In 1971 three black inmates of Louisiana State Penitentiary (Angola Prison) in the United States established a chapter of the Black Panther Party inside the prison. They subsequently served extraordinary periods of continuous solitary confinement – over 100 years between them – and became known as the ‘Angola 3’. Robert King was released in 2001. Herman Wallace died in 2013 after 41 years in solitary, a few days after his conviction had been overturned and the judge ordered his immediate release. Albert Woodfox remains in prison, despite demands for his release by Amnesty International and other campaign groups and the fact that his conviction has been overturned three times. You can read more about their story here.

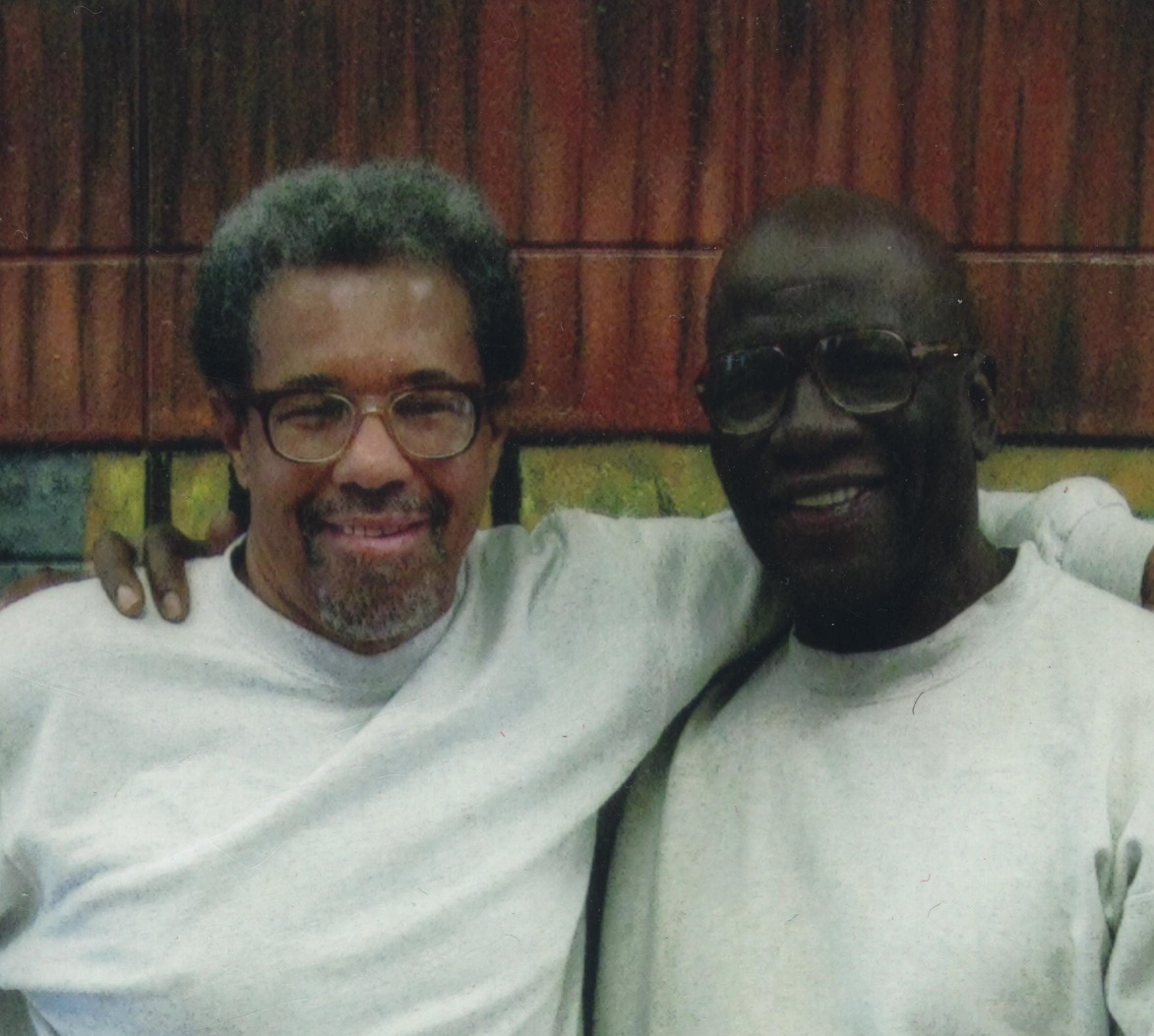

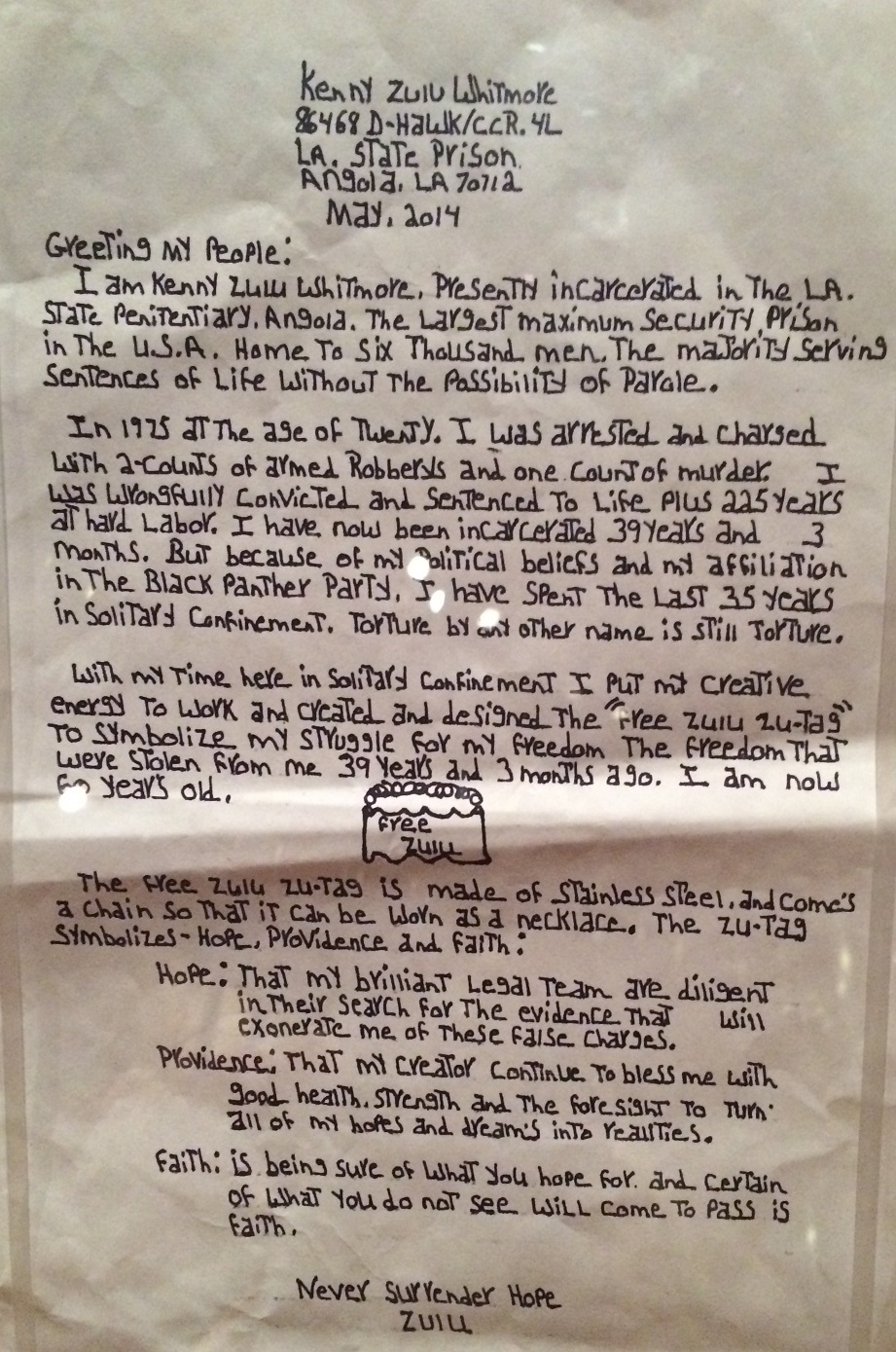

Also still in solitary confinement in Angola Prison (for over 35 years) is Kenny Zulu Whitmore who joined the Black Panther Party when he met the Angola 3 and became politicised. From his cell he encourages others in their political struggles, and through letter-writing he has gained friends all over the world. He designs pendants which are handcrafted by other prisoners from basic materials and sold to generate funds for his legal campaign. One is displayed in the Disobedient Objects exhibition alongside a letter he has written to V&A visitors explaining his situation. You can read the letter at the end of this blog post. Zulu’s address is included if you want to write back.

In this guest post A’level student Poppy Newell Richards recalls her experience of visiting two members of the Angola 3 in prison when she was 11 years old.

