This is a special guest post by design writer Kristina Rapacki. Kristina is the deputy editor of Disegno, and writes about a range of topics, from animal architecture to interface design.

“How do you bring people together when you can’t bring people together?” asks Jenny Elliott, an urban designer and landscape architect based in Edinburgh. Hopscotch, she thought at the beginning of lockdown, might be one way.

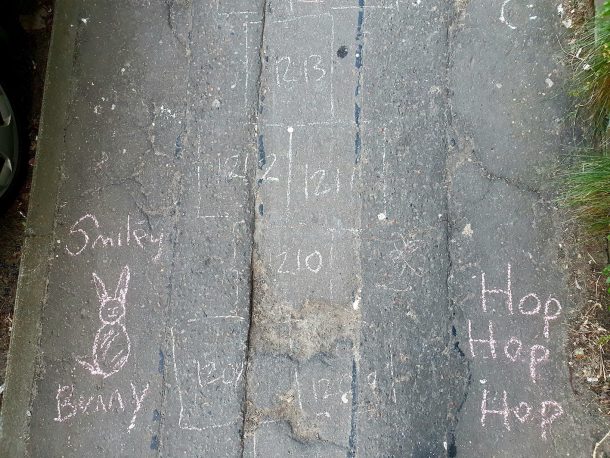

Elliott drew up a few squares on the pavement outside her home, left a box of chalk there, and put up a hand-written sign. “Please take a chalk … for … HOPSCOTCH!” it read, and then posed a challenge: “Add some squares to the hopscotch on your walk up the hill, and see if we can make it to the top (Bruntsfield Place) before it rains.”

It didn’t rain for another two weeks, and the hopscotch court grew, by collective effort, into a 400m grid comprising some 1,400 squares. It reached the top of the hill, and even peeled off in other directions before being washed away by rainfall. Elliott had to move her sign further up the road several times to keep up with the design, but “the biggest challenge,” she says, “was trying to source enough chalk. All the neighbours chipped in, and any chalk at the back of their cupboards came out.”

As the world went into lockdown this spring, many cities saw their pavements and streets slowly transformed by chalk drawings. Hopscotch, in particular, was a popular motif combining creative chalking with play. A home security camera in Irvine, California, caught an Amazon delivery worker hopscotching back to his van after dropping off a parcel. (Heart-warming? Yes. Extremely creepy how the video was captured? Also yes.) Clips of refuse collectors hopscotching down streets while picking up bin bags in Hull, Darlington, and Derbyshire circulated on local news websites in March and April. Hopscotch, it seemed, was as popular among children as it was among the key workers who encountered it on their shifts.

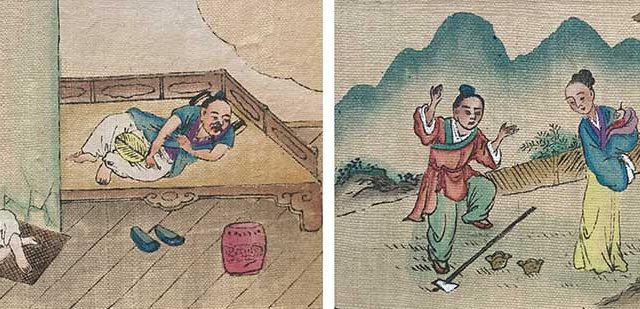

Hopscotch is an ancient game believed to have originated in prehistoric India. A game of its description is included on the sixth- or fifth-century BCE list of games prohibited by the Buddha, a list which also features board, dice, and ball games, as well as the curious game of ‘guessing a friend’s thoughts’. In England, it was first recorded by Francis Willughby in the seventeenth-century Book of Games, referred to there as ‘scotch-hoppers.’

A common hopscotch court design is the eight-square: a numbered grid of alternating single and double squares through which players hop on either one or both feet, careful not to tread on any lines. Additionally, a ‘marker’ or ‘lucky’ – often a pebble or bottle cap – is thrown onto the court, with players having to avoid the square on which it falls. But there are many ways of playing hopscotch, and many court designs. Variations of it exist all over the world, and go by different names: the German Hinkspiel, Igbo swehi, French escargot (played on a spiral court), Hindi Kith-Kith, Bengali Ekhaat Duhaat, Swedish hoppa hage, Persian Laylay, to name only a few.

Hopscotch teaches counting and co-ordination, and can be played while observing physical distancing rules. As such, it has made its way onto new lists: Covid-era ones, itemising the kinds of activities parents should encourage their kids to do while self-isolating. “Put the phones and tablets down and grab some coloured chalk for some outdoor fun on your driveway!” writes The Scotsman.

