James 'Athenian' Stuart (1713 – 88) is a compelling figure in the history of British design. Widely recognised for his central role in pioneering Neoclassicism, Stuart developed his influential career across the various fields of interior decoration, sculpture, furnishing, metalwork and architecture.

The creation of the 'Greek Style' and its impact on British design in the late 18th century is largely due to Stuart's landmark publication Antiquities of Athens (1762). This influential book was the first accurate record of Classical Greek architecture and served as a principal source book for architects and designers well into the 19th century.

Early years and artistic training

James Stuart was born in London in 1713, the son of a Scottish sailor, whose death left his young family in poverty. A talented artist even as a child, Stuart was apprenticed to a fan painter. In about 1742 he set off on foot to Italy, intent on improving his artistic skills. Here Stuart worked as a painter and guide to antiquities while studying art and architecture, and also learning Italian, Latin and Greek. A major work during these years was his De Obelisco, an illustrated treatise on the Egyptian obelisk of Psammetichus II in Rome.

In 1751 Stuart and his friend Nicholas Revett visited Greece to measure and record antiquities. Detailed scholarly studies of Roman ruins already existed, but the attempt to apply the same approach to Greek remains was new.

Antiquities of Athens

After his return to London in 1755, Stuart worked on the first volume of Antiquities of Athens, which was published in 1762. He wrote and revised the text, had the illustrations engraved, and designed a binding. The first volume contained details of just five buildings in the northern part of Athens, but more were promised in further volumes.

The first volume had more than 500 subscribers. Few were architects or builders, which limited the impact of the work as a design sourcebook. It was, however, well received by scholars and students. The presentation binding that Stuart designed for Antiquities of Athens inspired the architect Robert Adam to design similar presentation bindings for his work on the antiquities of Spalatro in Split, Croatia.

Antiquities of Athens helped shape the European understanding of ancient Greece. It brought an entirely new design vocabulary to 18th-century European architecture and design, and later became an essential sourcebook for the 19th-century Greek Revival.

Country houses

Stuart's work as an architect grew out of his reputation as a painter, connoisseur and authority on Greece. Wealthy patrons employed him for his skill as a designer but also for his judgement in matters of taste.

He only built one complete country house, Belvedere in Kent. Instead, most of his work outside London consisted of alterations to existing houses and villas. Villas were compact buildings near large towns, used by their fashion-conscious owners for hospitality and display. For these projects, Stuart drew on his first-hand experience of Greek and Roman remains to design some of the earliest Neoclassical interiors in Britain.

Furnishings

For many of these commissions, Stuart designed furniture and metalware. These were eclectic in design – fusing Baroque forms with elements taken from early French Neoclassicism. They also included direct copies of Greek and Roman ornament and furniture types.

One of Stuart's most important and enduring designs is the tripod perfume burner. It is based on his sketch of the tripod that once stood on the roof of the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens. On his return to London, Stuart revived this tripod form, which appears as a decorative object in his drawings, dating from as early as 1757. Tripods would become a standard part of the Neoclassical style, but this one by Stuart appears to be the first made in metal since ancient times.

The seating Stuart created for the Painted Room at Spencer House, London – built between 1756 – 66 for John, first Earl Spencer – combined elements from a wide variety of sources. The animal-leg supports for both the armchairs and the settees derived from ancient seating forms. The settees were among the earliest Neoclassical style furniture in Britain.

Garden buildings

More than a third of Stuart's architectural commissions were for garden buildings. His career coincided with the development of the Picturesque in garden design – a style inspired by the romantic landscape paintings of French artists such as Claude Lorrain and Nicholas Poussin. Views were vital to the Picturesque aesthetic. Buildings and follies provided focal points within the design, and views to and from them were carefully composed.

As Stuart had visited Greece in person, he was able to provide a stamp of authenticity, unavailable to other architects, when designing structures derived from classical antiquity. Many of Stuart's garden buildings were copies of structures he had measured in Athens, while others display his versatility and eclecticism, incorporating sources outside the limits of the 'Greek style'.

