Circuses have been a popular form of entertainment for centuries, but their acts have changed greatly over time. The V&A holds in its collection a large number of objects that reveal the fascinating history of the circus.

Philip Astley (1742 – 1814), a six-foot tall, ex-cavalry man, is often credited as the 'father of the modern circus'. In 1768, he and his wife Patty established Astley's Riding School in London, where Philip would teach in the morning and perform equestrian tricks in the afternoon. Both Philip and Patty were expert riders. Philip's most famous act and widely considered to be the first circus clown act, was ‘The Tailor of Brentford or ‘Tailor's Ride to Brentford’, in which he acted out a comic journey on horseback. One of Patty's popular tricks involved her circling the ring on horseback at speed, with swarms of bees covering her hands and arms as if she was wearing a muff.

Astley is also credited with discovering that the ideal size for a circus ring is 42 feet in diameter. This was the optimum size that enabled him to use centrifugal force to help balance on a horse's back. As he rode at speed around the ring, he used gravity to push himself into the horse's back and so prevent a fall onto the sawdust floor.

Astley quickly began to incorporate other acts from the fairs and pleasure gardens of London and Paris into the performance. These were acrobats, jugglers, rope dancers, clowns and strongmen. By 1780 he had built a roof over the entire arena so that his audiences could enjoy performances throughout the whole year.

Astley may have been credited as the 'father of modern circus' but it was his rival Mr Charles Dibdin (1745 – 1814), British composer, musician, dramatist, novelist and actor, who first coined the word 'circus'. Dibdin copied Astley's formula of dramatic equestrian entertainment by opening The Royal Circus a short distance from Astley's Riding School.

In 1795, Astley opened the Royal Amphitheatre after his previous building had burnt down. The Royal Amphitheatre had a stage in addition to the circus ring and the two were interlinked by ramps. This was an ingenious design, which heightened the possibilities for tricks and dramatic effect. The audience could sit close to the ring with horses swishing past their faces as they cantered up a ramp just a few inches away. But in 1803, disaster struck again as the wooden building, lit by candles, burnt down.

In 1804 Astley's was rebuilt for a third time. Each time the theatre was rebuilt the interior became more ornate. Astley also ensured that the stages were strengthened to take the weight of more horses and increase the dramatic potential of his acts. He continued to collect new acts from home and abroad with clowns, ropewalkers and tumblers complementing the equestrian entertainment.

In 1824 the management of Philip Astley's Amphitheatre was taken over by the circus performer and 'father of British circus equestrianism', Andrew Ducrow (1793 – 1842). Ducrow staged popular equestrian dramas such as Mazeppa; The Courier of St Petersburg and Ivanhoe. These were huge spectacles involving scenery changes, beautiful costumes and dramatic theatrical effects such as the imitation of thunder. Ducrow was an excellent trick-rider but also proficient as a tumbler, ropedancer and theatre actor. Born into a circus family in Southwark, London in 1793, Ducrow was trained in circus skills from a very young age. His father was an acrobat and strongman who could reputedly carry five children on a table using no more than his teeth. At the age of 19, Ducrow had appeared at Astley's with an act called 'The Flying Wardrobe', in which he would speed around the ring on horseback dressed as a drunkard in rags. After many false falls and the removal of several waistcoats he would reveal himself as the star rider of the show. This act is still performed in many circuses today as a comic 'entrée' or opening.

In addition to equestrian dramas, the audiences at Astley's were also kept up to date with topical events. News from the Napoleonic Wars (1803 – 15) were presented in dramatic form using exciting horse displays. In 1853, Astley's also presented The Battle of Waterloo and The Battle of the Alma. The following year William Cooke produced The Crimean War. This show suffered an unfortunate first night when many of the actors were injured from the gun fire despite the use of fake ammunition. Cooke had to pay out almost as much in compensation as he could hope to take in profits.

Victorian circus

In the mid-19th century there were hundreds of circuses operating in Britain. Trick-riding continued to be the main attraction, but a variety of other acts developed, including an aquatic circus where the circus ring was flooded with water. Such was the popularity of circuses that many 19th-century theatres also presented circus acts and you were as likely to see jugglers and aerial acts on a trip to the music hall as at a circus. Circus was a hard business, and whilst some circus owners such as George Sanger made their fortune, many died penniless.

One of the factors that made circus so popular was that fairground entertainers travelled to their audiences. From the late 18th century, circuses toured to even the smallest towns and in the 19th century the development of the railways enabled circuses to travel further. By the 1870s huge circuses were touring across Europe and America with two or three trainloads of equipment. Astley's Circus toured regularly throughout Britain as well as visiting Paris and other European cities, despite the often difficult travelling conditions.

Richard Sands was an American circus owner as well as an acrobat, equestrian and 'ceiling walker'. His Sand's American Circus first visited England in 1842 with a stud of 35 horses and 25 equestrians. Sands presented his 'air walking' act, using rubber suction pads attached to his feet, at the Surrey Theatre and later at Drury Lane in 1853. In 1861 however, the stunt ended in disaster. He was challenged to walk across the ceiling of a civic building in Melrose, Massachusetts in the United States but when a section of plaster he was attached to gave way, he was killed by the fall.

