On the day he launched The Life of Pablo, Kanye West’s label, Def Jam, announced, ‘in the months to come, Kanye will release new updates, new versions, and new iterations of the album’. Like him or loathe him, Kanye was the first major artist to publicly announce he was releasing an unfinished record and in the months after launch he included an additional song and added vocals to a track that he’d previously stripped out.

Until the last couple of years, if an album was launched and an artist had reservations about some of the tracks, it was tough luck. Artists from David Bowie to Nirvana have famously distanced themselves and even outrightly criticised some of their previous albums. But the music industry is changing. Now, an album launch doesn’t necessarily mark the end of a period of intense work, but rather the beginning.

It is, after all, so much easier in the digital age to experiment, adapt and iterate. So could this (in Kanye’s words) more ‘innovative, continuous process’ be applied to the world of exhibition development?

An exhibition (at the V&A at least) is typically three years in the making. Whereas a digital product can take a matter of months, sometimes just weeks to launch. That’s because these days – from the music industry to museums – most digital development follows an Agile approach, with a focus on launching early with a minimum viable product, or MVP. The launch of a digital product is just the beginning, rather than the finale.

So, could the exhibition development process follow suit, and use a more Agile approach? And might this approach help us create even better exhibitions and museum experiences?

A minimum viable product

A minimum viable product is the smallest thing you can create that delivers value – for users and for the business. By getting a small version of the product out soon, it’s clearer much earlier on in the process whether you’re on the right track before putting a large amount of time and resource behind a product. By putting it into the hands of your users as soon as possible, you can change tack if needs be.

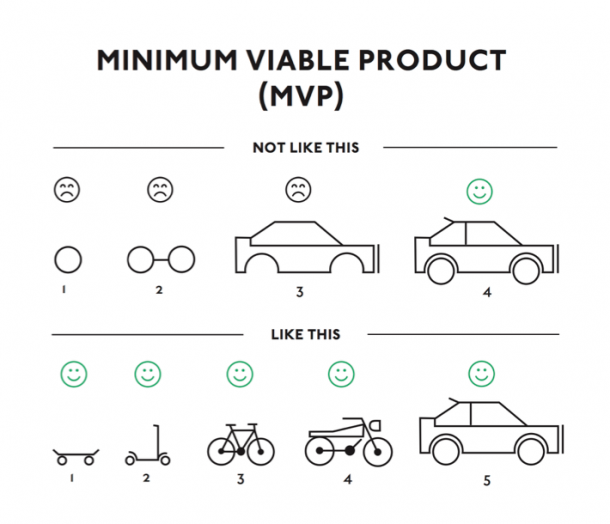

I’ve used the illustration below before, because it’s a good way of explaining the difference between a traditional waterfall model and an Agile approach. In building a car, a typical waterfall project management process would involve building wheels, chasis and so on. Agile, on the other hand, frames the product around the job to be done. If that job is ‘to get from A to B’ then there are simpler ways achieve this goal than building a car. Instead you might construct a skateboard, a far easier way to deliver this user goal quickly.

What can we learn from Agile?

Most museum processes follow a waterfall approach. And there is good reason for that. It makes sense within a building project, for example, for walls to be built before windows are installed. Exhibition development also follows a waterfall approach and, typically, takes place over several years. A generous timeline is considered the best way of delivering a quality exhibition and a suite of associated products and activity, from the exhibition publication to the merchandise and marketing campaign.

All this activity culminates in the exhibition launch, an exciting moment where, finally, you get to hear what your audiences think. And, if the reviews are good, and word of mouth is strong, the audiences will come. But what if that’s not the case, and audience numbers are low? Do you overhaul the marketing campaign? Or the exhibition itself? The former does happen, but it’s still rare that an exhibition changes post opening because of visitor feedback.

This is where other museum processes, including exhibition development, might learn from the Agile approach used in software development. Could the exhibition launch be just a starting point for developing an experience that works best for the audience? Could an exhibition begin with a small number of objects, perhaps even just one? Should we think less about MVPs and more about MVEs, or minimum viable experiences?

