One of the best things about working on the Factory project is the range of different artists and designers that we come across while cataloguing. The V&A’s collection of works on paper is huge (741,000 objects and counting!) and amongst the famous names like Constable and Raphael, there are a wealth of fascinating and talented artists whose work you may not be as familiar with. Through this series of posts, we aim to bring some of the works of these artists and designers into the limelight.

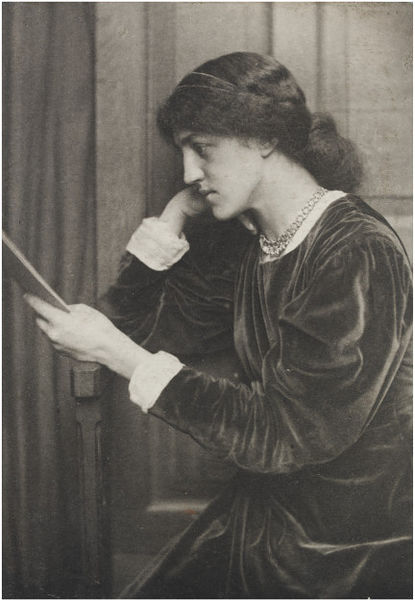

In this post I want to celebrate the life and work of May Morris, an artist with a well-known name, but who is often overshadowed by her more famous father.

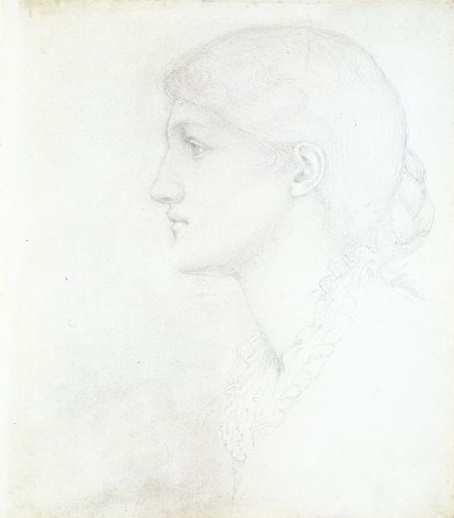

May was the daughter of William and Jane Morris, and grew up steeped in the world of Arts and Crafts and the Pre-Raphaelites, visiting the workshops of Morris & Co. with her father, and posing for artists including Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones. Her mother and aunt taught her embroidery, for which she showed an early talent, and they encouraged her to develop her own designs.

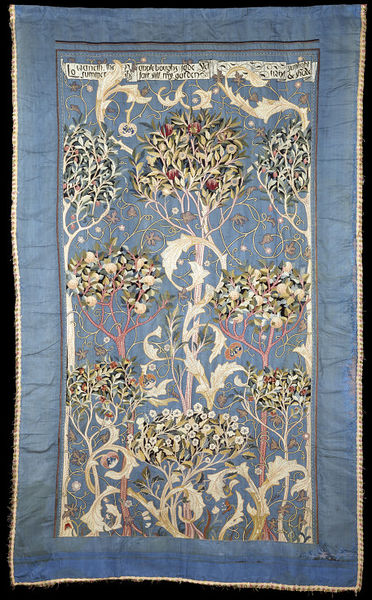

After studying textile arts at the South Kensington School of Design, she took over the embroidery section of Morris & Co. in 1885, aged just 23, and took responsibility for all new designs as well as executing the larger, more complex commissions such as wall hangings, altar cloths and tapestries. Her designs followed the Arts and Crafts aesthetic, using stylised natural forms, flowing lines and influences from medieval art, and they used directional stitches to add texture and give an impression of movement. This was embroidery as art, elevated from its normal domestic context.

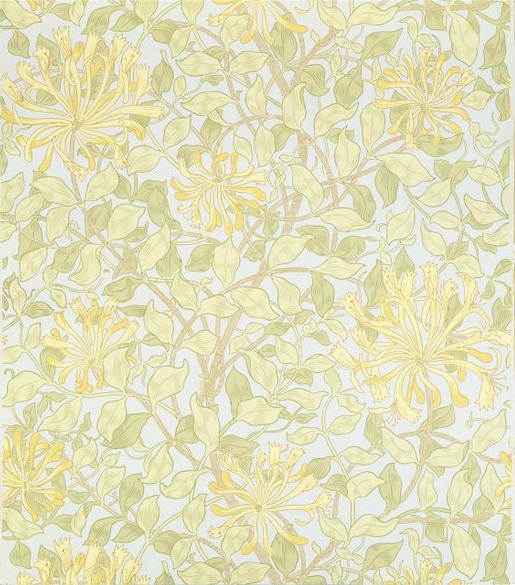

May also designed jewellery and wallpaper, including the beautiful honeysuckle design below, in which she shows a flair for translating natural forms into repeating patterns that matches her father’s. After William’s death she left the firm, although remaining as an advisor, and became a passionate and vocal advocate of craft and particularly embroidery, writing articles and a book, teaching at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, embarking on a lecture tour of America, and co-founding the Women’s Guild of Arts.

May clearly admired her father greatly, spending her later years editing his 24-volume collected works and building a memorial hall in his honour in his home village of Kelmscott. In her will she gave Kelmscott Manor to the University of Oxford on the understanding that ‘no modern innovations, improvements or installations be put in or made to the House in view of its age and its historic interest as the Home of the late William Morris.’ She also donated examples of William’s designs to the V&A for a proposed ‘Morris Room’, with seemingly no expectation of her own work being included. Despite, or perhaps because of, this modesty, I believe that May deserves to be recognised in her own right for her talent and her contribution to the Arts and Crafts movement, particularly her work in increasing the appeal and visibility of embroidery as an art-form.

The works on paper featured in this post, along with many more examples of May Morris’ work, are available to view in the Prints and Drawings Study Room (by appointment).