Unlike women's clothing, European men's garments, from at least the Renaissance onwards, had numerous sewn-in pockets in their coats, jackets, waistcoats and breeches. The low survival rate of women's garments from this period makes it difficult to establish precise dates but tie-on pockets were certainly in common use from about 1650 to the end of the 19th century, and some even later. Even when different types of bags and 'male-style' pockets were available to women, the tie-on pocket remained enduringly popular and surprisingly stable in its design.

Pockets could be easily and rapidly made of almost any available pieces of durable fabric, including leather. It was popular to use either plain linen or, as many women chose to do in the 18th century, embroider them in silks or wools. In doing this, they worked with variations of long-established floral decorative schemes but often added personalised motifs or their initials.

These highly functional pear-shaped pockets, typically featuring a vertical opening, were worn either singly, in pairs, or sometimes in threes, and were tied around the waist independently of clothing. They were accessible through openings in the dress and petticoats.

Surviving pockets reveal they were generally quite big – many were 40cm long and 30cm wide – meaning that they could contain a lot of possessions. Tie-on pockets were highly practical options for mobile women, giving them both flexibility and offering convenience for the wearer – another reason for their ongoing popularity. In polite society, formal situations, or when travelling, pockets would normally be invisible under a woman's petticoats, but for working women they might be more visible and immediately accessible, worn just under an apron. Ever versatile, they could be put on and off at will, popped in a drawer or hung on a chair.

Although it is tempting to link the disappearance of tie-on pockets as coinciding with the uptake of handbags, the story is in fact more complex and more interesting. Bags and pockets for women had long coexisted, acting as complementary rather than competing. The Lady Clapham doll (1690 – 1700) in our collections comes complete with sets of clothing and finely-crafted accessories for different occasions. She has a tie-on linen pocket as well as a quilted petticoat with integrated pockets and a gaming draw-string bag in which to keep her gambling money. Instead of seeing bags and pockets as rivals or as succeeding each other in a neat chronology, Lady Clapham's wardrobe encourages us to think of them serving different purposes. She also invites us to think of sartorial practices as not exclusively driven by fashion and aesthetics, but also fitness for purpose and practicality.

It is also expedient to carry about you a purse, a thimble, a pincushion, a pencil, a knife and a pair of scissors, which will not only be an inexpressible source of comfort and independence, by removing the necessity of borrowing, but will secure the privilege of not lending these indispensable articles.

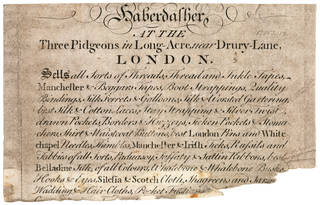

Finding out how women used pockets and what they kept in them is not straightforward. Habitual use of such a commonplace thing was simply not remarkable enough to get much attention. Added to this, very few women in the past left surviving written records, and, if they did, they had little motive to record what was in their pockets when pockets were precisely what they wanted to keep private and secure. Despite these obstacles, there are some ways of peeping inside these pockets of the past. When the theft of a pocket was reported to law officers, the owner would itemise the missing contents, just as we would do today if our handbag was stolen. Delving into records of criminal trials involving such thefts reveals some fascinating insights into what was in the pockets. Additional information from novels, diaries, letters or newspaper adverts for lost pockets also help to piece together this otherwise hidden part of the pocket's story.

D[r]opp'd between St. Sepulchres church and Salisbury court in fleet-street, going down fleet-lane, and crossing the bridge, a pair of white fustian pockets, in which was a silver purse, work'd with scarlet and green S.S. In the purse there was 5 or 6 shillings in money; a ring with a death at length in black enamell'd, wrapp'd in a piece of paper; a silver tooth pick case; 2 cambrick handkerchiefs, one mark'd E.M. the other E5D; a small knife; a key and pair of gloves, and a steel thimble. &c. If the person who took them up will bring them to mr. peachy's at the black boy in the o'd baily, he shall receive a guinea reward, ann no questions ask'd.

The items secreted in pockets provide an insight into the tasks and responsibilities that shaped women's everyday lives. There were keys for street doors, rooms, cupboards, and even for winding watches and locking pocketbooks – all necessary in multiple-occupancy households with lodgers, servants, and apprentices living in cramped conditions with their landlord or employer. For a servant to have their employer's keys in their pocket was a sure sign of trust between them. Female servants may have also owned a lockable storage box in which they would keep their precious, personal possessions. This box would travel with them when they went from one household to another. Unsurprisingly, many women judged that the safest place to store keys and other valuables at night was in their pocket, typically stowed under their pillow.