I think that there is something significant about the innocence of a child. Being only 11 at the time, when I stepped into the visiting room of Louisiana State Penitentiary and ran up to Herman Wallace to give him a hug I was completely unaware of how strange this must have been to everyone else in the room. It was only a long time afterward that I realised. A white, 11 year old girl running into the arms of a convicted murderer, a peculiar sight to the other inmates, their families and prison guards alike. Yet I was unable to see it that way, I was not familiar with the prejudice’s and injustices of race and class that I now see very frequently. I saw both Herman and Albert as people, not criminals. It never once struck me that I was in a dangerous place, surrounded by dangerous people, despite the fact I was sitting in one of the most notorious prisons in the whole of the United States.

I still remember how I felt looking around that room. It was a feeling of intense curiosity and sadness. I felt as though I could physically feel the injustice. About a hundred men, in identical clothes, sitting with there loved ones whilst bound by shackles at their feet. I was too young to understand how it could ever be justified and widely agreed upon to deny people of their freedom; to take away even the simplest pleasures, like taking a walk or a hug from a friend.

Despite this however, I did in no way find the visit traumatic. I asked Herman and Albert questions about their daily life, what was the food like? How long did they spend in their cells each day? I tried to imagine being contained 23 hours a day, constricted to a limited few occasional activities, and being served just about edible food onto the cell floor. Of course it was impossible, it