Today marks the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo, which was fought on Sunday 18th June 1815, near Waterloo in present-day Belgium. The battle saw Napoleon and his French army defeated by the armies of the Seventh Coalition -comprising of an Anglo-allied army, commanded by the Duke of Wellington, and a Prussian army commanded by Gebhard von Blücher.

Those who like interpretations of history to be very much ‘brought to life’, will no doubt be interested in the rather grandiose reconstruction of the battle taking place this weekend, that promises to involve 5000 re-enactors, 300 horses and 100 canons. In the spirit of today’s internet era, any interested parties are also able to watch the re-enactments streamed live on-line, here.

The new Europe Galleries acknowledge the importance of 1815, a year regarded by many in the 19th century as ushering in a comparatively peaceful period for Europe.

Gallery 1 is titled ‘Luxury, Liberty & Power 1760–1815’. Following a display demonstrating Napoleon’s influence on European art and design, the gallery then culminates with a striking display of the impressive ‘Wellington Service’. Also known as the ‘Portuguese Service’, this silver service was presented to Napoleon’s victor, the Duke of Wellington in recognition of his efforts in the preceding Peninsular War (1807-1814).

Intended to glorify the Triple Alliance between Britain, Spain and Portugal and celebrate their joint victories against the French between 1808 and 1814, for the Portuguese, this was their great gift to the man who had ensured their independence.

The service was designed and executed under the control of Domingos Antonio de Sequeira (1768-1837), court painter to Dona Maria I. Although plans for the production of the service were well advanced by March 1811 the actual date when the decision was taken to present the service is unknown.

The entire service consists of 852 objects. The centre piece of the service can be see on display at Apsley House but that still leaves us with a lot of dazzling pieces to contend with here at the V&A.

Sequeira kept running into practical problems while producing the service, such as his craftsmen being called up for military service. However, by September 1816 the service was finally shipped to Britain – the total cost of the service being around a staggering£27,000. Interestingly, despite all this work and expense, the Duke later needed to acquire additional items so that the service met British dining practices.

Elsewhere in the Europe Galleries, a number of connections to the Battle of Waterloo and its leading men can be found.

The nineteenth century gem-engraver and medallist Benedetto Pistrucci was commissioned to make this portrait in wax of Napoleon during the so-called one hundred days, between Napoleon’s return from exile on the island of Elba and his defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Pistrucci recorded in his autobiography:

‘I made a model in wax of Napoleon- though not from a sitting, but I had many opportunities of seeing him very well- at chapel, in his garden, and in public, when he reviewed the troops- so that always comparing him with the wax model, which I kept in my pocket on purpose, with a little trouble, I at last completed a portrait which was considered extremely like, and was, I believe the last portrait of him taken in Europe.’

These two guns from the Cabinet d’Armes of Louis XIII of France, were amongst a number of firearms brought to England from Paris as ‘trophies of war’ after the Battle of Waterloo.

This wall panel is from a series that almost certainly originally formed the main decoration of the Salon in the Hôtel Grimod de la Reynière in the Place Louis XV (now Place de la Concorde), Paris, built in 1769 , which was the official residence of the Duke of Wellington during the occupation of Paris.

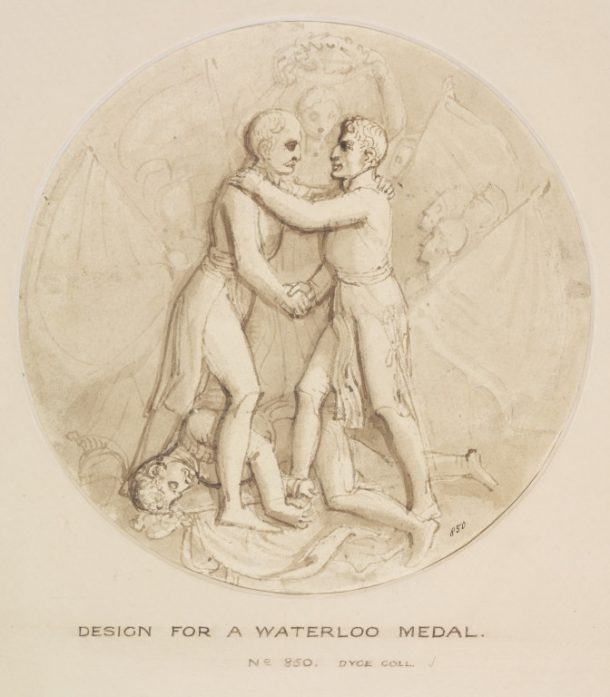

Outside of the Europe Galleries, our Prints & Drawings collections contain many objects directly referencing the Battle of Waterloo. I was drawn (pun intended) to this design for a medal depicting Wellington and Blucher embracing on the field. A French standard bearer lies at their feet and Victory holds a crown above their heads. I particularly like the fact that ink blotches make it look as if they both have black eyes and that Victory’s face appears unintentionally ghostly and rather haunting.

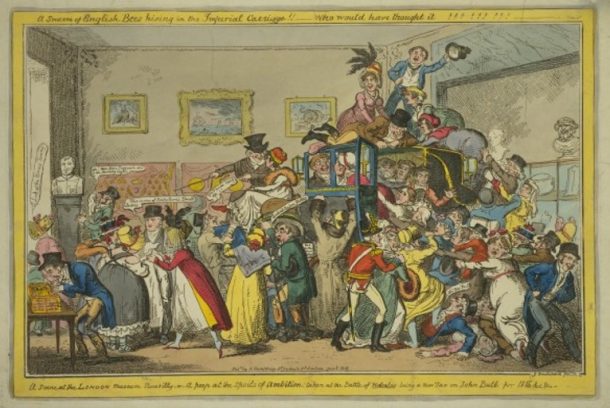

The firearms mentioned above were not the only ‘war booty’ to make their way over to England following the Battle of Waterloo. Napoleon’s carriage and its contents were captured after the battle and ended up in a private London museum. In this entertaining 1816 print by George Cruikshank, the carriage is seen eliciting a variety of reactions from a throng of enthusiastic visitors, many of whom are keen to try out the carriage for themselves rather than just looking at it.

NB: We’re hoping that visitors to the new galleries will demonstrate interest in the objects with rather more decorum …