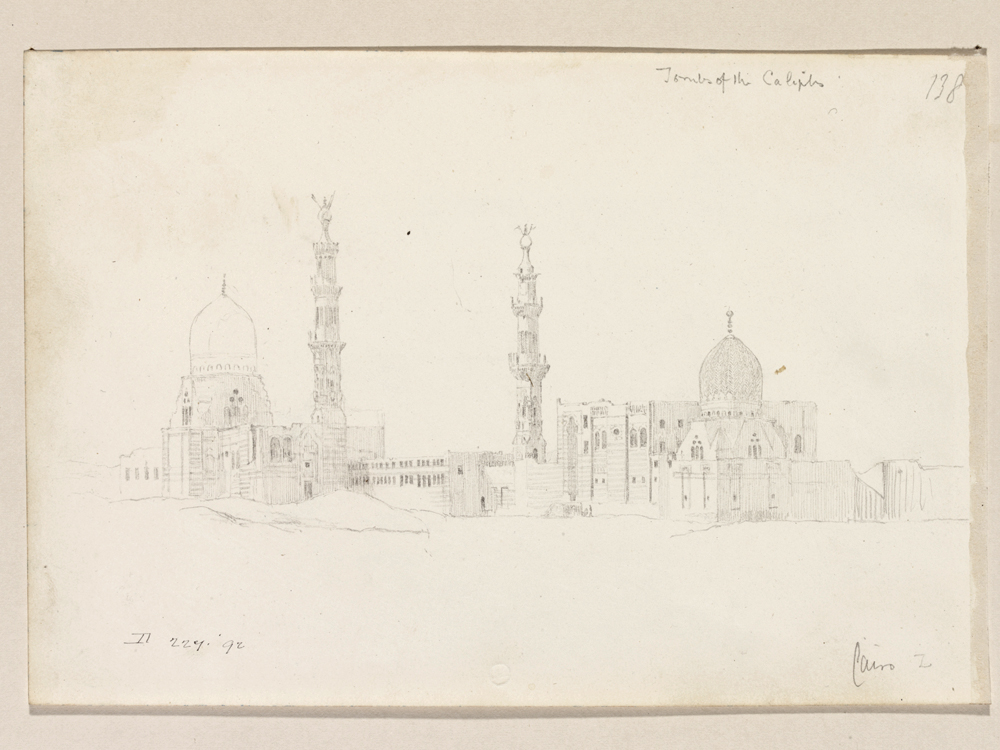

Museum no. D.238-1892 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Richard Dadd is perhaps most famous as the Victorian fairy-painter who killed his father and subsequently spent 40 years as an inmate of Bedlam and Broadmoor. Although accurate, this oversimplifies the life and career of this extremely talented and troubled artist. Dadd suffered a breakdown whilst travelling with his patron in the Middle East in the 1840s, an episode from which he would never fully recover. The V&A holds a fascinating collection of pages from one of Dadd’s middle-eastern sketchbooks, made at the very time when his mental health started to rapidly deteriorate. They show his incredible skill as a draftsman, and give us a glimpse of the sights and sounds that immersed him at this pivotal point in his life.

Richard Dadd was born on 1 August 1817 in Chatham, Kent. He showed artistic promise from an early age and, having studied at the Royal Academy Schools, he seemed poised to begin a successful and distinguished career. Held in high esteem by his peers and contemporaries, he was described as ‘invariably gentle, kind, considerate and affectionate’ and showed great dedication and passion for his profession. These qualities led to his introduction to the former Mayor of Newport, Sir Thomas Phillips, who was preparing to embark on an extended tour of Europe and the Middle East and wished for an artist to accompany him.

The Middle East held a particular fascination for artists and travellers in the early 19th century, as travel across Europe and beyond became easier and details of the vibrant cultures and people filtered back to the West. Sir Thomas was just one of many who felt the draw of these distant lands and decided to see and record them for himself.

In the early 1840s, photography was still very much in its infancy and sketches and paintings were the only tried and tested medium for visually capturing a great adventure such as this. Before the portable camera or ready availability of photographic mementos, travellers might collect souvenir prints of the sights they had seen, or perhaps even make sketches themselves to record their journey. Sir Thomas had settled on taking an artist with him for just such a purpose, and Dadd was recommended to him as someone whose technical ability and ‘amiable qualities’ would make him an ideal choice of companion.

