Photography Centre

The largest space in the UK dedicated to a permanent photography collection

The largest space in the UK dedicated to a permanent photography collection

Introducing the photography collection

Take a behind-the-scenes look at our world class photography collection following the transfer of the Royal Photographic Society (RPS) Collection

Take a spectacular journey through the history of nature photography

Find out about the processes and techniques used to create the photographs in our collection

Discover the many faces of Lee Miller – an incredible photographer, surrealist artist and war correspondent

Take a journey through some of our quirkier nature images

Colour photography at the V&A

Explore our vast and varied collection of colour photographs

A brief history of ghosts and spirit photography

Find out about the Victorian obsession with seances, spiritualism and capturing ghosts

Maud Sulter's powerful photographic portraits celebrate the cultural achievements of Black British women

Take a photo with a Victorian sliding box camera: ASMR

Watch and listen as we demonstrate how it would have been used

Cameraless photography

Discover this experimental, radical and often revelatory form of vision

The circus photography of John Hinde

The power of photography to create a "greatness and fullness of life"

Staying Power: Photographs of Black British Experience

Staying Power aims to raise awareness of the contribution of black Britons to British culture and society, as well as to the art of photography

Linnaeus Tripe: life and work

Find out more about the pioneering 19th-century British photographer

A brief history of vampires – in print, photography and posters

Discover, if you dare, how Count Dracula haunts the V&A's collections

Off Pointe by Mary McCartney

'Off Pointe' by Mary McCartney captures intimate moments of Royal Ballet dancers behind-the-scenes

The puzzle of portraits: Francis Williams and Vanley Burke

Explore two important portraits separated by three centuries

Alfred Stieglitz – pioneer of modern photography

"Photography fascinated me, first as a toy, then as a passion, then as an obsession."

Shooting Concorde

Photographer Hélène Binet captures the iconic Concorde on film

The camera as star

Photographs curator Marta Weiss turns the focus on the camera itself with 10 highlights from the Camera Exposed display

Cecil Beaton: royal photographer

Find out more about the Cecil Beaton archive of royal portraits at the V&A

Cecil Beaton – an introduction

A photographer of fashion, society, and the British Royal Family, Cecil Beaton was also a set and costume designer and fashion expert

Horst P. Horst – an introduction

The idealised figures and spot-lit style of Horst's images shaped the way fashion was presented in the 20th century

Paul Strand – an introduction

Martin Barnes, senior curator of photographs at the V&A, discusses the significance of Paul Strand's work

Curtis Moffat: life and work

Curtis Moffat captured the 'bright young things' of the roaring twenties in stunning photographic portraits

Curtis Moffat: working methods

Discover how Curtis Moffat created balanced, interesting compositions that play with light and shade

The making of an iconic image: Christine Keeler, 1963

A political scandal, a chair, a photograph. Discover the making of an iconic image.

Horst at work: behind the scenes at American Vogue

Original film footage from the Vogue cutting room floor gives a fascinating insight into the history of fashion publishing

Surrealist photography

Discover strange shapes, floating body parts and bizarre landscapes...

Tim Walker's love letter to the V&A

We joined Tim Walker on some shoots for his latest project...

Benjamin Brecknell Turner – an introduction

Discover one of the earliest, and greatest, British amateur photographers

The real Alice in Wonderland

Meet Alice Liddell, Lewis Carroll's muse and inspiration

Wonderful Things: the making of an exhibition

Hear how the magical Tim Walker: Wonderful Things exhibition took shape

Lady Clementina Hawarden – an introduction

Discover a prolific yet enigmatic early photographer

Real Beauty: photography by Jodi Bieber

Photographer Jodi Bieber invited women to pose in their own homes, dressed in their underwear, for her series Real Beauty

Grace Robertson: life and work

Grace Robertson was a pioneering photographer who captured the every-day lives of British women

About the Known & Strange display

Discover some of today's most compelling achievements in contemporary photography

Maurice Broomfield – an introduction

Meet Britain's premier industrial photographer

Talking photography: Maurice Broomfield

Listen to Britain's premier industrial photographer talk about some of his most iconic work

100 years of fashion photography

Discover the key trends in fashion photography over the last 100 years

Studio, street and style: the photography of James Barnor

Meet the pioneering portrait photographer James Barnor

Julia Margaret Cameron – an introduction

Introducing Julia Margaret Cameron, one of the most celebrated women in the history of photography

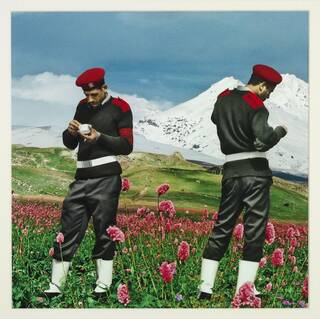

Photographing masculinities: gender, identity and the gaze

Look through the lens of female and non-binary photographers in our collection

Clicking the shutter on Paneth's plate camera: ASMR

Experience the camera like photographer Friedrich Paneth would have done

Photographing the 'Great Eastern'

Discover Robert Howlett's iconic photographs of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and the ill-fated 'Great Eastern'

Family, photography, memories: Africa Fashion

Find out about the personal stories and unique fashion histories from individuals across the continent

Listen in as we set it up

In an era of smartphone cameras we can all take photographs, but what makes an image 'great'?