Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) was an Italian Renaissance architect, musician, inventor, engineer, sculptor, and painter. He is widely considered to be one of the greatest painters of all time and perhaps the most diversely talented person ever to have lived. His notebooks contain diagrams, drawings, personal notes and observations, providing a unique insight into how he saw the world. Five of these incredible objects are in our collection.

Leonardo seems to have begun recording his thoughts in notebooks from the mid-1480s when he worked as a military and naval engineer for the Duke of Milan. None of Leonardo's predecessors, contemporaries or successors used paper quite like he did — a single sheet contains an unpredictable pattern of ideas and inventions — the workings of both a designer and a scientist.

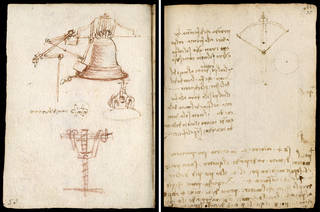

The notebooks contain careful sketches and diagrams annotated with notes in 16th-century Italian mirror writing, which reads in reverse and from right to left. The mirror writing has caused much speculation. Was Leonardo trying to ensure that only he could decipher his notes? Or was it simply because he was left-handed and may have found it easier to write from right to left? Writing masters at the time would have made demonstrations of mirror writing, and his letter-shapes are in fact quite ordinary: he used the kind of script that his father, a legal notary, would have used. It is possible to decipher Leonardo's curious mirror writing, once the eye has become accustomed to the style.

Leonardo probably worked on loose sheets of paper (bought at one of Milan's many stationers' shops), which he carried about with him to record his observations. His papers were at some stage folded into booklets and later bound, possibly under the ownership of the Spanish sculptor Pompeo Leoni (1533 – 1608). The five notebooks in the V&A's collection are bound into three codices (a bound book made up of several pages) called the Forster Codices, after John Forster who bequeathed them to the Museum in 1876. The codices are not bound in any logical order and only one, Codex Forster I.1, carries any indication of when it was made.

You can explore all three of our Forster Codices in amazing detail by following the links under each codex section

Codex Forster I [containing Codex Forster I.1 & I.2]

Codex Forster I.1 (up to folio 40, Florence, 1505)

A note in Leonardo's own hand gives this notebook a title, Libro titolato de strasformatione, and dates it to July 1505. This shows that it was begun when he was in Florence, just after he had undertaken to produce his famous Battle of Anghiari mural in the Palazzo della Signoria, the centre of the city's government. The notes consider the measurement of solid bodies and the problems of relating changes in shape to those of volume, a branch of mathematics known today as topology.

Codex Forster I.2 (from folio 41, Milan, about 1487 – 90)

The earliest of the V&A's notebooks, it was compiled around 1487 – 90 when Leonardo was a servant of the Sforza duke in Milan. The writing on a few sheets of this notebook extends beyond the inner margins, suggesting that Leonardo wrote them before the sheets were folded into the booklet as it survives today. It contains notes and diagrams for devices relating to hydraulic engineering and on the moving and raising of water. Leonardo was renowned for designing elaborate devices for entertaining guests at courts and in noble houses, particularly water clocks and fountains. One design, for the French governor of Milan, was elaborately automated, with a mechanical man as a bell-ringer.

You can explore the complete Codex Forster I, and in amazing detail, in our page viewer by following the link below.

Codex Forster II [containing Codex Forster II.1 & II.2]

Codex Forster II.1 (up to folio 63, Milan, about 1495)

This notebook was compiled around 1495. It contains notes on the theory of proportions and mentions the work of Leonardo's colleague in Milan, a famous mathematician named Luca Paccioli (died about 1514). It also contains a good deal of miscellaneous material: bells and a striking mechanism, a portrait of the General of the Franciscan Order, Francesco Nanni-Samson, and a passage discussing the postures of a group at a table, possibly relating to Leonardo’s work on the Last Supper fresco in Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, begun in about 1495.

Codex Forster II.2 (from folio 64, Milan, 1495 – 97)

Made up between about 1495 and 1497, Codex Forster II.2 has extensive notes on the theory of weights, traction, stresses and balances. It also contains an examination of a crossbow (a terrifying weapon outlawed on several occasions by the Pope), and a remark ridiculing those who thought perpetual motion was possible.

Some of the ideas recorded on the page below investigate perpetual motion — the concept of a hypothetical machine which, once activated, would run forever, like a wheel which never stops turning. Leonardo made several thorough studies of perpetual motion, though eventually rejected the theory.

You can explore the complete Codex Forster II, and in amazing detail, in our page viewer by following the link below.

Codex Forster III

Codex Forster III (Milan, about 1490 – 93)

This is the most miscellaneous of the notebooks. Interspersed with notes on geometry, weights and hydraulics are sketches of a horse's legs (perhaps connected with Leonardo's work on an equestrian statue for the founder of the Sforza dynasty), drawings of hats and clothes that may have been ideas for costumes at balls, and an account of the anatomy of the human head. Leonardo made frequent dissection drawings of both humans and animals, contributing to anatomical and physiological discovery.

You can explore the complete Codex Forster III, and in amazing detail, in our page viewer by following the link below.

These five notebooks, bound into three volumes, are in the collection of the National Art Library

One is currently on display in the Medieval & Renaissance galleries, Room 64