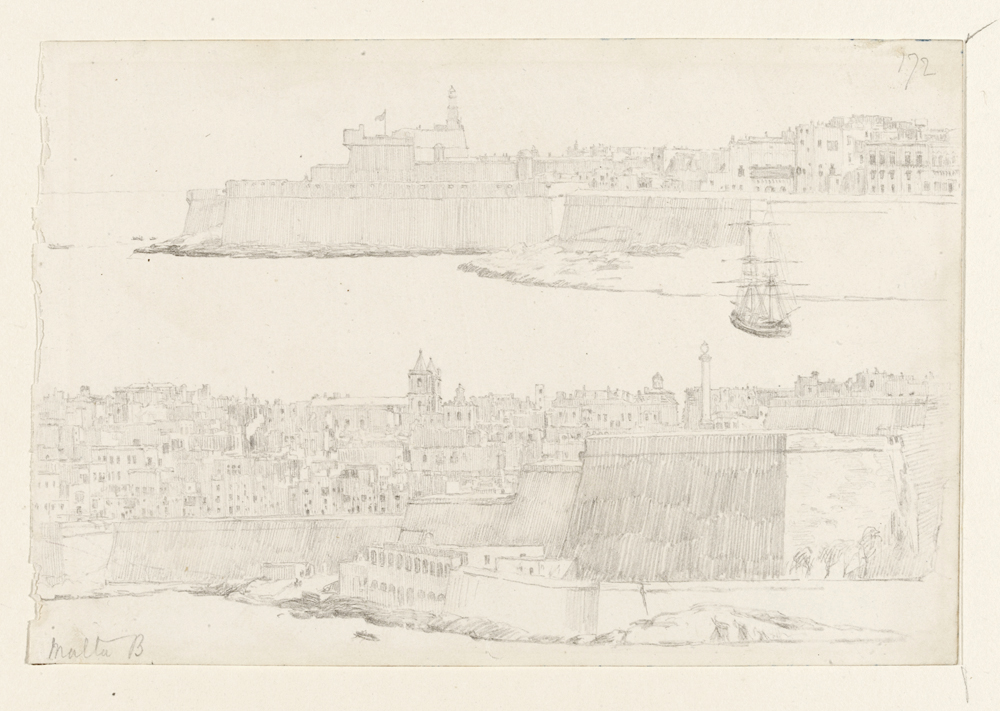

Museum no. D.259-1892 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Dadd’s high level of technical skill as a draughtsman is evident throughout his sketchbooks.