But unless you have a driveway or a private garden with paving in it, such advice is not, well, advisable. In the United Kingdom, at least, you mustn’t draw on public streets without permission from your local council (usually granted in the form of a ‘play street’ permit), even if it’s with chalk. This has been widely flouted and loosely enforced, of course, especially during lockdown. But in 2013, a 10-year-old girl in Kent was threatened with criminal damages by an over-zealous police officer for chalking a hopscotch court outside her home. More recently, last month, a local inspector at a housing estate in Bishopsbriggs, Dunbartonshire, told parents that their children must “refrain from [playing hopscotch] immediately,” arguing that the chalk courts ruined the overall appearance of the property. An apology was later made, and the instruction rescinded.

Why should it be so transgressive to chalk up a play area in public space? Jenny Elliott, who initiated the Edinburgh hopscotch, thinks the game has an inherent mark-making appeal. “That’s the delight of drawing your own hopscotch as a child,” she says. “You’re often drawing it somewhere that you’re not normally allowed to draw in. But it’s alright because it will wash away.” As an urban designer, she finds this impulse important. “It gives you some control over your surroundings as a citizen. I think a lot of people don’t feel they have that ability to shape the way their outside environment looks and feels.”

Perhaps that’s no wonder, given the dominance granted to cars on our streets; the permits required for play; and the threats of mean-spirited property inspectors like the one in Bishopsbriggs. But Elliott’s initiative shows that when given the opportunity, people of all ages delight in shaping the look and feel of their immediate surroundings. “We had people personalising their own squares,” she explains. “When we got to 1,000, somebody did this huge drawing around it.” Participants dedicated squares to NHS staff and other key workers, and wrote birthday messages for local children. The design of the court was also creatively adapted to fit around and respond to urban features along the road: “There was a small laneway that cuts across the street,” Elliott says, “so somebody drew a rocket ship to ‘help’ the hopscotch over.”

As lockdown restrictions begin to ease, traffic levels have picked up again. And although hopscotch courts are normally drawn on pavements, not the road itself, the constant presence of cars makes it less likely for parents to want their children out playing in the urban environment. With a brief interlude of a few months, we are back to the trajectory mapped out in a 2007 report from Play England: it found that while 71 per cent of adults remember playing out on the street as children, only 21 per cent of children in 2007 actually did so.

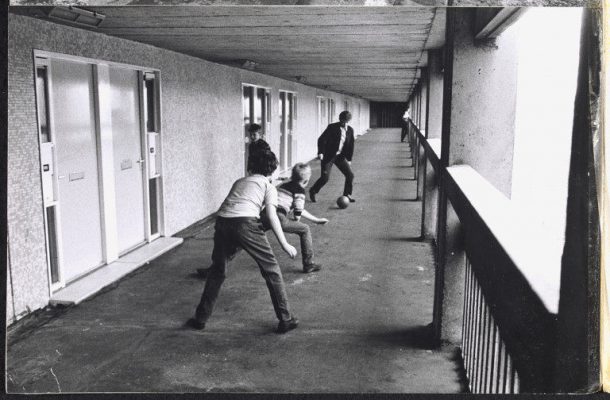

Architects and urban designers have long stressed the importance of spontaneous play in towns and cities. It was no coincidence that, as personal cars became increasingly present on our streets, some of the most powerful design ideas for play emerged in the postwar decades. The 1960s was even host to the so-called ‘playground revolution’, as well as, of course, other revolutions. This was the time of Dutch architect Aldo van Eyck’s Amsterdam playgrounds: hundreds of spaces developed in squares, parks, and vacant lots, all featuring minimalist equipment which could be played with creatively. (Sadly, only 17 of these playgrounds remain.) In Britain, civil engineer Colin Buchanan’s 1963 Traffic in Towns report led to increased pressure to establish ‘home zones’ or permanent play streets, where traffic was heavily reduced in favour of pedestrians, cyclists and playing children. And architects Peter and Alison Smithson championed the concept of ‘streets in the sky’, traffic-free walkways in high-rises which could be used communally by residents. (That this typology didn’t always live up to the Smithsons’ vision is another story.)

