Co-authored by Livia Turnbull and Maude Willaerts, Assistant Curators on the Design 1900 – Now galleries.

The Design 1900 – Now gallery opened on 17 June 2021 (you can read more about the opening here). The displays reveal a bold new curatorial narrative through over 250 designed objects, around 50 of which are new acquisitions. Adding to the V&A collection is an exciting process requiring patience, resourcefulness and a lot of thinking – but how is it done?

What is an acquisition?

An acquisition is a new addition to a museum collection, which is recorded, preserved and made accessible for future generations to enjoy and learn from. We collect in the here and now – contemporary history in the making and seek to address gaps and omissions in the existing collections.

A needle in a haystack

Curators are responsible for shaping our collections, but it’s not exactly a shopping spree!

Acquisitions are driven by expertise and an understanding of specific fields of design for which the V&A is responsible. At the same time, they are often prompted by the needs of a specific project, and new galleries, exhibitions and publications often necessitate expanding our holdings. In Design 1900 – Now, we aim to tell a story of design and society that is broad, international and inclusive. Our wish list was composed of 20th century and contemporary design examples reflecting our globalised world, whilst paying attention to questions of representation. If the first step is to research desirable objects, the next one is to study the feasibility of an acquisition. It’s not a decision that we take lightly: once an object has been formally acquired, the museum becomes responsible for its storage, care and preservation indefinitely, and it is very difficult for the museum to dispose of any collection objects. This latter process, called deaccessioning, is paperwork-heavy and time consuming.

It’s therefore important to think of acquisitions beyond the needs of a specific project and to carefully consider which objects will remain relevant for generations to come.

Who do we approach?

After finalising the objects selection, it is time to focus on how to source it. Objects entering the collection are purchased, commissioned or gifted. They can be sourced from a myriad of places, from specialised dealers to designers, companies, organisations or individuals.

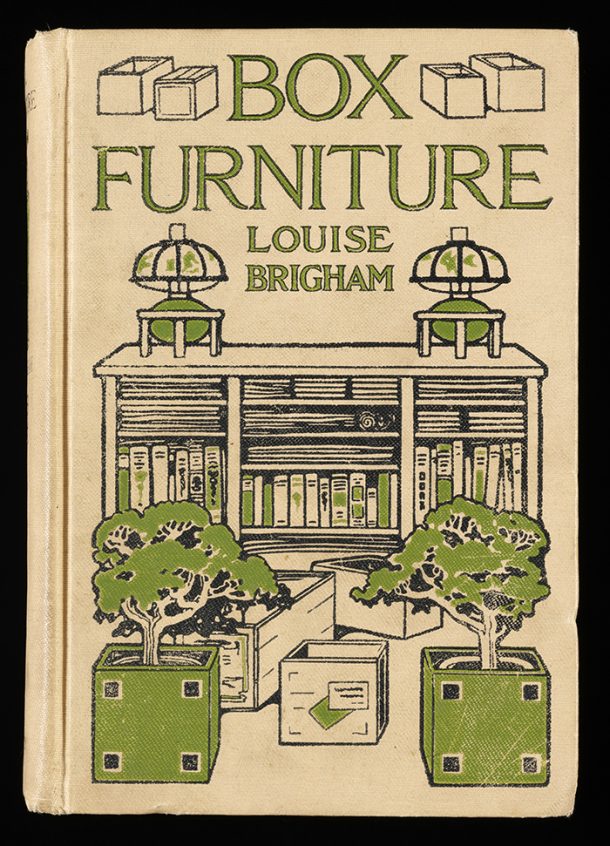

Some purchases are made in a click: we bought a Lampan table light directly from the IKEA website, and a 7-Up can radio from eBay! Others, such as a first edition of ‘Box Furniture’ by designer Louise Brigham, are the result of a months-long hunt on second-hand online bookshops.

The museum is also extremely lucky to benefit from the gifts of generous donors. We have acquired the Akuaba chair from designer Huren Marsh after he reached out to us to find a permanent home for the chair he designed as part of his undergraduate degree. An avid collector of 20th-century design gifted us a Cosmolux sun lamp designed by Dieter Rams in 1964, and the company Herman Miller donated a prototype of their unreleased Aeron Live OS chair.

