Zoe Allen, Senior Gilded Furniture and Frames Conservator

Phil James, Technician, Technical Services

This painted and gilded carved walnut chair is part of a suite of furniture made for Marie Antoinette’s Cabinet Particulier in the palace of Saint – Cloud outside of Paris. It was made by Jean-Baptiste-Claude Sené (1748–1803) in 1788 and was painted and gilded by Louis-François Chatard, (ca. 1749-1819), Both Sené and Chatard were principle chair makers and gilders to Louis the XVI and Marie Antoinette and this chair bears the makers stamp.

The V&A have a second chair and the rest of the suite has been scattered; Versailles have one chair, there is one in a private collection and the rest of the suite, a fire screen, a lit de repos (daybed) and a bergère (enclosed armchair), is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

This post presents a brief description of the conservation treatment that was carried out on the chair in preparation for its display in the new Europe galleries due to open later in 2015.

The chair has been re-upholstered several times, re-gilded and over-painted. The last intervention was in the 1970’s when it was upholstered in blue swagged fabric and partially painted a greyish blue.

Recent research carried out at The Metropolitan Museum of Art found evidence that the suite had in fact been originally upholstered with hand embroidered white fabric with a floral print and the fire screen retained the original fabric. It is believed that Marie Antoinette herself embroidered her initials on the fire screen. Examination of the surface decoration found the carved woodwork on the suite to have been originally partially gilded and painted white to match the fabric.

This information provided the remit for the conservation treatment of the V&A chair mainly to re-upholster with a more historically accurate fabric and to remove the blue over-paint.

Gilding

The gilding on the chair is water gilding, combining both matt and burnished areas, however it is not the original gilding. The gilding was overall in good condition with some flaking and surface dirt.

The surface was consolidated (laid back in place) with traditional techniques. Diluted rabbit skin glue is applied beneath the flake and carefully stuck back.

Surface dust had become embedded on the surface and detracted from the fine carved detail and was carefully removed during conservation treatment.

Removal of the blue paint

The surface had been overpainted blue/grey to match the 1970’s upholstery and this was removed during treatment.

Replacement of losses

There were several losses to the carving on the chair, the most visually disturbing being the cresting above the Marie Antoinette initials. The rest of the suite was examined to see if any chairs still had this area intact with a view of making a copy. The only chair with the top still intact was that at Versailles, however, on close inspection the carving was quite different in style. With each piece in the suite being hand carved it could not be expected that any two elements would be exactly the same.

We will never know exactly how the missing element appeared therefore the most sensible option seemed to be to copy and make a mirror image of what was already there.

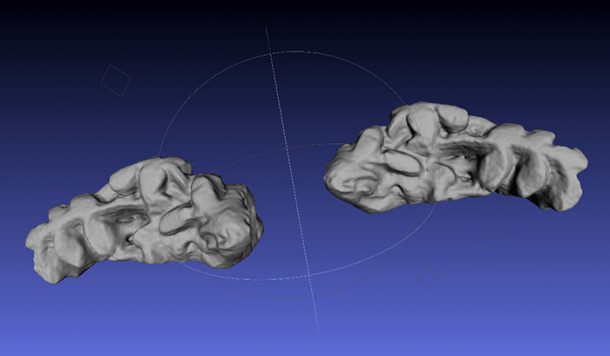

A mould and cast was made from the extant area of the crest. This was scanned, ‘reversed’, then 3D printed. A mould was made of the printed piece and recast in an inert material. This was then gilded and toned to match the extant original.

Castors had been added to the legs at some point and carved detail on the foot had been chiselled away to fit the castors.

Examination of the rest of the suite showed the bottom of the chair legs to have had a twisted rope ornament above a small bun at the base.

Using this information the castors were removed and new feet were made.

The chair had been re-upholstered numerous times and upholstery tacks had crushed the crisp gilded moulding on the edges adjacent to the upholstery.

All damaged areas to the gilded edges were carefully filled and gilded to re-instate the crisp moulded step.

Re-upholstery

As well as the gilding, the structural wooden frame was severely damaged by previous re-upholstery and re-introducing new nails was not an option.

For the re-upholstery the V&A engaged Xavier Bonnet of Atelier Saint-Louis, Paris, who is an authority on historic upholstery. In order for him to create the historically correct upholstery shapes, a firm attachment was required to withstand the tension of the different stuffed forms. A method needed to be devised which would allow him to upholster the chair without pinning directly into the wooden frame.

Systems had to be found that were not only easily removable and reversible, but which the upholsterer could work with in a traditional way. Other institutions have carried out similar works in different ways but the methods described here are possibly partly unique to the V&A.

The structures for the arms needed to be made of a flexible material that could be shaped over their compound curved shapes, and in their final form they had to retain their shape and not deform during upholstery. Resin-bonded carbon fibre, which is durable and has been used elsewhere for similar work, was not suitable here because the arms are slightly pinched-in where the bare wood meets the gilded moulding and it would have been too stiff to easily remove and put back without risking damaging the wood. The bonding process is also unpleasant, requiring a controlled restricted environment, and you really have a limited time to get it right.