Many of us regret seeing cars return in great numbers to our streets. At the beginning of June, air pollution was reported to have risen back to pre-pandemic levels in China after a significant dip during its lockdown measures, and European countries are expected to follow. While some cities have vowed to pedestrianise more streets and offer pop-up bike lanes for commuters returning to work, it is too soon to say what the long-term effect this period will have on the ways we use our streets. “It’s ultimately a choice,” says Elliott. “Do we want cars to dominate these spaces? Or do we want to give them over to other uses? Or is there a balance that can be struck?”

Related Objects from the Collections:

The photographs of Roger Mayne

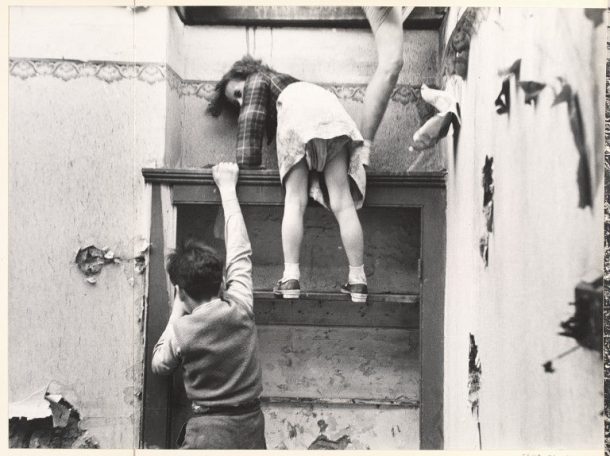

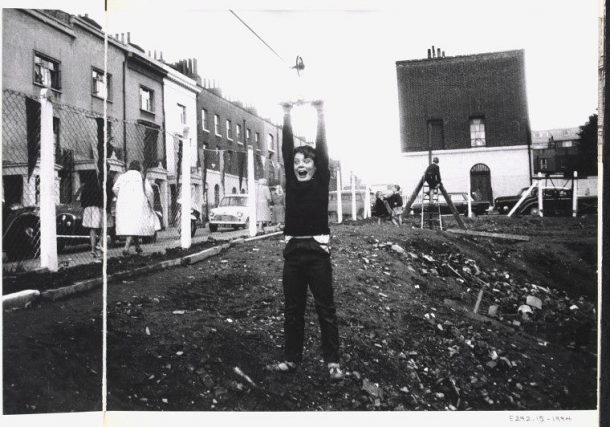

Roger Mayne spent much of the 1950s and 60s documenting urban Britain, with a particular focus on lower-income neighbourhoods. Because of the cramped living conditions inside of flats, much of the daily life of these areas took place out on the streets, which at the time were still relatively unencumbered by car parking and vehicular traffic. His photographs show how children employed incredible inventiveness in turning the streets and the objects around into elements of play.

‘Derelict houses with children playing’

‘Clarendon Crescent, Paddington, 1957’

‘Hyde Park Estate, Sheffield, August 1966 [boys playing with ball]’

‘Adventure playground, Islington, August 1963 [boy on rope]’

Further reading:

Juliet Kinchin and Aidan O’Connor (eds.) Century of the Child: Growing by Design, 1900-2000, Museum of Modern Art, 2012.

‘How architects have tried to create “streets in the sky”’, Edwin Heathcote, Financial Times, 5 May 2017.

‘Giant hopscotch game with nearly 1,400 squares reaches end of 400m long Edinburgh street after several days of sunshine’, Jamie McKenzie, Edinburgh Evening News, 25 April 2020.

‘Hopscotch chalk ban overturned after outcry from parents’, BBC News, 20 May 2020.

‘Aldo van Eyck’s Playgrounds: Aesthetics, Affordances, and Creativity’, Rob Withagen and Simone R. Caljouw, Frontiers in Psychology, 4 July 2017.

Fascinating article, thanks Kristina. This resonates with one of the issues covered in the excellent exhibition on play recently held at Wellcome Collection.

A general request (as I’ve seen it on other people’s posts here) – please do not add links to pay-to-view articles.

Hello,

I live on the street featured in this article. Soon after the hopscotch was created, I made an illustration of the street, turned it into prints then gave everyone on Leamington Terrace a copy. It was a wonderful thing for Jenny to do. This project has created a great community spirit. When before we would hardly nod to the people on the street we didn’t know well, we now stop and have a chat. I feel very lucky to be here.

Here is a link to the print should you wish to see it:

https://www.cassandraharrison.co.uk/products/lockdown-hopscotch-leamington-terrace

Bonjour,

En Français (du moins à Paris, dans mon enfance) nous disons la marelle, et non pas l’escargot (belge ?)