Women that kept shops, stalls, dairies or taverns, or did any form of paid work, liked to have their small tools such as penknives, bodkins (tool for making holes in leather or cloth), pencils, corkscrews and even their spectacles close at hand in their pockets. During a court case concerning a stolen pocket in 1794, Richard Bullen was able to identify an old green knife 'of no value' belonging to his wife as she had carried it in her pocket since before they were married. And in 1832, another pickpocketing case revealed that Ann O'Dell had a piece of 'stone-blue' – a product used during textile washing to improve the appearance of fabrics, particularly whites – in her pocket, befitting her work as a laundress. Even women who didn't do paid work liked to keep their 'housewife' (a small case that held sewing tools and materials), scissors and thimble with them, ready to tackle whatever cropped up during the day.

With few options for the safe storage of precious objects available to women, pockets were sometimes used to store valuable or prized items. Women of rank often carried startling quantities of ornate little valuables made of precious materials – snuff boxes, personal seals, smelling bottles, toothpick cases, combs, bodkins, pocket-books and pocket-sized almanacs, pencils, silk purses and sometimes watches. Such women might have also carried miniaturised botanical field guides and telescopes to refer to while on walks and rambles.

The snuffbox and smelling-bottle are pretty trinkets in a lady's pocket, and are frequently necessary to supply a pause in conversation, and on some other occasions. But whatever virtues they are possessed of, they are all lost by a too constant and familiar use. And nothing can be more pernicious to the Brain, or render one more ridiculous in Company, than to have either of them perpetually in one's hand.

Women from all walks of life carried cash – sometimes considerable sums – particularly if they were about to pay or collect rent, but purses were not the only way women stored their money inside their pockets. Various court recordings report that one woman used a little wooden box to store her money, another tied hers up in the corner of a handkerchief, another went out dancing with her husband in 1767 and nestled her coins in the snuff inside her iron snuffbox. Conversely, small items of jewellery such as earrings or precious buttons were often kept in pockets in purses or rolled within a 'housewife'. In the proceedings of Old Bailey case t17840114-54, Ambrose Cook was found not guilty of picking the pocket of Elizabeth Adams. Amongst the many items listed as having been stolen from her pocket was a nutmeg grater that was concealing papers, including pawnbroker valuations and receipts. Women's pockets were also used for the safekeeping of other people's belongings, such as their husband's watches or wages.

Contrary to the satirical cartoons and widely reported male opinion that women's pockets were chaotic places, the many ingenious ways in which items were concealed, stored and organised – sometimes using multiple pockets with distinct functions for the items in each – highlights the orderliness, functionality and convenience of these accessories.

Pockets provided a place to keep or hide sentimental items such as letters or portrait miniatures or other mementoes of loved ones. There is also evidence that bones, believed to cure cramp or sciatica, were held in the pocket close to the body of the sufferer. In 1750, Jane Faulkner was found guilty and sentenced to transportation to the colonies for the theft of pockets belonging to landlady, Bridget Bourne. The Old Bailey case proceedings detail many high-value items that were stolen, many of which were missing from the pockets by the time the thief was apprehended and searched. However, a number of objects with no value, including a sciatica bone, were still inside. Lodger, Thomas Draper, took it upon himself to search Faulkner and found all the missing items hidden under her petticoats.

The covert, private nature of pockets meant that they were sometimes used to conceal other secrets. In 1770, in a hearing at the Old Bailey in London, a young servant, Elizabeth Warner, was acquitted of murdering her illegitimate baby daughter after she was discovered trying to hide the afterbirth in a leather pocket. Good use could also be made of capacious and invisible pockets by women thieves in carrying off their loot – in 1807, Hannah Stevens used her pockets to stash three pairs of stockings and seventeen pairs of gloves, and Jane Griffiths made off with two live ducks belonging to her neighbour.

Pockets, and their contents, give us some insight into how women could own, use and think about material possessions and, with those possessions, inhabit and negotiate the social and economic world. The portability of pockets allowed for greater freedom and independence and provided security and concealment for valuables and objects of sentimental value. However, the ever-changing silhouettes and utility of women's clothing over time meant that tie-on pockets became less practical and eventually fell out of favour. Despite this, the story of the pocket continues with campaigners, activists and academics petitioning for women's clothing to feature functional pockets like those featured on menswear.

With thanks to Barbara Burman, independent scholar, and Ariane Fennetaux, Assistant Professor of History, Université de Paris; authors of The Pocket: A Hidden History of Women's Lives, 1660-1900, published by Yale University Press.