The barricade is an object steeped in urban history. Whether deployed as an act of bottom-up resistance, top-down control, or more recently as a preventative measure against terrorist acts, uniting these differing motives is always the vague association with potential and past violence. More recently, ad-hoc and temporary barriers have been deployed in cities around the world, to either ward off use of public spaces or dissuade vehicle use on certain streets.

The photographer Shashank Peshawaria kindly shared a series of photographs with me a few weeks ago documenting his city of Amritsar, India after curfew was imposed in the state of Punjab. In his words: “The barriers are meant to curtail vehicular movement, which is only partially permitted in the morning hours from 7am to 11am (these timings change frequently) for people to access essential items and services. At these times, very few barriers are momentarily removed while most remain fixed. The barriers are also supposed to keep people within their localities.”

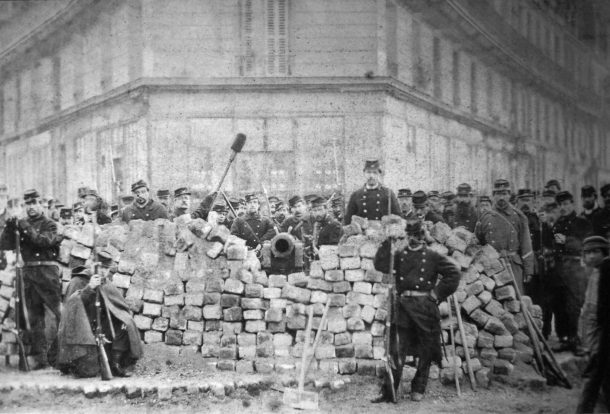

The improvisatory nature of these are a far cry from the type of heavily-engineered permanent steel barriers in European cities we’ve seen installed following a spate of van-related terrorist attacks over the last few years. Instead, it hearkens to more grassroots events, in which revolutionaries and protestors were forced to work with the materials at hand: most notably in Paris, in 1871 where paving stones were ripped up to form barricades during the Paris Commune, and similarly a century later during the 1968 protests which gave birth to the phrase “Sous les pavés, la plage!” as paving stones were commonly laid on a bed of sand. The irony here of course, is that Peshawaria’s photographs do not reflect some revolutionary impulse, but a state stretched thin to react quickly to a crisis, and so deploying whatever means necessary.

The photographs reflect a recurring thread we’ve seen play out in several different ways: lacking resources, people are forced to work with the objects at hand to find solutions. But perhaps the most interesting point here is the latent potential of any object on the street to be turned into an organizing force. Trash cans, parked cars, paving stones – these all form a material library of potential use, whether for control, or critique, but also for other explorations of how we organize space.

Gradually in London, there’s been a growing accumulation of things strewn on the street and in our public spaces. Discarded mattresses, chairs, unwanted books and toys. City streets under lockdown are suddenly a bit messier, filling with the detritus of everyday life. Sometimes these objects are toyed with or repositioned to different effect. A mattress propped against stump, recalls the casual genius of an Erwin Wurm one-minute sculpture. Household chairs taken outside for the very first time become new points of socializing. Indeed, any object when taken out of its natural habitat can be redeployed, a material from which to create new conditions. Rather than see these objects simply as a way to recreate the violence of the barricade, they can help us reimagine what a street might be and what being out in public means.

Further Reading:

‘Chinese villages build barricades to keep coronavirus at bay’, Don Weinland and Sun Yu, 7 February 2020.

‘Europe Barricades Borders to Slow Coronavirus’, Matina Stevis-Gridneff and Richard Pérez-Peña, New York Times, 17 March 2020.

‘Armed vigilantes use tree to barricade man in his home because of New Jersey plates’, James Crump,The Independent, 30 March 2020.

‘Aylesford woman barricades house amid social distancing fears’, Rebecca Tuffin, KentOnline, 11 April 2020.

Related objects from the collections:

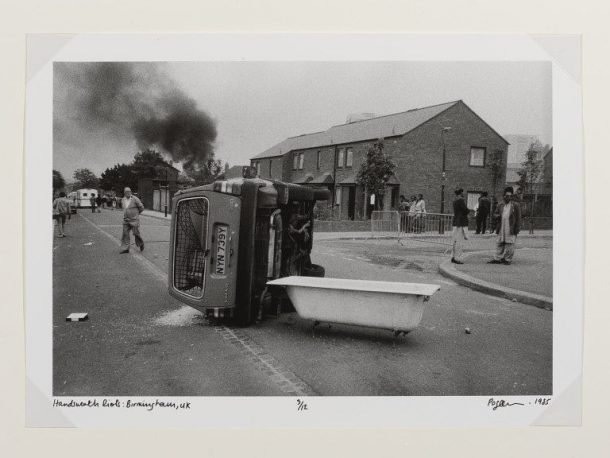

Handsworth Riots (photograph), 1985

During the 1985 Handsworth Riots, Pogus Caesar took his 35mm Auto Focus camera to the streets to document what was transpiring in the local community. Many of his photographs are marked by the surreal juxtaposition of objects which had taken on strange new configurations out in the public, such as here where a bathtub collides with an overturned Central TV news car.

E.1203-2012

These architectural spikes are meant to be applied to surfaces to deter the homeless from sleeping or temporarily using a space for rest. The proliferation of anti-homeless design measures, such as these, installed in cities around the world, is a reminder of the exclusionary role design can play in creating public spaces, acting more as a barrier than an invitation to participate.

CD.50:1 to 20-2014