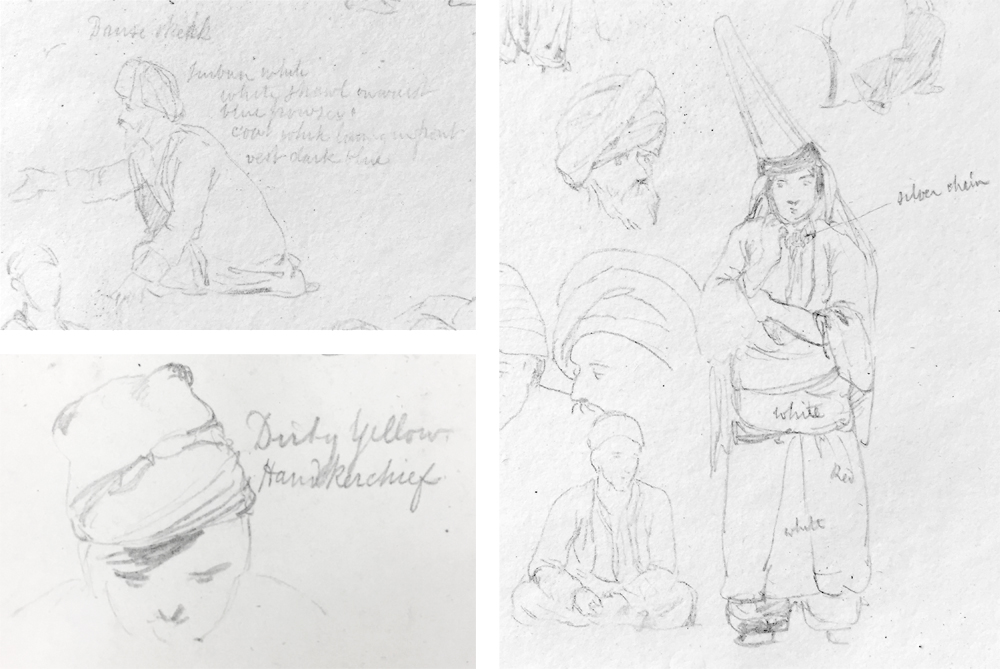

On 16 July 1842, patron and artist set out for Ostend and from there travelled through Northern Italy, Greece and Turkey, where they visited many ancient sites and ruins. Dadd carried with him small sketchbooks in which he made pencil studies of the architecture, landscapes and people that they encountered. These drawings range from portraits and quick but highly precise sketches of local scenes, to minutely detailed studies of temples and buildings.

Museum no. D.178-1892 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

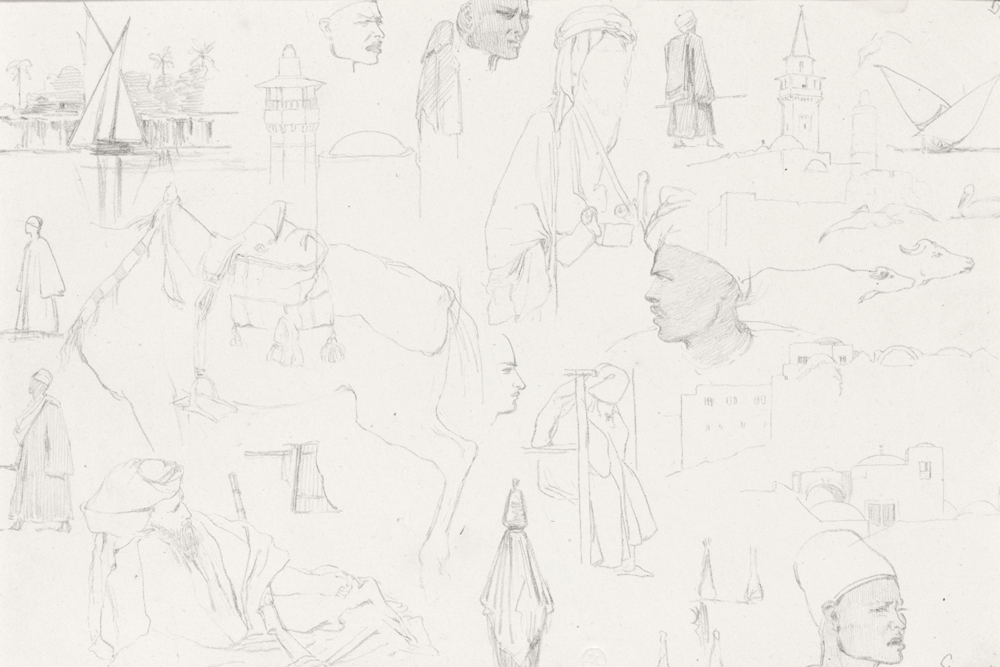

These quick sketches of people, animals, boats and buildings show Dadd recording the minutiae of everyday Egyptian life.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

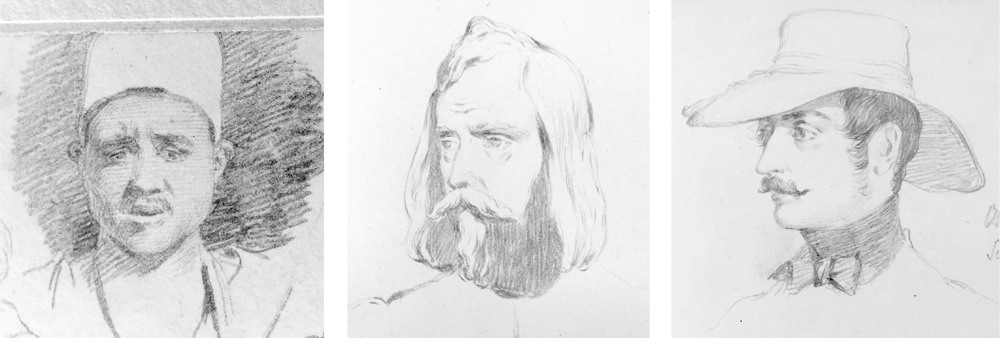

Dadd could capture the character and details of faces and costumes on a miniature scale – these drawings are only 2-3cm high.

