Arguably Art Deco – a term coined in the 1960s – isn't one style, but a pastiche of different styles, sources and influences. Art Deco designers borrowed from historic European movements, as well as contemporary Avant Garde art, the Russian ballets, folk art, exotic and ancient cultures, and the urban imagery of the machine age.

One of Art Deco's key sources was its forerunner, Art Nouveau, the fin de siècle style that fell out of fashion in the years before the First World War (1914 – 18). Key elements of Art Nouveau's visual language, such as plant and floral forms, were borrowed and adapted to create an updated vision, as seen in the stylised naturalistic fabric designs of the Atelier Martine.

The more linear, geometric variant of Art Nouveau, such as the work of Josef Hoffmann and Charles Rennie Mackintosh directly fed the Art Deco search for 'modern' forms and decorative motifs. Hofmann's two-handled bowl, a food vessel in gilt brass, with elegant curvilinear handles, inspired many silver designers of the 1920s.

Meanwhile, the arts of Africa and East Asia provided rich sources of forms and materials. Archaeological discoveries in the early 1920s fuelled a romantic fascination with early Africa and Mesoamerica. The excavation of Tutenkhamun's tomb in 1922 triggered a proliferation of Egyptian imagery such as lotus flowers, scarabs, hieroglyphics, pylons and pyramids. Read more about Art Deco's global influences.

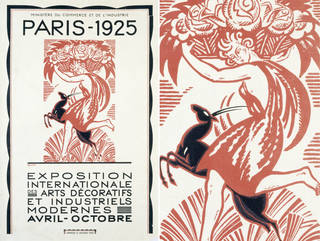

One of the most pivotal moments for Art Deco (known then as 'Style Moderne') was the Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes held in Paris in 1925.

The exhibition, dedicated to the display of modern decorative arts, brought together thousands of designers from all over Europe and beyond, including Emile Jacques Ruhlmann and Rene Lalique. Both designers were known for their exquisite detail and sense for quality. They became prominent promoters of the early Art Deco movement, putting their own modern spin on traditional craftsmanship.

As the 1920s advanced, many designers turned to the new visual language, colour and iconography of the Avant Garde. Movements such as Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, De Stijl, Suprematism and Constructivism – frequently bundled together under the label of 'Cubism' – were eagerly absorbed by designers seeking to capture the dynamism of the modern world. British and American critics often used the terms 'Moderne', 'Jazz Moderne' or 'Zigzag Moderne' to characterise such work. Geometric forms worked their way into all aspects of life, including everyday small items such as vanity boxes, cigarette cases, and tableware.

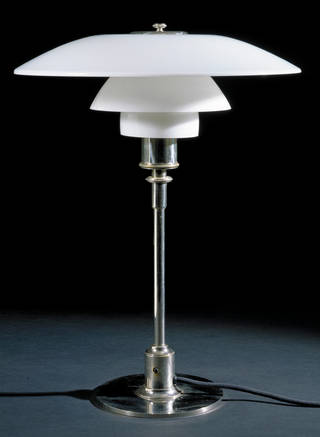

The stock market crash of 1929 saw the optimism of the 1920s gradually decline. By the mid 1930s, Art Deco was being derided as a gaudy, false image of luxury. By the outbreak of the Second World War, this hostility had become intense. Despite its demise, however, Art Deco made a fundamental impact on subsequent design. Its triumph is exemplified in Poul Henningse' PH lamp, manufactured by Louis Poulsen, which has been in continuous production with minor modifications ever since it was first introduced.

Art Deco's widespread application and enduring influence prove that its appeal is based on more than simple visual allure. Its strength comes from its willingness to embrace the duality of tradition and modernity, marrying luxury and function in a versatile way. These qualities and characteristics can be enjoyed, in their many guises, throughout our collections, from fashion to furniture.