No sooner had the new South Kensington Museum flung open its doors than its senior officers were agitating for additional space for the display of objects. In 1859, J. C. Robinson, the Museum’s first Superintendent of the Art Collections, complained in his annual report that ‘at the present time the nature and extent of the space given to this great national collection is entirely inadequate to its proper display and preservation, and equally unworthy of its intrinsic importance’.

By contrast, Henry Cole, the Museum’s first director, adopted a more conciliatory and practical strategy: as a senior civil servant he was doubtless looking for ways in which to make efficiencies. He was, however, no officious paper pusher but a highly original thinker who devised a novel space-saving solution for the display of museum objects, which he outlined in his report for the Sixteenth Report of the Department of Science and Art (1869):

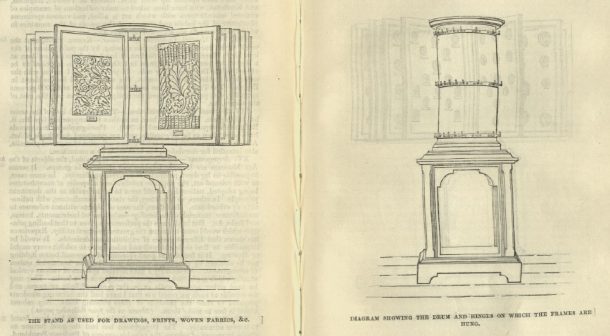

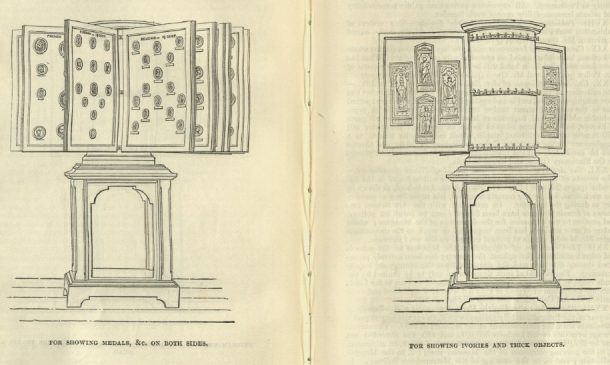

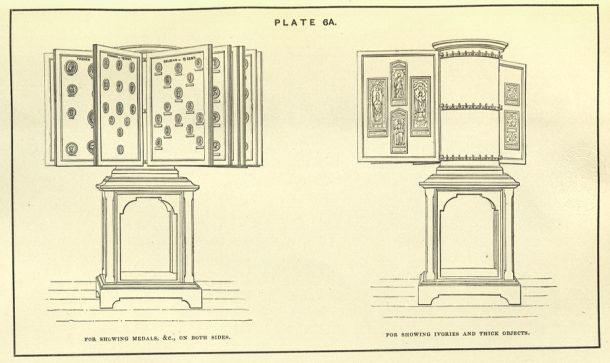

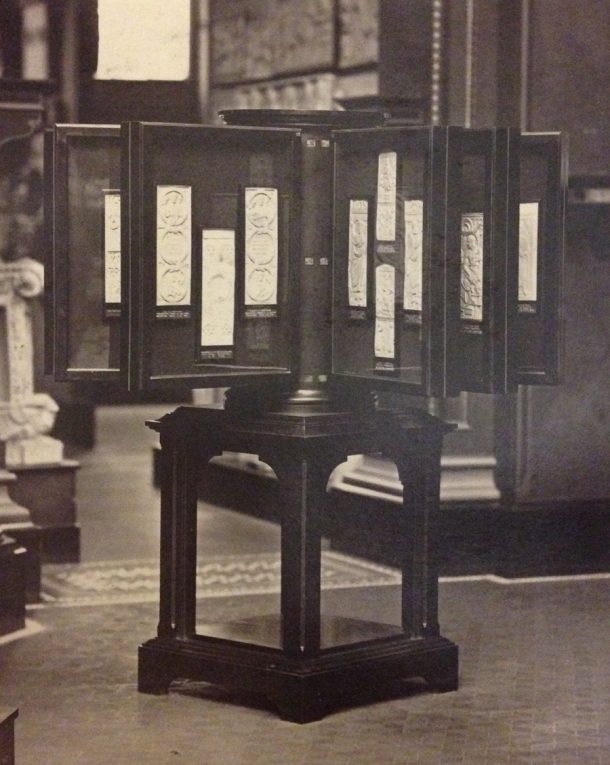

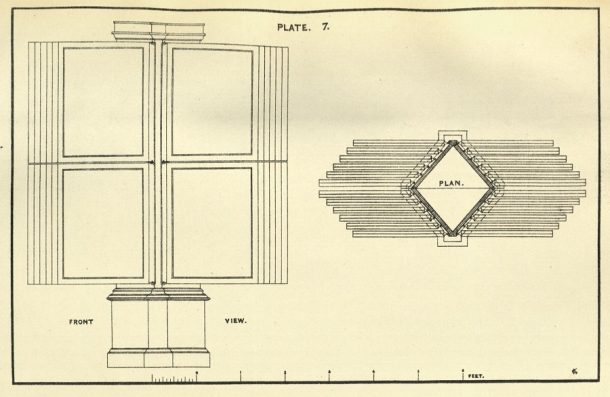

Experience has shown that different grades of exhibition are desirable. It would be impossible to find sufficient wall and other space to exhibit every medal or drawing. It is found that great economy of space and better lighting can be obtained by adopting a vertical instead of an horizontal system of arrangement. Accordingly I have devised a system of various vertical stands, which are in fact analogous to the leaves of a book. They may be used either against walls or in the centre of halls or rooms, and are capable of such universal use that I have had the following woodcuts prepared to show the principle of these rotating cases.

Cole had been working on a prototype for these experimental cases at least as early as 1866. His diary entry for 1 August makes reference to a visit to the carpenters’ shop to inspect ‘Radiating Pillar frames’, a description that seems applicable to the vertical stands. Rotating cases were in use in the Museum by December (Cole noted that they were admired by Lord Elcho, which implies novelty), although Cole neglected sadly to describe them in detail. The next year we find Cole hawking these cases at the Paris Exhibition (‘King of the Belgians went round the English Division … wished to have a radiating case’ and ‘Du Sommerard [Edmond du Sommerard, first curator of the Cluny Museum, Paris] wd take a Rotating Frame’). The printed Catalogue trumpeted Cole’s invention, and they were evidently pressed into service.