Town houses

In the 18th century, rich families increasingly spent part of the year in London. The houses that they built were not merely spaces for living, but also an opportunity for entertaining and display. Their lavish interiors were an expression of taste and education as well as wealth.

Stuart's reputation as a man of learning and an authority on classical art and design enabled him to exploit the opportunities that arose in this flourishing market. He provided interior designs and built town houses, using Greek architectural elements that had never been seen before by the London public. Some examples of his work, include the interior furnishings and exterior of Lichfield house at 15 St. James's Square, London.

Public commissions

Stuart undertook several commissions that could be described as public works: for the Crown, the Admiralty and at the Royal Hospital for Seamen at Greenwich, where he held the post of Surveyor from 1758. Much of the ornament and decorative detail for these public buildings came from Greek public architecture such as temples, amphitheatres and monuments. Stuart had already successfully incorporated these classical elements into his domestic interiors, but they were at their most spectacular when used on a large scale, as in The Chapel of St. Peter and St. Paul, Old Royal Naval College, Greenwich. Public buildings like the chapel, by their very nature, helped spread the Neoclassical style to a larger audience.

Medals

James Stuart designed at least 20 medals, many for the Society for the Promotion of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, also known as the Society of Arts. Stuart and his patrons used the design of these medals not just to promote patriotism, but also as a propaganda tool to influence public opinion and advance a particular political agenda. Adapting the imagery of classical coinage to celebrate British military, artistic and scientific accomplishments, Stuart made an explicit visual link between the achievements of the Roman and the British empires. This was especially the case with the series of medals commissioned by the Society of Arts to commemorate British victories during the Seven Years' War – the global conflict fought between 1756 and 1763.

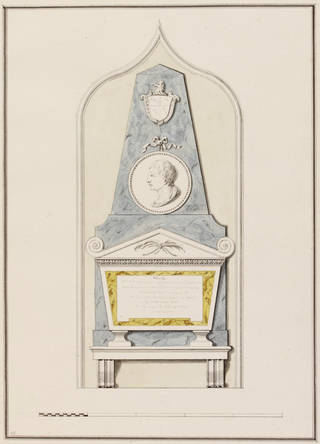

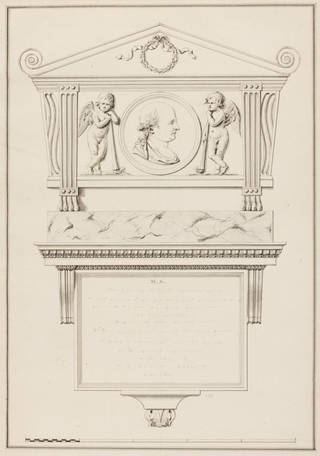

Monuments

In his designs for memorials and monuments Stuart used many of the traditional motifs of 18th-century funerary art, such as sarcophagi, portrait busts, grieving women, putti (chubby male children) and obelisks (tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monuments). He was innovative in being one of the first designers to use low-relief portrait medallions in monuments instead of the more customary portrait busts.

In his monument designs, Stuart worked closely and almost exclusively with the father and son sculptors Peter and Thomas Scheemakers. This collaboration took place at a time when the standing of stone carvers was rising, and individual sculptors were beginning to lay claim to the status of artists in their own right. The Scheemakers exploited their alliance with Stuart to enhance their own reputation. The next generation of sculptors also owed Stuart a debt. Antiquities of Athens had made available a vast collection of classical ornament, which sculptors could use without the intervention of an architect or designer.

Later years and legacy

From the late 1760s complaints began to surface about Stuart's increasingly chaotic business practices, which were possibly due to his chronic gout and deteriorating health. The problem worsened, and by the early 1780s even his friends noted that he spent his afternoons drinking and playing skittles rather than attending to business.

However, Stuart continued to work intermittently and also returned to the Antiquities of Athens. This was unfinished at the time of his death in 1788 and the final volume only appeared in 1816, when the Greek Revival style was beginning to dominate British architecture. Stuart's London buildings had played a role in the propagation of Neoclassical taste, but it was the Antiquities of Athens that had the greatest impact. As a sourcebook it influenced architects, sculptors and designers in Europe and America for the next two centuries.