To return to Napoleon’s marital affairs, today I’d like to introduce a great example of French porcelain from the Empire Period, that was part of a divorce gift rejected by Empress Josephine.

This dinner plate will feature in a display demonstrating how Napoleon made the decorative and fine arts central to his new image and how patronage of the imperial court helped to revive French manufacturing.

Taking a closer look at what might simply appear to be a rather attractive single plate, leads us via: impressive porcelain production; an impatient empress; the mystery of disappearing plates; Napoleon’s Egyptian Campaign; Egyptomania; and Amenhotep III …

This was one of 72 plates with views of Egypt that formed part of the Sèvres Egyptian Service 1810-12. Comprising of elaborate dinnerwares and architectural centrepieces, the service is one of the greatest examples of French porcelain to survive from the Empire period.

The service was originally made for Empress Josephine, partly as a divorce present from Emperor Napoleon. Josephine was involved with the commission of the service, which was produced by the highly regarded Sèvres factory. However, she lost patience with the time taken to produce the service and when it was finally delivered to her at Château Malmaison, on 1st April 1812 (203 years today!), the design was considered too severe and the whole service was rejected.

Following Josephine’s rebuff, the service was returned to the Sèvres factory. Despite Josephine’s aversion to its design, the service went on to be accepted and admired by others.

In 1818 Louis XVIII decided to give the service to Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, for his assistance in helping to restore the Bourbon monarchy.

When the service had been returned to the factory it was still complete with all 72 plates of Egyptian scenes, but when it came for it to be passed on to the Duke of Wellington only 66 of the plates were accounted for. Therefore ten plates in total (including four extras which had been produced) had been dispersed or lost. Three have been located in the Musée national d Céramique, Sèvres and there is also a plate in the British Museum which appears to be a unique and possible trial piece for the service.

The surviving service remained with successive Dukes of Wellington until 1979, when it was acquired by the Victoria & Albert Museum. Today, this plate is displayed at the V&A and the remaining service is on loan to English Heritage and displayed at Apsley House, London.

Dominique Vivant Denon

Dominique Vivant Denon (1747-1825) was an artist, collector, curator, diplomat and author who served as Napoleon’s Minister of Arts and first director of the Musée Napoléon (the Louvre).

The central designs on the dinner service plates were taken from illustrations by Denon, published in his account of his journey to Egypt during Bonaparte’s 1798 campaign, Voyage dans la Basse et la Haute Egypte (Paris 1802).

Napoleon launched a military expedition to Egypt in 1798, with the aim of seizing Egypt from the Ottoman Empire and blocking British trade routes. At Napoleon’s invitation, Denon accompanied the Egyptian campaign in the position of artist.

Through his work on this expedition, Denon appears to have been the first artist to document the temples and ruins at Thebes and other sites. He was in his element and enthusiastically produced hundreds of drawings. He marveled at many of the sites he visited and in his accounts commented:

‘I was ashamed at representing such sublime objects by such imperfect designs, but I wished to preserve some memorial of the sensations which I here experienced.’

Although deeply interested in the buildings, monuments and archaeology of Egypt, Denon also recorded landscapes and views from different places, as well as people currently inhabiting the area.

Although it was not a military success, the expedition was promoted in France as a national triumph, triggering a widespread fashion for all things Egyptian – Egyptomania. Denon’s drawings were one of the central sources for this new ornamental vocabulary.

Amenhotep III

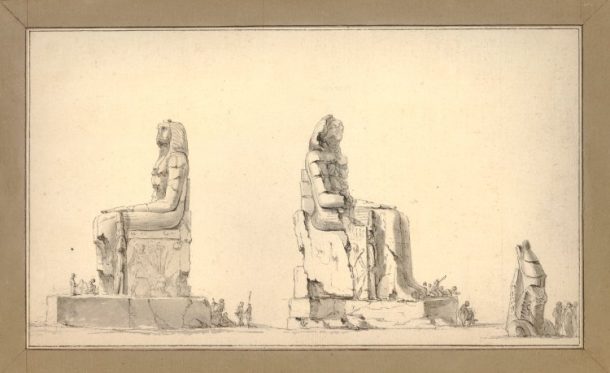

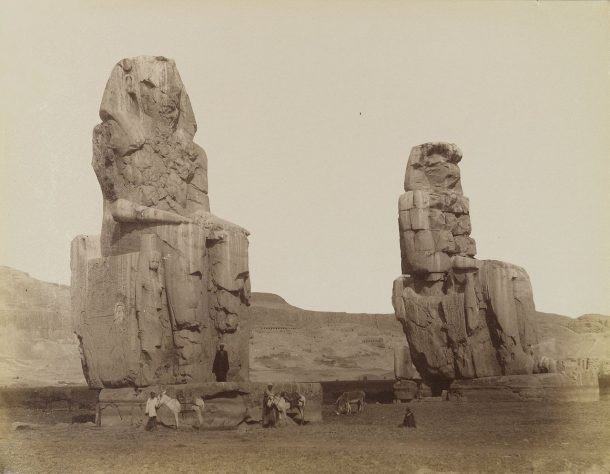

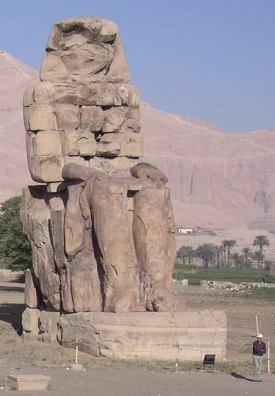

Our plate, entitled ‘Statues dites de Memnon’, has its central reserve painted in enamels with a landscape showing the statue of Amenhotep III at Luxor. Denon’s original preparatory drawings for this particular scene are in the British Museum.

Amenhotep III (also known as Amenhotep the Magnificent) was the ninth pharaoh of the eighteenth dynasty and ruled Egypt from ca.1387 BC to 1350 BC. Fittingly, given Napoleon’s own aspirations, Amenhotep III’s reign was a period of unprecedented prosperity and artistic splendour.

Amenhotep undertook extensive building projects, including his extremely large mortuary temple on the West bank of the Nile. Unfortunately, as it was built too close to the floodplain, within 200 years it was reduced to ruins and then much of the masonry was liberated by later pharaohs for their own building projects. The only elements that remained standing were the ‘Colossi of Memnon’ – two enoromous stone statues of Amenhotep that stood by the gateway of the temple. Including the platforms they stand on, both colossi are approximately 18 metres high!

The colossi were likely named after Memnon, King of Ethiopia, who was slain by Achilles as he tried to help defend the city of Troy during the Trojan War. The name Memnon means ‘Son of the Dawn’.

The statues are made from blocks of quartzite sandstone. The southern colossus is made from a single piece of stone but upper tiers of the northern statue are made from blocks of sandstone – the result of attempts at reconstruction by later Roman engineers.

Last time I was at Apsley House, the staff did not seem to be aware that this important service was on loan from the V&A.

I think at the least there should be a label with this information on in the case.

Many years ago the V&A produced an excellent booklet on this Service.

Could we not have an update.

Thanks for the explanation of why the north statue is partially of block-work. It’s always written they were of single pieces of stone, but that never fitted with the photos. In 2008 we tracked down the house in Cairo used by the expedition artists and scientists. It had been restored and opened as a house museum but was already in terrible shape, with all the text panels removed and stacked in a side room, and 2 rooms used as rubbish tips. Regardless, it was amazing to walk through the rooms where so much material for the Description was produced.