Richard Sands is credited with introducing the type of tent we associate with circus today to England. Sand's American Circus was advertised as having a "splendid and novel Pavilion, made after an entirely new style". Sands' Circus toured England for three or four years, and his tent was enthusiastically imitated.

Early touring circuses were often small operations, manned entirely by a single family. The company might include a couple of acrobats, a clown who performed a comic equestrian act, a tightrope walker, and as many horses as could be afforded – perhaps two trained to perform and two used to pull the cart from town to town. A short show would be repeated several times a day from noon until night, with an audience stood watching from behind a wooden barrier. All the performers had to play several parts, and in the days before the enclosed circus, the company would pass around a hat to collect money from the audience.

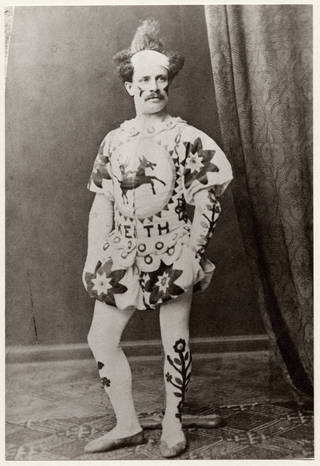

In 1892, Charlie Keith (1836 – 95), famous clown and circus owner, constructed and patented the first portable circus building. Keith had made his name touring in circuses around the UK and Europe. He was frustrated with performing in leaky tents with slippery and muddy floors and wanted to construct a touring circus that was sturdier than canvas.

Keith's portable circus was made of planks of wood nailed together and a canvas roof that could be flat packed onto transportation. The building even had its own box office. It was illuminated with gas lights and advertised as having a 'grand promenade with a fashionable lounge'. Keith claimed that his 'circus building on wheels' or 'Keith's Carriage Circus' was an innovation, but he was not the first to have the idea, with similar arrangements having been advertised for sale as early as 1854.

Temporary circus buildings, which many companies used in the early 19th century, were often hastily built and unsafe. The gallery of a Bristol circus fell down in 1799, and in 1848 the wife of the circus proprietor Pablo Fanque was killed in Leeds when the pit and gallery of a temporary wooden circus collapsed.

Circus parades

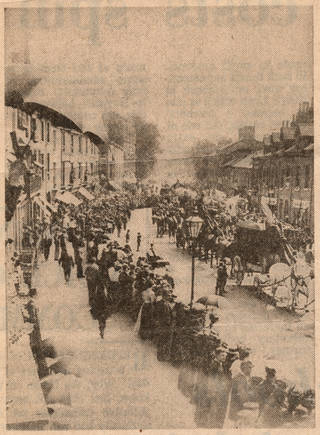

Larger circuses would often announce their arrival in town with a circus parade. The parade was a natural advertisement for the circus and would attract huge crowds. Barnum and Bailey's Circus parade along the Prince of Wales Road in Norwich in 1899 included a menagerie, a military band, 70 horses and collection of 'living human curiosities'. During the parade a '40-horse hitch' (a wagon pulled by 40 horses) damaged the front of a pub called The Mayflower. The resulting publicity more than made up for the expenses incurred by the owner, and he renamed the pub the Forty Horse Inn.

When Sanger's Circus arrived in town in the late 19th century, it did so in style. A typical carriage weighed ten tons and was drawn by four horses in 'royal state harness' as part of a grand procession. All the carved woodwork on the carriage was gilded. Sanger's wife, Mlle Pauline de Vere, sometimes dressed as Britannia and rode on top of a carriage holding a Union Jack shield, a gold trident, and wearing a Greek helmet. The circus lion, Nero, and a lamb sat together at her feet. After this came a string of camels, a herd of elephants, numerous other costumed characters, exotic animals either in cages, or led by their trainers, and of course, the band. During the Second World War, the gilt on the carriage was scraped off and sold, and Sanger was forbidden by the authorities to clog up the roads with his spectacular, but slow moving processions.

'Lord' George Sanger (1825 – 1911) was the most successful circus entrepreneur of the 19th century. An eccentric millionaire, notorious for being a smart dresser, Sanger was instantly recognisable by his shiny top hat and diamond tie pin. Sanger had started in business at the age of 15 selling sticky rock confectionery. In 1853, he opened a circus with his brother, which toured the country. By its 1855 tour to Liverpool, Sanger's Circus was playing in front of large audiences. Soon after this, Sanger introduced lions and other wild animals into the touring circus, which boosted its popularity further. By 1871 Sanger was so successful he was able to buy Astley's Amphitheatre. His circuses continued to tour the country and he boasted that there was not a town in England with a population above 100 people that had not been visited by a Sanger's circus.