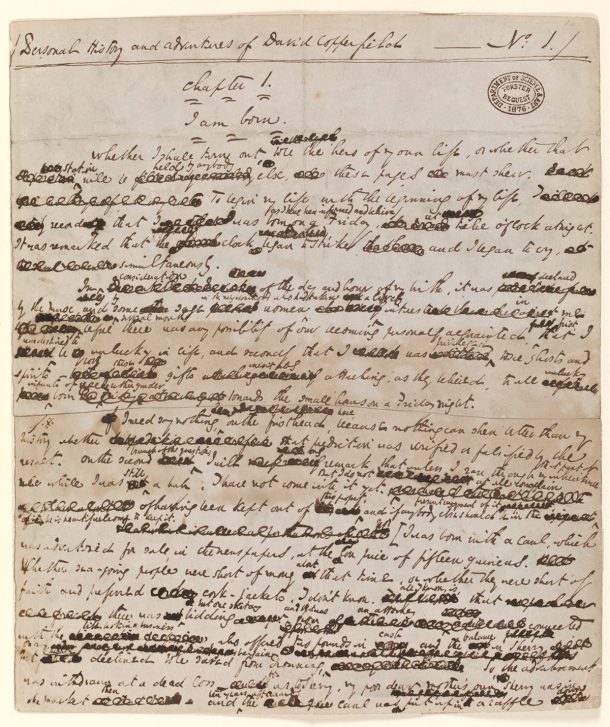

These are some of the questions we are mulling in our Immersive Dickens project, our AHRC funded research into ‘next generation immersive experience’ in which we are using an Agile process to prototype a mixed reality experience for young people. We are working with immersive theatre pioneers Punchdrunk Enrichment and creative technology studio The Workers to bring an original Charles Dickens manuscript to life through an innovative mix of technology, performance and curatorial practice.

Unlike the typical exhibition process, we are developing a prototype experience within nine months around one museum object. In so doing, we hope to deliver a minimum viable experience. Our hope is that this prototype will become a more fully developed display or exhibition. Our prototype takes a very different approach to traditional exhibition development, by drawing from three core aspects of Agile – starting small, iterating and improving, and involving your users.

Starting small

Instead of involving several hundred objects, our prototype experience will involve just one object, an original manuscript by Charles Dickens. The manuscript, complete with errors, revisions and deletions, gives an incredible insight into the creative process of one of Britain’s most loved writers.

We believe that by distilling the exhibition experience down to just one object, we will be better able to focus on the core experience. We like the idea of an exhibition that launches with just one object. An exhibition that keeps a determined focus on doing one thing well. An exhibition that could be augmented and extended with further objects to help illustrate the story over time.

Iterating and improving

The manuscript itself shows Dickens’s creative process as a highly iterative practice. So too, the development of our prototype experience has been highly iterative. We developed a narrative and a user journey for our experience, and have incorporated audience feedback to improve them. This, we hope, will ensure that the MVE delivers on our on user goal – for students to get a better insight into the creative genius of Charles Dickens.

When we launch the prototype in October, we hope that this will mark just the beginning of this experience. We will change and improve the MVE based on further feedback, both qualitative and quantitative, from our audience testing.

Using data to change and improve what you’re doing is not a new concept in digital development. But it is new for exhibition development. This idea is touched on in The Digital Museum, a conversation between the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s chief digital officer Loic Tallon and NEW INC director Julia Kaganskiy:

“Imagine: an exhibition in which the museum surveys visitors every day and makes one incremental change each night to hone the exhibition design. The exhibition would be “more perfect” on closing day than opening day.”

Loic Tallon, chief digital officer, Metropolitan Museum of Art

It is an exciting thought that this might one day become regular practice for exhibition development. But it will involve considerable cultural change within our institutions. We hope that this prototype might point to ways a more iterative development process might increasingly become the norm. Ultimately, of course, we will be de-risking the exhibition development process by continually iterating and improving the exhibition offer.

Involving your users

Agile, like any good design practice, draws from a human-centred design process. The basic premise is that involving your users (audiences) in the design process will result in a better product, service or experience. In all our work in designing and developing digital products for the V&A, we always strive to take a human-centred approach. We conduct user research to test our assumptions and understand user needs. And we run user testing to help refine digital products and ensure they are usable and – hopefully – delightful too. (Read Choosing the Right Yardstick on the different human-centred research tools and methods we use at the V&A.)

Human-centred design, at its simplest, involves consulting the potential users of your product. Participatory design goes a step further. Its focus is not simply on the end product, but in participants gaining an insight into and helping to shape the design process.

As part of our Immersive Dickens project we ran a series of participatory design workshops with students from across the UK. These workshops aimed to give students an understanding of how immersive experiences are developed. The students were a vital part of the design process of developing an immersive experience around a Dickens manuscript. The ideas they generated in the workshop shaped the narrative and format of the prototype experience.

Working in digital media in the museum sector can be as challenging as it is rewarding. All the more so if you’re using an Agile approach to digital development. It is hard to think of an approach more at odds with the traditionally waterfall processes within the museum. Despite that, digital teams in museums have embraced Agile over the last decade or so, to considerable success. But could other teams, particularly those involved in the exhibition process, use Agile too? Might we deliver better, more audience focussed exhibitions and experiences as a result? We hope that our Immersive Dickens project will show how.

Great read! Love the idea of an iterative exhibition, changing and evolving from an MVP to something that is responsive to visitor needs and wants in real time.

Also like the music analogy. Interestingly, I think Beck may have beat Kanye to the punch on this one with his song reader album in 2012; rather than releasing an album of recorded music, it was in the form of sheet music ready to see what other musicians/users would do with it! https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Song_Reader