Many of these drawings are annotated in Dadd’s tiny, almost unreadable handwriting. He jotted down colours and patterns and made careful notes on what he saw, probably to aid him in creating larger finished pieces at a later date.

Museum no. (bottom left) D.256-1892 (top left and right) D.166-1892

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Dadd often made notes of the colours, patterns and unusual details of what he drew.

These drawings are particularly interesting as they show Dadd grounded solidly in reality – here, his meticulous attention to detail is used to accurately capture the buildings, views and people that surround him. His most famous works are equally meticulous, but the subject matter is often fantastical and surreal – fairies, goblins and tiny people inhabiting strange, distorted worlds. The sketchbooks illustrate the highly refined observational and technical skill that underpins all of Dadd’s work.

Dadd’s drawings provide us with a fascinating record of local costume and culture.

Museum no. D.134-1892 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

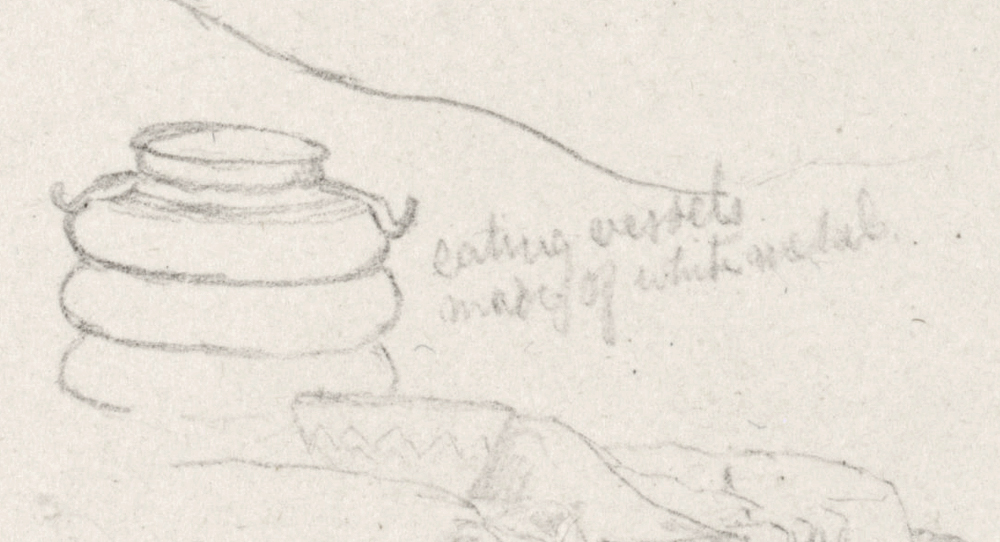

The two handled pot in the centre of the page is annotated “eating vessels of white metal” and sits next to a small bowl decorated round the outside with a simple zigzag pattern.

Museum no. D.146-1892. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Dadd made many drawings of camels in his sketchbooks. Here, he skilfully records the intricate saddles, blankets and harnesses, as well as the camels’ poses and expressions.