was completely unimaginable to me, just as it is to most people. I felt a huge amount of empathy towards them, but now being older, I have a huge admiration for their plight. They have shown me just how much strength it takes to keep your faith, despite the enormous temptation to give up and loose hope. They also showed me what it means to take your freedom, however limited it may be, and keep fighting for justice, not just for yourself but also for others, until the very end.

Even after Herman Wallace’s passing, the lessons he has taught me will always remain. They have helped to shape my character, built my spirit and to always believe in the power of love. Just knowing of Herman and Albert’s struggle has given me strength, and a sense of duty to never give up on the struggle for justice. The Angola 3 are not the first innocent people to suffer injustice at the hands of the state, nor will they be the last; but I truly believe that this battle can be won. There is no competitor to the power of the people, and one day I hope to see a fairer world, where the rights of all people are always afforded to them, with no restrictions. We have a long way to go, but it is always possible. I will always take comfort in knowing that my friends, Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox will leave this world exactly how they entered it, Innocent and Free.

Pendants designed by Zulu are available here

Listen to a recording if Herman Wallace reading his poem

Poppy Newell-Richards

HI, i am from argentina, well, voy a escribir en español, me gustaria saber mas la historia de este señor pero de ser posible, si me la envian a mi correo en .pdf y porque ha ocurrido lo ocurrido.