While researching potential acquisitions for the Design 1900 – Now project, we came across designer Daniel Quasar’s Progress Pride Flag, an inclusive redesign of Gilbert Baker’s 1978 flag. Unfortunately, when we got to it, the flag had already sold out. But what happens when an object like this is not available? We commission it! The designer went on to produce a bespoke appliqué version of the flag. This is where we are very lucky.

Paperwork galore

Once we are certain that we would like to acquire an object and have considered the options for gifts or funding, we start an acquisitions procedure on our Collection Management System, MuseumIndex+ (CMS). The programme guides us through all the necessary documentation. It also prompts us to start some of the key procedures including Due Diligence, identifying image rights, and writing a justification (more on these below).

At the same time, we start a Registered File, where we store the paper versions of all the essential documentation, legal paperwork and correspondence. It’s not exactly glamourous – but it’s an essential part of the work we do. And we know researchers of the future will be poring over it to gain that extra, first-hand insight.

Show your credentials

When an object enters the collection, we need to investigate its history.

A series of checks, known as Due Diligence help us establish whether the owner can demonstrate ‘good title’ to the object, or whether it has been stolen and/or linked to illegal trade. We will not acquire the object if we find evidence for any of this. Fortunately this is rarely the case, and this legal process helps us to uncover the history of the object. When checking the provenance of the Akuaba chair, Huren Marsh told us that his design was part of an exhibition titled “Design at Kingston: Work by students of the School of Three-Dimensional Design at Kingston Polytechnic”, shown at the V&A in 1984. We were thrilled to discover that beyond collecting a very interesting design, we also collected a piece of the museum’s history.

We also check an object’s materials to understand if they are derived from endangered species of plants or animals. This is often done together with our colleagues in our Conservation department. They are materials experts and well able to guide us through this process of identification. The trade of materials from endangered species is controlled under the Convention for the International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES). If such materials are found, we have to acquire a CITES licence to import or export it. Fortunately, we did not come across anything like this when acquiring for Design 1900 – Now.

We keep copies of documentary evidence, correspondence and research notes on CMS, and in the object’s Registered File.

Writing a justification

This is one of the most exciting parts of acquiring as we get to relish in research, and write about the object. The justification will cover topics such as the background of the designer and the history of its maker or manufacturer, contextualise the creation of the object and explain its historical significance, innovative uses or user-made modifications, as well as detail its design and the materials and techniques used. The second part of the justification focuses on explaining why this object is a good fit for the collection, how it complements other objects in the collection or fills a gap and fulfils some of the collecting priorities.

To suggest an object for acquisition, we must write a proposal to be reviewed by peers and the Keeper (head of curatorial department) of the acquiring collection. Acquisitions which meet certain criteria of financial or cultural value, significance or funding sources must be proposed to the Collections Group, which gathers senior staff to discuss the merits of the acquisition and allocation of funds.

Copyright

It is important to clarify which rights cover a newly acquired object, as these will determine how the museum is entitled to use it. Objects we acquire may be subject to copyright or design rights.

Copyright is an exclusive Intellectual Property Right which protects some types of work from being copied or used without permission of the rights holder(s). UK copyright law protects certain literary, musical or artistic works as well as film, broadcasts, sound recordings and typographic arrangements. Most copyright lasts for 70 years after the artist or designer’s death.

Design rights protect functional objects. They allow the rights holder(s) to commercially benefit from their designs for a limited amount of time: up to 25 years if creators register their designs and up to 15 years if not.

If the acquired object is still protected by rights, the curator will seek permission from the appropriate rights holder(s) to use images of the object and negotiate which terms of use they allow.

Getting them through the door

Once approved, we can then transfer title from the owner of the object to us, either by paying for it or having a legal document known as a Deed of Gift signed, and arrange for us to take possession of it.

Arranging for objects to physically enter the museum is always exciting – after what can be months of proposals, research, and planning. The method of transport depends on what the object is, and where it is coming from.

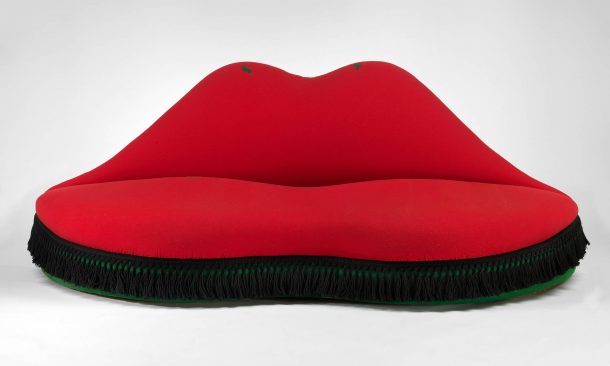

Iconic designs, such as the Mae West Lips sofa are often purchased from dealers or at auctions and are then shipped by professional art handlers.