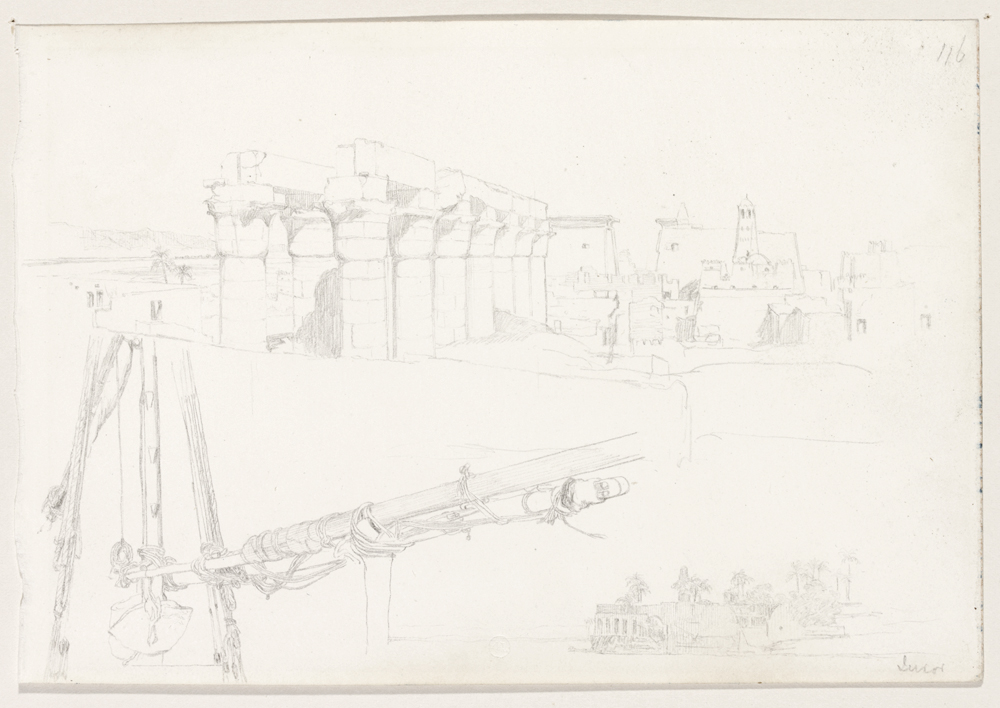

Leaving the Mediterranean behind, Dadd and Phillips began what proved to be the most physically and mentally gruelling leg of their journey. Travelling through Lebanon, Palestine and Syria, they were plagued by extreme conditions and challenging terrain. The pair finally reached Alexandria on 28 November, before travelling on to Cairo. It was whilst in Egypt that Dadd began to show the first signs of mental instability and unusual behaviour – symptoms that were at first attributed to sunstroke. He described his time in Cairo as being filled with ‘the most unaccountable impulses that would not let me stop to sketch, but were constantly prompting me on, to drink in, with greedy enjoyment, the stream of new sensations’. The Egyptian pages of the sketchbook are especially interesting, as they provide a tangible yet ambiguous insight into Dadd’s mind at exactly the point that it was starting to unravel. Far from suggesting mania or loss of control, the sketches are extremely disciplined, precise and startlingly accurate.

Dadd uses dense block hatching to show the strong shadows cast on the columns by the Egyptian sun. The detail and foreshortening of the boat rigging in the left hand corner has an almost photographic quality.

Museum no. D.205-1892 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This tiny thumbnail sketch of buildings and palm trees in the corner of the page is only 4cm long, but is still full of detail.

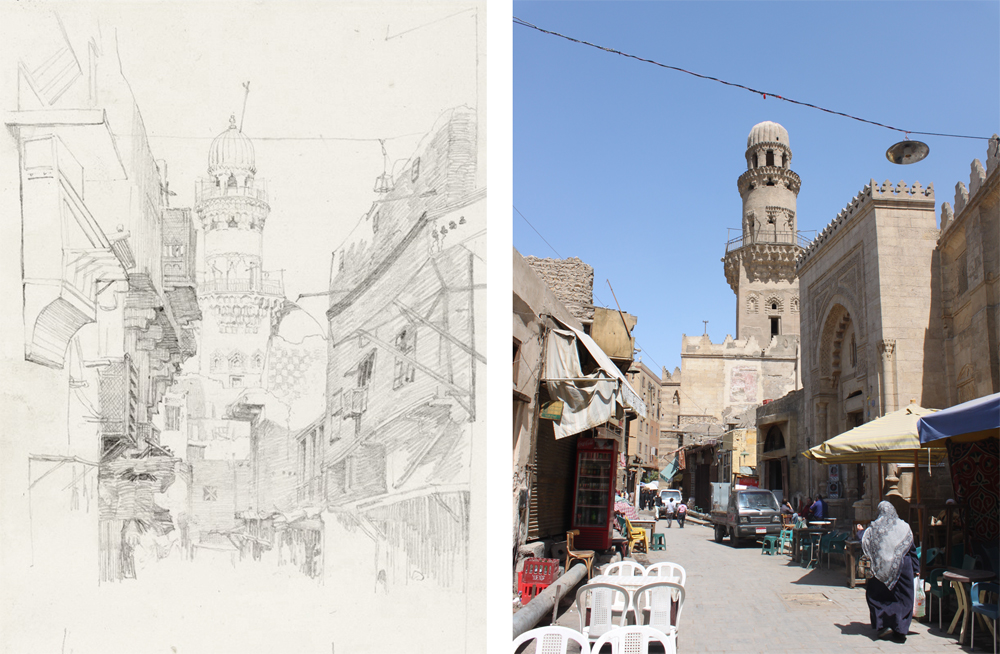

173 years later, it is still possible to identify some of the places Dadd drew and link them to photographs present in the V&A’s collection. The almost photographic quality of the drawings has proved especially valuable, as many of the views of Historic Cairo that Dadd captured were destroyed in the modern expansions of the city. His sketchbooks provide a rare record of Cairo’s disappearing domestic architecture, famous for its projected wooden interlaced windows, called mushrabiyya. They also show the vibrant street life of Cairo in the 1840s, capturing fleeting moments and interactions.

