Bravery and gallantry abound today as we celebrate the feast day of St. George: patron saint of England, Portugal, Germany, Lithuania, Georgia, Russia and Palestine, amongst others.

Through his portrayal in visual imagery this chivalrous saint has, perhaps, become most widely recognised as a dragon slayer. It is the representation of the dragon slayer that I will explore in this post looking at St. George alongside some of his comrades-in-arms including St. Michael the Archangel, St. Margaret, the Grecian hero Jason, and Sigurd (or Siegfried) from Norse mythology.

The stories and legends of dragon slayers have been used as a motif in art and design since antiquity. There are surviving examples of ancient Greek pottery showing famous heroes battling dragons including Jason fighting the Colchian Dragon and Cadmus killing the Ismenian Dragon.

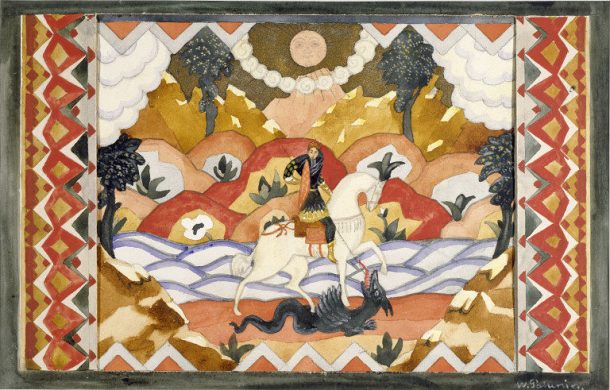

In the Word and Image Department, here at the V&A, we have a wealth of objects depicting imagery of dragon slayers ranging from medieval times to the 20th century. They are depicted in: medieval wall paintings and manuscripts; history paintings and prints after the paintings; illustrations to books; design motifs for furniture, jewellery and stained glass. They also, more specifically, appear in a design for a Russian theatre drop curtain, a British patriotic propaganda poster from WW1 and a photograph by Lewis Carroll of children acting out the story of George and the Dragon.

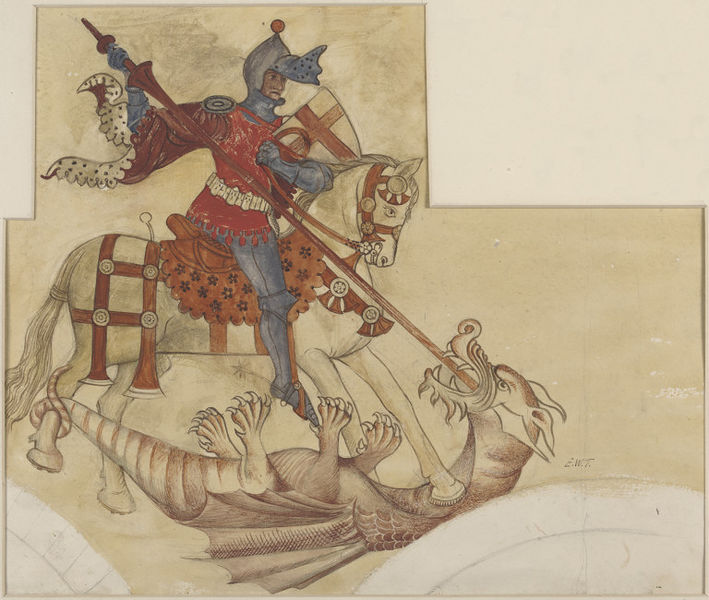

The depictions of the dragons are diverse and imaginative: they are often depicted as green, scaly, winged reptilian creatures, sometimes sinuous like snakes and other times stocky and strong like crocodiles, they are frequently illustrated with the heads and paws of lions and dogs, and occasionally have eagle-like heads. The appearance of the dragon slayer however is far less varied. If male the champion is usually depicted as either a gallant knight or a saintly hero dressed in armour and wielding a deadly weapon. The only exceptions to this are Hercules, who is often depicted nude, and St. Margaret, who is depicted differently through being female.

In myths and legends originating in Christian Europe dragons are typically symbolic of evil – this is why they are often being slain as it represents a battle of good over evil.

St. George is often seen as the most romantic and chivalrous of all the dragon killing heroes. This image stems from the medieval origins of the legend of St. George and the Dragon. During the middle ages there was a demand for chivalric romance – fanciful tales of the adventures of gallant knights often battling fearful opponents to save damsels in distress. This medieval chivalry was further romanticised by the Pre-Raphaelites who, rather than merely portraying the battle scene, produced episodic images to illustrate how St. George slays the dragon, falls in love and marries the Princess Sabra. He is mostly depicted in armour, often on horseback, slaying the dragon with a sword or long spear with the beautiful and passive Princess Sabra at the side-lines.

In the Book of Revelations St. Michael the Archangel battles with and defeats Satan in the form of a dragon in an archetypal example of good conquering evil. St. Michael is distinguishable from other dragon slayers as he is depicted with wings and usually has a halo.

St. Margaret is the most unusual of the dragon slayers in the collection as she is a woman! She is not shown in the throes of battle as the male heroes are nor is she depicted as chivalrous or gallant. Indeed in the episode telling of her encounter with the dragon she does not kill it through a violent act. After being consumed by the beast she defeats it, the tale tells, by making the sign of the cross which irritates its innards and makes the dragon disgorge her. She is often depicted, as in the image above, emerging unharmed and unflustered from the stomach of her defeated foe.

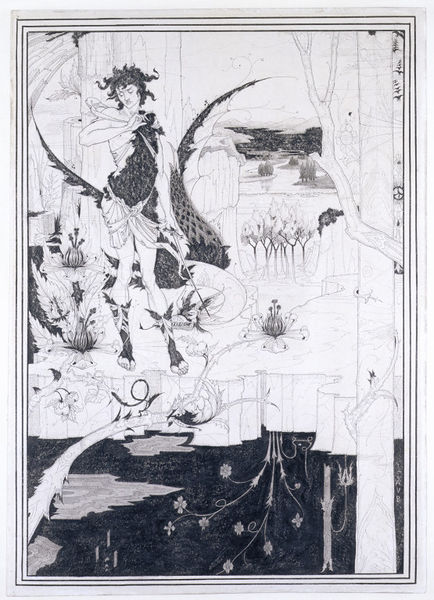

Fighting dragons is not always a battle of good over evil; sometimes they may be guarding precious or valuable objects that the hero desires and to acquire the treasure the slayer must kill the beast. This is the case in stories from ancient Greek and Norse mythologies. In order to reclaim his rightful throne Jason must bring Pelias, the imposter king, the Golden Fleece which is guarded by a dragon. Although Jason does not kill the dragon he does defeat it and takes the Golden Fleece. In the image above he is shown pouring a sleeping potion into the dragon’s eyes. Siegfried, from Norse mythology, is sent on a similar quest to reclaim treasure being horded by a dragon. The drawing below by Aubrey Beardsley shows the brave Siegfried standing beside a sinuous dragon with feathered wings.