stories about handmade Indian textiles we are committed to conveying to the visiting public. Ideas and stories that do not hinge around the presence/appeal of ducks.

With that said… it is very hard to articulate in words what makes the ducks, geese, plants and other animals decorating the handmade textiles of India – or paddling about in the garden – so magnetically appealing.

And while we might at times obsess about justifying our objects selections via the didactic or narrative functions of exhibitions, the mute appeal of the beautiful or charming, or even simply cute, should not to be underestimated. If the museum cannot offer the public the opportunity to access first hand those things which are singular and precious (as both ducklings and handmade Indian textiles most certainly are) it would be missing something that has been central to its purpose since its conception.

We live now in a world where ever more of our functions and desires are fulfilled by interfacing with shiny black boxes – rhythmically swiping and tapping (using as little of our fingertips as possible) to manipulate tiny displays. And while technology seems to give us the ability to do more of what we want, we are also losing something. Writers such as Jaron Lanier and Nicholas Carr have written insightfully on the disconnection of our interactions from the material realm, and their elevation into a non-tangible digital realm. By extension, as more and more of the tools with which we achieve what we need to do day to day come to resemble shiny black boxes, there is a reduction of variety in our tactile landscape.

Museums are not immune to the effects of this. They too embrace digital media and content, often with the ambition of ‘bringing the visitor closer’ to the museum objects that they can’t touch – whether through more content or more context. But on the other hand, the devaluation of the tangible in favour of the digital in life outside the museum may pose a threat to the very relevance of museums in contemporary life. After all: why look at mute material objects when you can interact with digital interfaces?

Museums should not be complacent in dismissing the impact on their purpose of this wider move toward the digital. However, the popularity of the Victoria and her ducklings shows us that the appeal of things we can touch, accessing unmediated by any technologies, can and will distract any number of people from their glorious gadgets.

This tactile desirability is a quality shared by both the ducklings and handmade textiles from India. Textiles from India are made in a huge range of materials and degrees of fineness. I particularly like the less fine fabrics since they bear the irregularities of being hand-woven overtly; you sense you are touching both the raw materials and the work taken to transform them into fabric.

Museums, for obvious reasons, by necessity must try to convey materiality through ‘look’, not ‘touch’. Like many of the rare and precious things in the museum, people (myself included) desperately want to touch the ducklings – to see what their fluffy little feathers feel like. But, like all things in the museum that people want to touch, for their safety our visitor services staff are doing everything they can to stop the visitors from stroking, poking and pursuing them.

Try as we might, with whatever incredible technologies now exist, there is little that can replace the experience of actually feeling something. So for The Fabric of India, we are currently designing a table of handling samples especially for visitors to touch – offering a variety of handmade fabrics that we are currently shipping from India. We hope that this tactile interaction will allow visitors to better understand the skill and work involved in producing handmade textiles, and appreciate those fragile and precious textiles behind glass that cannot be so experienced.

As much of life turns digital, museums have the opportunity to be places that remind us of the satisfaction and joys of both our own materiality and that of the world around us. And, whilst we ask you not to stroke the ducklings as it distresses them, in the autumn we will be welcoming you to come and touch some of the amazing handmade textiles of India.

This article had my family in stitches over breakfast, and excited our minds, seamlessly, with such a vibrant yearning for ducklings and Indian textiles, intertwined; I am now drawn to waddle from my laptop and investigate the museum, real-time, duly, with all my family in toe.

Those ducklings and their mum were so, so cute dashing about the V & A garden and the Fabric of India exhibition is going to be incredible. Rosie’s blog brings both together beautifully.