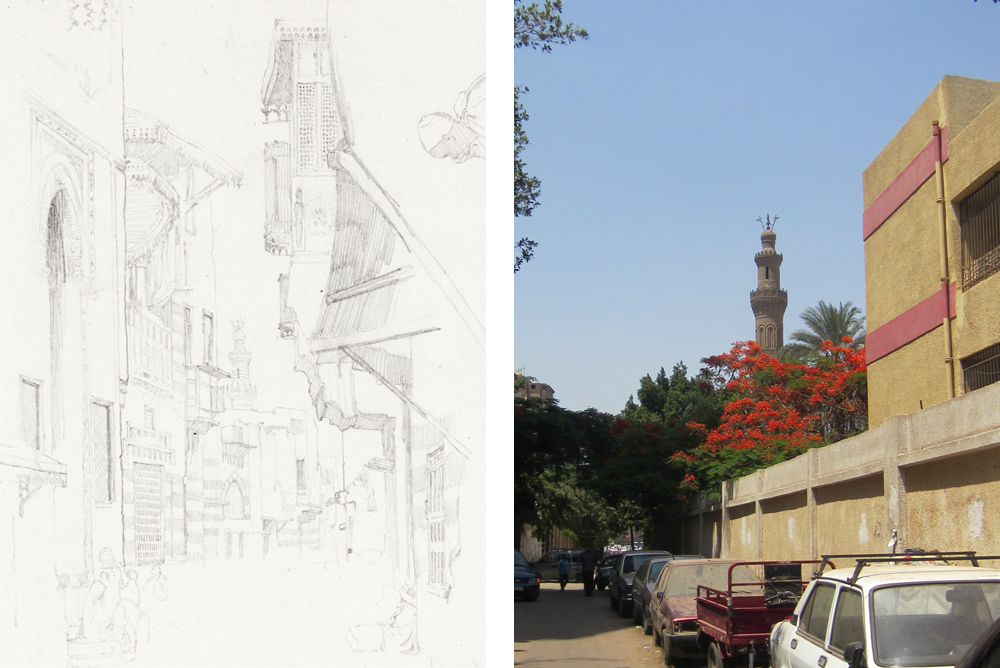

Museum no. D.228-1892 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Right: A modern view of the same street, illustrating how much of the architecture of Old Cairo has been lost – only the minaret still stands. © Omniya Abdel Barr

Right: The minaret of the mosque of Emir Bashtak is the only surviving feature of the view that Dadd drew. © Omniya Abdel Barr

Centre: ‘The madrasa of Mamluk Amir al-Sayfi Sarghitmish and the Saliba street, Cairo’. Francis Frith, 1856-1860, Egypt. Albumen print. Museum no. PH.2086-1894 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Right: ‘Madrasa of Mamluk Emir al-Sayfi Sarghitmish, main façade’. K.A.C. Creswell, 1916-1921, Egypt. Gelatin print. Museum no. 3425-1921 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