However, many of our new acquisitions are more readily available: we have acquired newspapers, perfume bottles, trainers, and even plastic bags. Therefore, we usually arrange for them to be posted by courier. Where objects are purchased commercially, or through e-commerce sites, they are shipped to us as they would be to anyone else.

Once the objects are through the door, regardless of what they are, they are treated with ‘museum object’ status – which means handling with nitrile gloves, secure and environmentally-managed storage and locations recorded on CMS.

Giving the objects the care and attention they need

For the next step of the process, our Conservators assess the object and help us understand how to care for it. The V&A has specialists for almost any type of object and material you can think of, but we have certainly put them to the test with the materials in this gallery.

Plastic is a (relatively) new material and is notoriously difficult to conserve because of its varying chemical compositions. Many types of plastics are prone to deteriorating over time, such as early examples and single-use plastic. Sometimes investigation is needed with one-off examples such as a homemade plastic by designer Thomas Thwaits, part of his experimental ‘Toaster Project’: an attempt to make a toaster entirely from scratch.

However, it’s not just plastics we need to watch out for. We’ve acquired three hand-knitted pouches, designed to care for joeys orphaned in the recent Australian wildlife fires. For these, we needed to make sure we didn’t introduce any foreign species – it wouldn’t be a first as it’s believed that the Australian carpet beetle made its way to the UK in a museum object. To be on the safe side, we put our joey pouches straight in the freezer, where the low temperatures kill any bugs or pests. (Don’t worry, we triple checked for joeys.)

Strike a pose

New acquisitions are photographed by our Photo Studio. This records the condition of the object when it enters the museum, which gives us a reference point for condition checks. Just as importantly, the images are used on Explore the Collections – our online collections database – or by our Learning, Press and Marketing teams.

Of course, before images are used online or elsewhere, we make sure the correct copyright has been cleared.

How to keep track of millions of objects

The museum is home to over 1.5 million objects. While we can’t imagine forgetting any of the objects we’ve acquired, these objects will outlive our museum careers! Therefore, a standard numbering system is used across the museum to uniquely identify each object.

There are a few different ways that we physically mark objects, all of which are reversible and cause no damage. For paper objects we use a soft pencil, and for non-porous materials we use a layer of conservation grade clear acrylic (which is a bit like nail varnish) creating a shield that can be written on in ink. We even share a set of guidelines for how letters and numbers should be written – to avoid confusion with different handwriting styles.

Meanwhile… more paperwork

It’s at this point that we need to finish off the CMS procedure. Some of the information we input here – object descriptions, production details – will be used to populate Explore the Collections when the object record goes live. We try to make these records as thorough as we can, as this makes our collections more accessible. Explore the Collections is used by researchers, people curious to learn more about the objects they’ve seen on display or that we have in storage, as well as people who are not able to come to the museum in person.

Locked in the basement…

An Indiana Jones style museum store often springs to mind at the mention of museum storage, but in reality our stores are secure, tidy, and well organised (each shelf has a unique location code) – comparatively boring. Most of our objects spend some time in storage, even if it is only for a brief period while we prepare labels and mounts for display.

… or facing the public

All the objects we have acquired for the gallery are going on display. This is the ideal outcome for all new acquisitions, but sometimes objects go into store before an opportunity opens for them to go into a new gallery, exhibition, or even on loan to another institution.

We work with our Interpretation team to write labels explaining what the objects are in clear and concise language, while making sure the labels fit into the broader narrative of the displays. At the same time, bespoke mounts are made by Technicians or Conservators. These mounts allow us to hang lamps, put speculums on walls, fix bikes to plinths, and elaborately hang textiles. If you haven’t noticed how intricate some of these mounts are, it’s because our colleagues are so good at their jobs that they’re practically invisible!

And finally, we place the objects in the cases! And the visitors come in.

So, that is the story of how our objects find their way into the museum and in front of the public – it’s a big undertaking involving teams across the whole museum. We would love for you to visit and see the outcome of our work – or to check out our blog where you can read some more behind-the-scenes stories from this project.