There are a number of examples of sculptures created in the 20th century using synthetic materials that have already degraded to a point where conservation is unfeasible (and sometimes even impossible). This can also be the case where where works have been made with electronic components that have become obsolete and impossible to replace. In these contexts, sometimes the only choice available to conservators and curators is to create an accurate reproduction of the work. Recently, advances in the quality and affordability of 3D scanning and printing has meant these technologies are now very much within reach, and have given conservators a wider scope for creating facsimiles of works of art previously considered too damaged to display.

‘Play it Again SAM’ is one of four projects that form part of the ‘Design with Heritage’ project, and represents a collaboration between the Centre for Sustainable Heritage at University College London and the V&A Conservation Department. The purpose of the project is to investigate ways in which digital design can be used in exhibition and conservation contexts. The research, which is being carried out in the V&A’s Conservation Science Section, is intended to look into alternative methods for conserving and preserving works of art through the creation of facsimiles via new advances in 3D scanning and printing.

SAM (Sound Activated Mobile) is a kinetic sculpture by the artist Edward Ihnatowicz created in 1968. Ihnatowicz was an early pioneer of computer-based and cybernetic art. His works explored interactions between sculpture and audience, and created some of the first computer based, interactive robotic works of art. SAM was one of the earliest works that responded directly and recognisably to its immediate environment. It was displayed at the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London in 1968, “a demonstration of contemporary ideas, acts and objects, linking cybernetics and the creative process”, and later toured the US and Canada. You can watch some original footage of SAM interacting with viewers here.

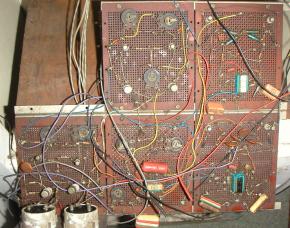

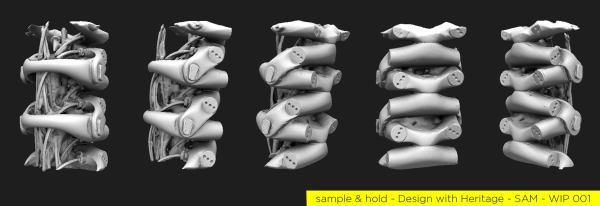

SAM was built using miniature hydraulic pistons inside a moveable vertebrae-like structure, surmounted by a large fibreglass parabolic reflector with four microphones in the centre. A simple analogue electronic circuit was mounted on the back, feeding information to the hydraulic hardware that was concealed in SAM’s plinth, instructing it to move as it received sound information from its surroundings.

SAM’s construction and inner workings are described in considerable detail in Alex Zivanovic’s site dedicated to Ihnatowicz’s work here.

Although SAM is still in existence today, it no longer functions due to the absence of some of its hardware. Since many of its original components are now obsolete, restoring SAM to its fully functional state is particularly difficult. With this project, we want to understand the possibilities presented by new technologies in 3D printing, and ultimately create a fully working replica of SAM without causing further damage to the original. A more traditional conservation approach would require invasive and risky handling, require new versions of its original components, and it would be unlikely that the sculpture would restored to full mobility. Modern 3D scanning technology means that a digital file can be produced without making contact with the original.

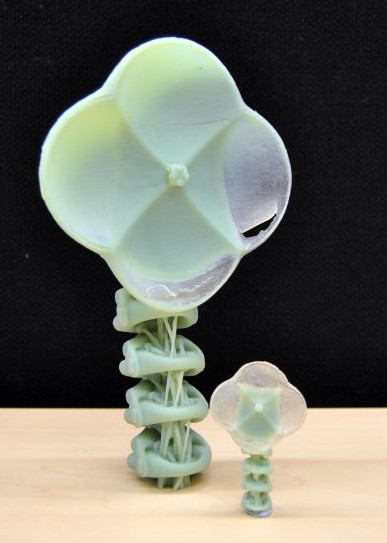

Recently, SAM was scanned by Sample & Hold, a 3D scanning company based in London (you can find a good description of the process here). This image was then taken to Middlesex University where a prototype was printed. The quality of the scans reproduced was quite remarkable, even picking up minute surface textures. However, one obvious issue for obtaining a historically accurate replica is that areas that could not be penetrated by the scanner (for example the inside surface of the vertebrae) can not be reproduced in the 3D digital image, and will possibly require laborious manual reconstruction.

So far, we have created a number of small-scale test prototypes of SAM. It’s our plan to create a full-size articulated version using the scan to print moulds from which cast aluminium vertebrae can be made, aswell as a fibreglass reflector, allowing a materially accurate copy of the sculpture to be constructed. This paves the way for the restoration of a fully responsive replica of SAM. However, given the fact that many of the electronic systems used 1960s are obsolete, getting SAM to interact and move as elegantly as he once did will be our challenge for the future.