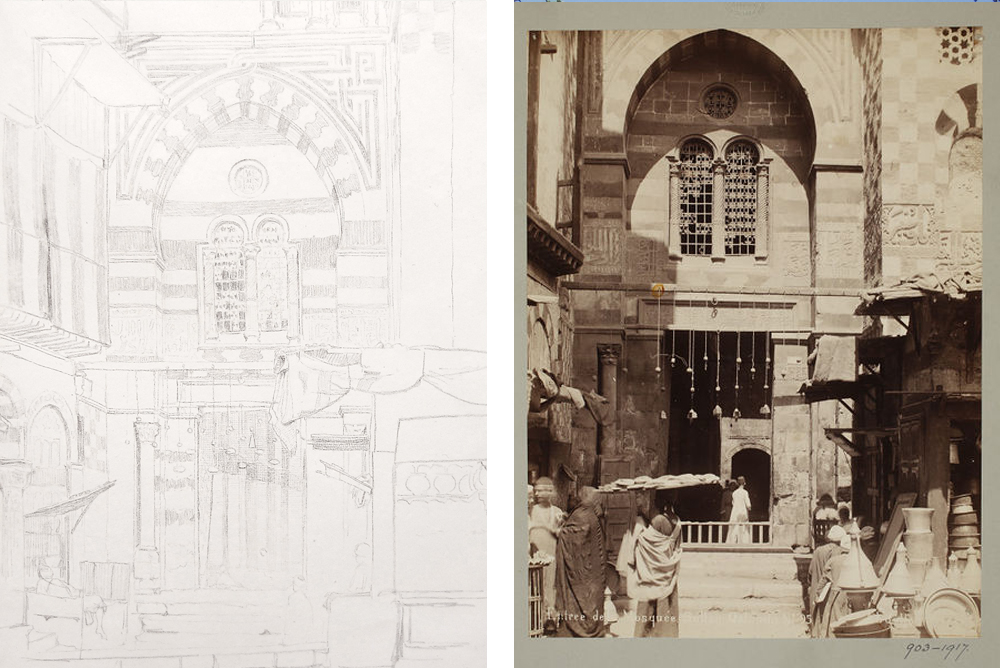

Right: ‘Funerary complex of Mamluk Sultan al-Mansur Qalawun, entrance’, Cairo. Frères Abdullah, c.1886-1895, Egypt. Museum no. 903-1917 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London This photograph, taken by Frères Abdullah around fifty years after Dadd’s sketch was made, shows how little this scene had changed in the interim.

This sketch by Dadd shows the Mosque of Sultan Hassan prior to the construction of the Mosque of al-Rifai.

Bottom: View over the Madrasa of Sultan al-Nasir Hassan. Hippolyte Arnoux, late 19th century, Egypt. Museum no. 1210-1912 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This photograph by Hippolyte Arnoux shows the same view, with the Mosque of al-Rifai under construction – scaffolding is just visible to the right hand side of the Mosque of Sultan Hassan.

On the return journey to England, Dadd’s behaviour became increasingly erratic and delusional. In May 1843, convinced that he was being pursued by evil spirits and possessed by the Egyptian God Osiris, Dadd abandoned his patron in Paris and made an abrupt return to London. On his arrival home, the dramatic changes that the ten-month long journey had wrought were immediately apparent to Dadd’s friends and family. He was paranoid, depressed, unpredictable and sometimes violent. When his rooms were later searched, they were found to contain hundreds of eggs which, along with ale, had been his sole source of nourishment during this time.