In any case (pardon the pun!), it is clear from Cole’s 1868 report that he intended his designs to be ‘open source’ (to use today’s parlance), that is, non-proprietary, available for reproduction and use beyond the confines of the South Kensington Museum: ‘Any cabinet maker is free to make them’, he declared.

Cole’s ambition for his vertical cases quickly grew into a larger commercial and museological enterprise which resulted in their repackaging in a standalone publication – Drawings of the glass cases in use for the exhibition of objects in the South Kensington Museum (1872). In his Preface Cole drew on his practical experiences of museum curation to extol the advantages of small cases. He was aware of the role that cases played in delivering a successful ‘visitor experience’ and to this end seems to have been an early advocate of a form of physical ergonomics:

The experience obtained at the South Kensington Museum has proved that small cases are much more convenient than large ones. They enable the Student to study the Specimens closely. Much space is saved. The Specimens are seen more effectively. When the cases have to be opened the risks of consultation are lessened. They can be re-arranged more easily than large cases.

A great difficulty in all Museums is want of space. Space is determined chiefly by the quantity of the floor space. By a judicious use of Vertical Space the floor space may be economized sometimes four fold. And the objects are better seen when the Spectator stands up, than when he stoops, a posture which may unpleasantly affect his head, inconveniences other Spectators, and takes up much room.

The Plates that followed were accompanied by detailed commentaries on the cases, which described their overall construction, types of objects they were intended to display, dimensions, including the equivalent area wall space offered by the frames, and retail prices. The rotating pillar case (Plates 6 and 6A), for example:

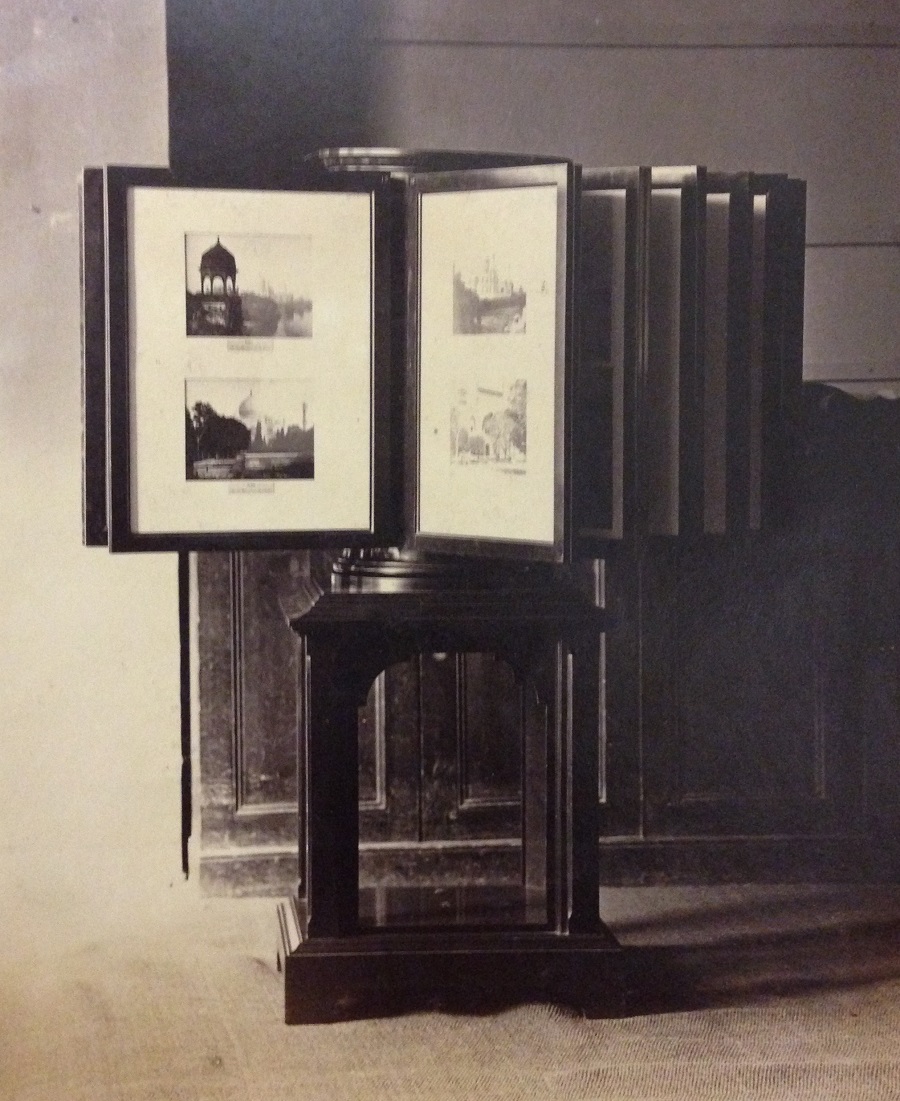

This is rotating pillar on a square open stand designed to exhibit series of many drawings, medals, etc. It is fitted with 30 pairs of imperial size frames (shewing 60 faces). The frames are connected together in pairs back to back by pianoforte hinges on the outside edges, and hung on pins projecting from the pillar, so as to open in somewhat the same way as the leaves of a book. The sight size of the frames is 2 feet 5 inches by 1 foot 9 inches, representing a total amount of wall space equal to 254 superficial feet. The whole of the woodwork is of the best Honduras mahogany stained black and ebonized. The pin rings are of gun metal with steel pins, the pin eyes are also of gun metal. The frames are glazed with Chance’s 21 ounce crystal sheet glass. Price, including frames, £73 10s.

I’m doubtful that Cole wrote these commentaries himself, particularly as he is explicitly credited with the occasional ‘aside’ that follows: ‘[A convenient case.—H.C.]’ and ‘[I consider that this [No. 7] accomplishes the same end as No. 6. It can be divided in the centre and each half place against a wall.—H.C.]’.

A new and expanded version of the catalogue was published in 1877. By this time, Cole had retired; however, I wonder for how long his vertical stands remained in use?

I’m trying to come up with an idea for displaying information at the Manx Museum and this is the closest to my idea that I could find. Thank you for writing about this and making the lovely images in your archive available.