20th-century circus

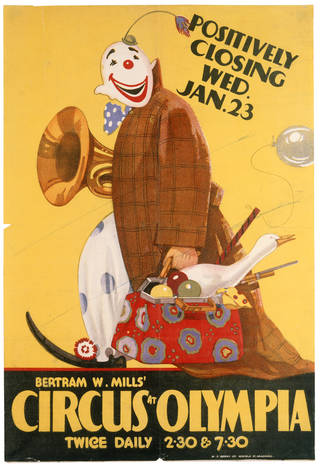

One of the biggest names in circus history was Bertram Mills International Circus. Bertram Mills (1873 – 1938) formed his circus having made a bet with a friend that he could set up a successful circus company within 12 months. On 17 December 1920, Mills opened a 16-act show at Olympia in West London for the Christmas season. Although Mills had no direct experience of working in circus, like Astley before him he was a keen horseman and had travelled to horse shows in Europe and America and realised the potential to reinvigorate circus in Britain. Mills had the foresight and vision to create an international circus, bringing the most exciting acts from all over Europe to Olympia, including Japanese gymnasts and trick-cyclists from the Swedish circus owner Henning Orlando. The circus was a huge success and Bertram Mills International Circus became a household name in the UK for its annual Christmas shows that ran until the 1966 season.

Mills was an astute businessman and realised that in order to profit from the circus he would have to sell seats at a higher price than was customary. To try to attract a richer audience he instigated 'opening lunches', inviting as many influential people as he could muster, including members of high society and key members of the press. By 1927 the prestigious guest list included Sir Winston Churchill and his wife, politician Ramsay McDonald and the Earl and Countess of Orkney. His innovative and high profile advertising campaign paid off. The press billed the Olympia performance as "The Great Circus Revival".

Every season at Olympia the Bertram Mills' Circus had two dress rehearsals on the day before opening. Each rehearsal was attended by children from poor families, who were chosen by the Mayors of the London Boroughs. They not only saw the show, but were treated to refreshments during and after the performance. Between seven and ten thousand children were invited to a pre-Christmas rehearsal every year.

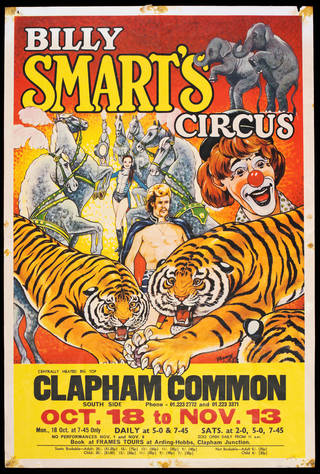

When Mills retired, his sons continued to develop his circus, bringing new acts from across Europe and America. They also continued to tour Bertram Mills' Circus across the UK and soon other travelling circuses followed: Chipperfields, Billy Smart's, the Robert Brothers', Bobby Robert's Circus, Cottle and Austen's, Gerry Cottle's, and Zippo's. In the 1950s and 1960s a trip to the circus was still an eagerly anticipated treat for millions of British schoolchildren.

Circus acts

From clowning and ballooning, to menageries and trick-riding, explore some of the circus acts that have entertained audiences over the last 250 years.

The decline of traditional circus

The popularity of traditional circus in the UK has waned in the last 50 years. Gone are the magnificent circus parades to announce the arrival of a circus in town. No longer do great trains carry circuses across the country by night. Gone too are the wild animal acts, sideshows and menageries.

In the 1960s and 70s television began to show natural history programmes and people began to question the use of animals in the circus. Safari parks, a phenomenon of the same time period, also enabled people to see wild animals in more natural surroundings. People were no longer as thrilled and amazed to see lions and tigers in the circus ring as their 19th century ancestors.

Many circuses today however, still feature equestrian acts – the skill that encouraged Philip Astley to start the first circus in London over two hundred years ago. There are now fewer than 20 circuses in Britain today. The circus owners who continue the tradition are constantly aiming to find new ways of attracting the public with increasingly ambitious staging of their shows.

Circus reinvented

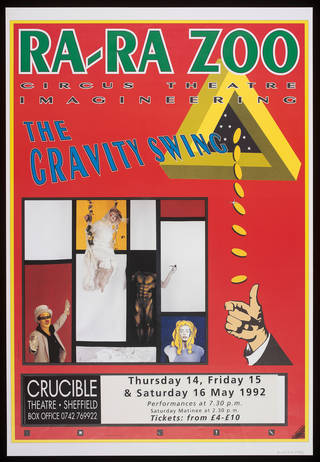

Whilst traditional circus may be in decline, alternative circuses, such as Circus Oz, Cirque du Soleil, Ra Ra Zoo and Archaos have drawn on traditional skills and presented them in a more contemporary style. Gerry Cottle's 'Circus of Horrors', is billed as a 'darkly comical show', and presents circus skills in a more theatrical framework.

Despite the decline of traditional circus, new circus schools have opened in the UK to train performers in a variety of tricks, from aerial acts to juggling. In 1983 Gerry Cottle set up Britain's first circus school, which offered students the opportunity to tour with professional companies as part of their training. In 1989, The National Centre for Circus Arts opened in London as a centre for training in contemporary circus skills, teaching tumbling, trapeze, acrobatics, and juggling.