The Utrecht-born goldsmith Christiaen van Vianen produced silver in a style associated with his father Adam van Vianen (about 1565 – 1627). The ewer in the Rijksmuseum made by Adam for the Guild of Amsterdam Goldsmiths in 1614 in memory of his brother Paul (about 1565/70 – 1613), Court Goldsmith to Emperor Rudolph, captures the liquid properties of the precious metal in sculptural form. Both brothers wrought silver with an artful balance between contour and plane, anticipating Rococo and Art Nouveau principles of design, and creating vessels that were first and foremost works of art.

Christiaen was the third generation of the family to practise the craft; apprenticed to his father Adam in 1616, he subsequently inherited the workshop and adopted his father’s AV monogram as his own personal maker’s mark, absorbing his father’s aesthetic and intellectual ideas. Christiaen published his father’s designs for silverwares in Amsterdam between 1646 and 1652. Raising such complex vessels from a single sheet of silver was a tremendous feat, as acknowledged in the portrait engraving of Adam van Vianen holding a goldsmith’s hammer.

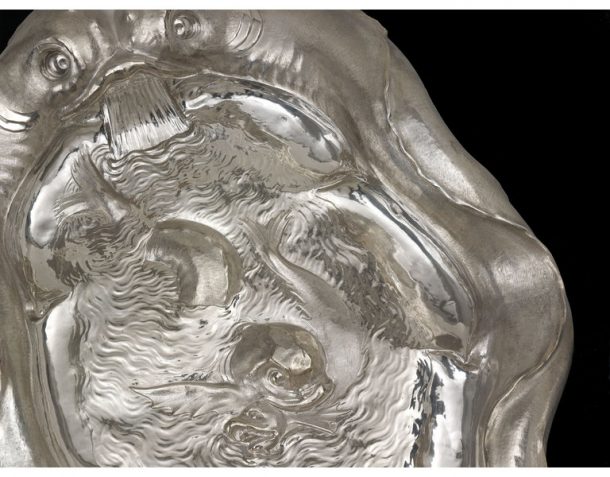

Christiaen’s 1627 drinking bowl, also in the Rijksmuseum, celebrates its function. The representation of water flowing into the bowl implies perpetual hospitality. When filled with actual liquid, the chased surface of the silver acts as a mirror or reflection, confusing the drinker with an optical illusion. The grotesque head that frames the cup, that of a mature male, is based on realistic observation. Father and son share the gift of raising living forms in silver which, through contrasting burnished and matt surfaces, offer an occasional reflective image of the drinker. The grotesque head serves as a warning of the dangers of drinking to excess.

Christiaen visited London in 1630, and attracted a royal pension from Charles I; £30 per annum. He returned to the British capital in 1632 and remained for 11 years, until political upheavals forced him to return to Utrecht. After the Restoration of the British monarchy, Christiaen van Vianen returned to London and re-established his workshop in Westminster. In 1663 he was appointed ‘silversmyth in ordinary’ to Charles II, a position he enjoyed until his death in 1667.

The fluid sculptural approach to silver design promoted by three generations of the van Vianen family had its origins in late 16th-century Northern European engravings inspired by ancient Roman ornament, known as ‘grotesques’ by Renaissance artists. Yet, this extraordinarily innovative style had an intellectual justification, Platonic in origin, that all metals were liquids that had congealed beneath the earth. The aqueous character of metals meant that they could be considered as living organisms – a perception reflected in the sinuous, sculptural forms created by this supremely talented family of craftsmen and their imitators.

The exact circumstances of the celebrated 1635 dolphin basin in the V&A are unrecorded. Given to the museum in 1918 by Sir John Ramsden, its history of ownership between 1635 and 1918 is untraced. The conventional form of a rosewater basin has been transformed into life-like sculpture; signed and dated ‘C.d.Vianen fecit 1635’ as a work of art. When not filled with rosewater, the craftsmanship can be admired from the back as well as the front. The recent trial filling of the basin with water, captured in film, demonstrates how effectively the basin could be used for the traditional purpose of rinsing the fingers in scented rosewater before and after the meal. The signature, date and lack of hallmark suggest that this may well have been a royal commission – although this is not documented. The silver was raised and embossed from a single sheet into brilliant, illusionist shapes that demanded extraordinary skill to make. The raised, wavy, undulating rim is formed as two dolphins whose heads come together on one of the short sides; water appears to stream from them into the dish. Among the waves on the bottom is another dolphin pouncing on a smaller fish.

The exchequer warrant dated 16 February 1636 for payment to van Vianen of £336.11s 6d demonstrates that Charles I commissioned a comparable ‘Bason & Ewer of silver … beaten wth the Hammer’ delivered on 14 June 1635, weighing 313 ounces. This is not the V&A’s dolphin basin (which weighs ’54-11’), but the museum’s masterpiece is indication of the quality of a royal commission that was melted down during the English Civil War.

nice updates