We experimented with several different materials and found that Buckram fabric, a cotton or linen material, saturated with wheat-starch paste, also used for making textile and costume supports, could be easily shaped over the arms and, built up of several layers and clamped tightly in place, once fully dry would be flexible just enough to be repeatedly removed and replaced without deforming. The process is non-hazardous, is not time critical, can be done anywhere and if necessary the dried structures can be wetted and re-worked.

The arm was prepared with cling film used as a separator. The linen fabric is then saturated with wheat starch paste and layered onto the arm. Once fully dry a flexible form is created that can be removed and replaced without deforming.

Dried and trimmed forms with shaped wooden supports were then ready to be covered with the next layers of linen. Poplar wood was chosen as it is a close-grained wood that will hold the upholsterer’s tacks.

The padded former was filled with horse hair. There is a 5mm pocket around the formers’ edges to allow the upholsterer to sew the cover to the buckram base.

The bare back of the chair needed another structure to support the upholstery. The shape of the chair back includes compound curves and is not symmetrical. A wooden stretcher-frame of poplar wood was made and assembled to fit the chair’s back shape as closely as possible. It could then be upholstered off the chair, protecting it, in particular its fragile gilding, from any of the effects of that work, such as impact and vibration from hammering. This ‘sub frame’ was held in place on the chair back by removable brass clips screwed into the corners of the stretcher.

The wooden support was angled along the front and back surfaces to aid the upholsterer in shaping the padding.

The chair has now been returned to a near original appearance and is ready for display in the new galleries. Its success is the result of a fascinating collaboration between curators, conservation, technical services and the upholsterer.

Thanks to Loredana Mannina (Furniture Conservation Intern) for her help with filling and Rozi Rexhepi (Digital design artist in residence April-October 2014) who carried out the scanning for the 3D print.

A fascinating description and the chair ( which I remember well from the previous European galleries ) looks splendid with its renewed gilding and upholstery. I wonder why, though, only one chair was conserved in this way when the V&A owns a pair? I’m sure it was expensive to restore the chair but are there plans to transform the second one? I find it odd that the V&A would exhibit one as a “specimen” when it is fortunate enough to own two chairs which belonged to Marie Antoinette ( and otherwise has few pieces of French royal furniture ).

It seems to me that there’s something to be said for leaving one of the chairs in its current condition. In some ways, it is just as fascinating to view an object that has not been restored and consider its transformation over time. Certainly that can also tell a story about the object and its owners through the years. I appreciate that there is one fully restored chair and one left intact.

Well, yes, Debra, except that the other chair is left as restored ( including re-painting and upholstery ) by the V&A in the 1970’s. If it was in “original condition” ie late 18th century, I would agree but now there is one chair as restored in 2014 and its pair in the 1970’s interpretation. I imagine that current thinking is that the most recent restoration is nearer what Sene intended.

Fascinating article. I wish they would have said something about the upholstery fabric, though. At the beginning, the chair is described as originally being upholstered in hand embroidered fabric. Is the fabric they used for the reupholster hand embroidered as well or did they go with some kind of manufactured reproduction?

Please do tell us about the fabric

I agree. The change in the fabric is dramatic. I would have loved to have seen a photo of the fire screen that retained the original fabric. Great article, however, showing the steps of a very intricate process.

This article is the first of a series on the re-upholstery of several pieces of seat furniture currently undergoing treatment. While this article focusses on the conservation of the chairs framework an article will shortly follow with more information on the fabric itself and the upholstery.

I agree that the furniture restored to the way it was intended to appear by the artist(s) is preferable; especially with French Royal pieces. I have become obsessed with the St Cloud furnishings as they were the zenith of French decorative arts. Moreover, I was lucky enough to discover a suite of seat furniture that was a meticulous copy of the St Cloud Marie Antoinette’s cabinet intérieur suite and have spent a king’s ransom upon the restoration of the water- gilt and upholstery but, is truly a marvel. I can appreciate the effort that was put forth on this chair.

BTW if you would like more information on the reproduction of the fabric and the fire screen, go the the Metropolitan Museum of Art New York’s web site

A very gentle and efficient approach towards the restoration of the chair,

Thanks to the team ,

Since you are going to post a series of restoration projects, could you add some videos as well as pictures.

Great article.

The wheat paste troubles me, insects like it. Mark Anderson at Winterthur made similar forms by impregnating linen with epoxy. Also If the wood used was tulip poplar, it doesn’t interact well with iron over time. Also very soft and tends to shred. Xavier Bonnet is a genius.

Wheat starch paste is widely used in conservation and there have been no reported problems to date. However like all the multiple natural products used in our field all carry a small potential pest risk. This is mitigated by stringent environmental control.

Over the last few decades numerous fantastic solutions have been found by conservation colleagues worldwide for the problem of reversible upholstery. This same problem has many solutions and this method is just one more tool to add to the box.

This is very attractive work on wood. Basically chair making design is attract me. I like this very much. This is very creative job. Thanks to the team which made these.

Mary-Antoinette Courbebaisse: A Victorian woman that had a place with an illustrious family and was respected by quite a few people all over the planet.

Mary-Antoinette Courbebaisse