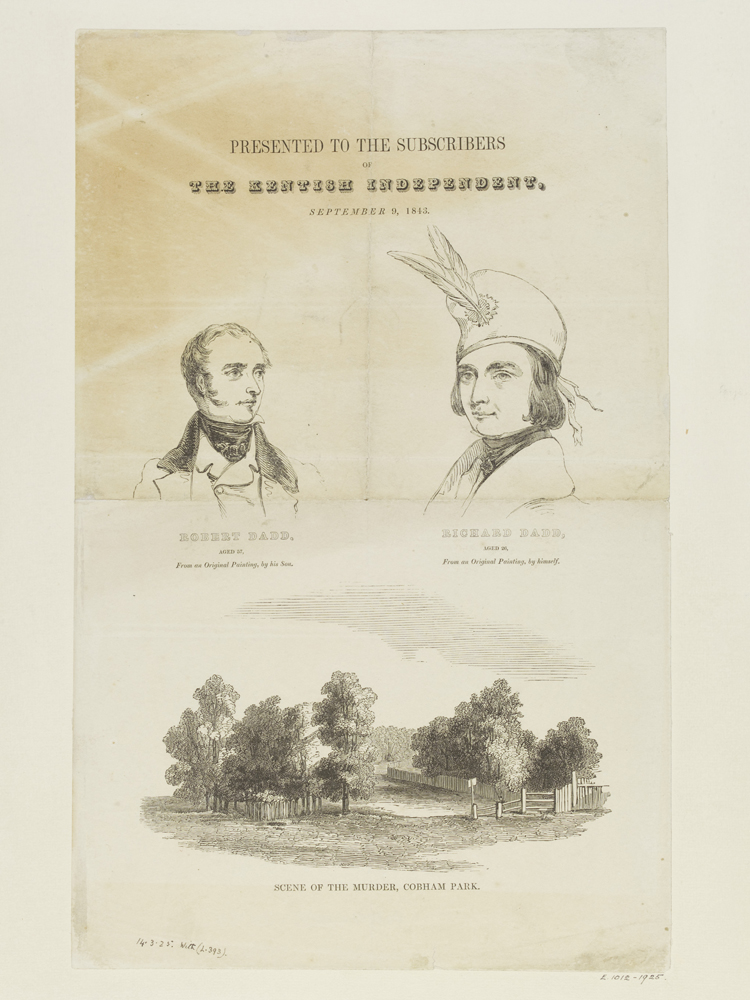

On 28 August 1843, Richard Dadd persuaded his father to accompany him to Cobham in Surrey, assuring him that this familiar haunt was the only place in which he would feel able to speak openly of what troubled him. Whilst walking in Cobham Park, Dadd fatally attacked his father with a knife, believing him to be possessed by the devil. The murder was entirely premeditated: ‘I inveigled him, by false pretences, into Cobham Park, and slew him with a knife, with which I stabbed him, after having vainly endeavoured to cut his throat’.

Sheet issued to subscribers of ‘The Kentish Independent’ newspaper in September 1843 after the murder of Robert Dadd by his son Richard, featuring portraits of the two men and the scene of the murder at Cobham Park, Surrey.

When Dadd was eventually apprehended, it was established by the courts that he was suffering from an acute stage of mental illness. Having been declared insane and therefore not capable of standing trial, he was admitted as a criminal lunatic to Bethlam Hospital at St George’s Fields, Southwark (now the Imperial War Museum), and was subsequently moved to the newly finished Broadmoor in 1864. After more than forty years of incarceration, during which time he continued to paint and draw prolifically, Richard Dadd died of consumption at Broadmoor on 8 January 1886, and is buried in the cemetery there.

In the months following his breakdown, the sketchbook containing these drawings was acquired from Richard Dadd’s family by Sir Thomas Phillips. The dramatic decline in Dadd’s mental health had prevented him from completing the job for which Phillips had engaged him. With some delicacy, and showing much affection for his ‘poor friend’, Sir Thomas expressed his wish to acquire the sketchbooks from the trip, along with the few completed artworks that Dadd had produced during the brief interval between his return to England and the murder of his father:

‘Whilst abroad he made very few drawings but interested himself with collecting materials in his sketch books for works to be thereafter executed. Knowing his principles to be strictly honorable I never recurred to the arrangement between us but meant on our return to suggest to him that he should keep the sketches & furnish me with drawings. The circumstances under which he returned prevented my alluding to the subject but the same views appear to have occurred to him & he engaged himself in making drawings for me which I left with him. These I apprehend are not numerous & I should certainly now like to possess his sketch books as well as the drawings he has made & I have so apprised his brother who says that at present his rooms are locked up… Whatever arrangement may appear to you fair I would at once accede to. I estimate my payments for him at £250 or something more.‘

Sir Thomas Phillips to David Roberts, 10 September 1843

Watercolour based on the sketch above. Although highly detailed and polished, the technique is still relatively loose when compared to Dadd’s other finished works in watercolour. This could suggest that this was a ‘quick’ watercolour sketch, made whilst Dadd was still in Egypt, rather than a finished piece completed on his return to England.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This photograph shows a view of funerary complex from the South – the opposite side from which Dadd sat when he made his sketch.

On 26 July 1892, this sketchbook was acquired by the Victoria and Albert Museum for £30 from W. P. J. Phillips – presumably a relation of Sir Thomas, who died of paralysis on 26 May 1867. The leaves of the sketchbook had been detached from the original binding and mounted in a volume, fitted with a lock and supplied with a black leather cover. A second sketchbook, which Dadd was allowed to keep with him during his time in hospital, now resides in The Bethlem Museum of the Mind collection, and is still bound in its original leather covers.

The pages from Dadd’s sketchbook, along with the photography of K.A.C. Creswell, Frères Abdullah , Hippolyte Arnoux , Francis Frith and Frank Mason Good are all available to view in the V&A Prints and Drawings Study Room, which is open to members of the public Tuesday-Friday, from 10am to 5pm.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Omniya Abdel Barr for her invaluable and extensive knowledge of the architecture of Cairo, and of the artists and photographers who have captured the city in their work.