A stitch in time, may save nine.

First recorded in Thomas Fuller’s Gnomologia, Adages and Proverbs (1732)

The meaning of the ‘stitch in time’ proverb is well known: if you address a small problem with a little work, you prevent it from becoming a big problem requiring a lot of work. It’s probably no coincidence that this saying, first recorded in the 18th century but likely to have originated much earlier, builds its metaphor on the practice of sewing. Sewing is, and always has been, associated with hard work, prudence and virtue. It has also been predominantly associated with women throughout history, who, for centuries, have been exhorted to practice… hard work, prudence and virtue.

While curating the display ‘A Stitch in Time’, I have tried to address the complex relationships between women, needlework and design. Showing a selection of sewing and knitting tools produced between 1600 and 1900, this display looks at the material aspects and design history of such tools. In doing so, it provokes questions about the status of sewing tools, and how this might have reflected on the women who owned and used them. In this blog post, I’d like to go into a bit more detail about some of the historical details and questions which, as with any display, I couldn’t fully cover in the 60-word labels accompanying each object.

Before doing so, it’s worth explaining the women-centric nature of the display and its interpretation. While sewing and femininity are the focus here, there is a rich history of men sewing in various capacities. Sailors and soldiers, for example, made and mended their own clothing – in fact, life on board an 18th century warship was punctuated by ‘make and mend’ day, in which normal duties were suspended to allow sailors to repair their clothing (and indulge in merrymaking). The tailor, of course, was the supreme example of the man-who-sewed, working primarily on men’s clothing and more complex forms of women’s dress, such as the pleated sacque gown fashionable between the 1750s and 1770s. What the tailor and the sailor have in common, however, is that they sewed because they had to – either to make a living, or because nobody else was available to work for them. While many women also sewed out of necessity – on which more later – the practices of sewing, embroidering and knitting were constructed as suitable, even necessary, amusement and activity for them. From the complex embroideries designed and made by Elizabethan aristocrats, to the simple Berlin-work kits sold to bourgeois Victorian housewives, needlecraft in all its forms was seen as an essential component of female virtue. As the following quote suggests, sewing was compatible with the domestic, self-sacrificing and industrious pursuits of the ideal woman:

[Sewing] fills up the interstices of time… It accords with most of the indoor employments of men, who… do not much like to see us engaged in anything which abstracts us too much from them. It lessens the ennui of hearing children read the same story five hundred times. It can be brought into the sick room without diminishing our attention to an invalid.

Letter from Mrs Trench to Mrs Leadbeater, May 1811

We can think of sewing as a kind of performance, despite its domestic setting – a way for women to prove their femininity and suitability as wives, lovers and mothers. Like any good performance, sewing needs its props, and the tools used by women to prepare and execute their work were often objects of art in their own right. They reflected the latest in both decorative styles and in manufacturing technology, lending an air of status to the act of sewing. The cut steel buttons and work holders on display, for example, were at the forefront of both fashion and technology in the late eighteenth century. Cut steel had its origins in the sixteenth century, but was developed and refined by industrial pioneers such as Matthew Boulton in the eighteenth. The technique involved cutting facets onto steel studs, many of which were miniscule and required great skill to work, which were then riveted to a steel or brass backing. The end result sparkled under candlelight and resembled gemstones – indeed, it was often used in jewellery design – so decorating a functional tool in this manner suggests that it was intended to impress.

As well as being highly decorative, many sewing implements also carried coded messages in their design. Thimbles are a good example, as they were often presented as gifts and therefore their mottoes and images can be read as a message for the recipient. Needless to say, such items tended to reinforce the prevailing view of femininity, conveying messages on an object intended for use in a virtuous, industrious context. Thimbles often displayed messages relating to love and marriage, which was in most cases the only realistic objective open to middle- and upper-class women until around 1900. For example, the very elaborate seventeenth-century silver thimble on display was probably a gift for a bride, or perhaps a mistress, covered with erotic and fertility motifs. It is decorated with a wedding scene, nude figures in compromising positions, interspersed with rabbits, and topped off with a crowned heart and the motto La Puissance d’Amour / Mon Desir n’a Repos (The Power of Love / My Desire Has No Rest). The expectations would have been clear to the woman who received this thimble: love, marriage, children, and lots of sewing!

It’s important to remember that, legally speaking, a married woman in Britain was technically unable to call any property her own, until the first Married Women’s Property Act was passed in 1870. The legal principle of coverture meant that a wife, or feme couverte, had no individual status under the law, and thus could not own property or enter into any contract independently of her husband. This also meant that the legions of women who earned money in the needle trades could not, if married, claim their wages as their own. Sewing tools, being regarded as ephemeral, feminine and relatively low in value, were among the few types of portable paraphernalia which women could informally bequeath to daughters, sisters and friends. As such, they had a special resonance, both for sentimental reasons and as a means of subverting the established gender hierarchy. The silver filigree thimble on display, for example, is monogrammed ‘M.R.’, suggesting that its owner was particularly anxious to mark the object as her own property.

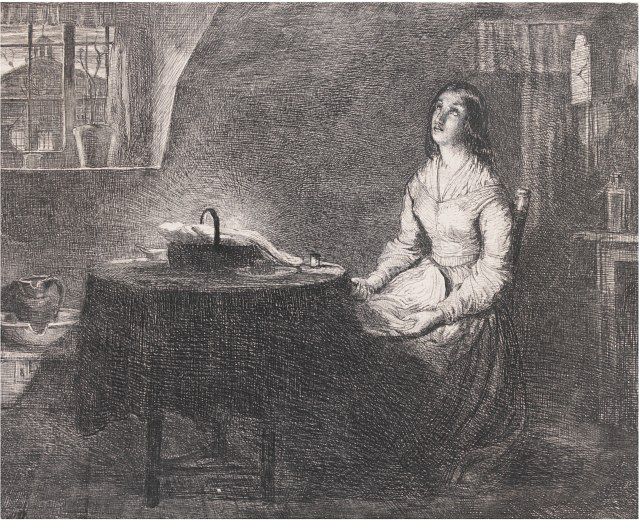

Decorative cut steel and silver sewing tools were, of course, the preserve of wealthier women (or, rather, of women with wealthy husbands or fathers). Those women earning their keep by the needle were in rather a different position – no elegant tools for them. Poor women and girls had few respectable options for earning their own living, and the needle trades – such as dressmaking, shirtmaking and millinery – were often their only resort, despite the appallingly low pay. Until the advent of the clothing factory in the second half of the nineteenth century, most work was ‘piece work’ done at home by women and children. So poor were the wages and conditions that many women nevertheless turned to prostitution throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as a means of supplementing their inadequate incomes. The work, which often lasted from dawn until midnight, was injurious to the eyesight and the spine, and the poor pay was compounded by the fact that women had to pay a deposit to their overseer for the materials, repayable upon delivery of goods. This problem attracted the attention of social reformers, particularly after the 1843 publication of The Song of The Shirt, a poem in which a poor woman tries to care for her sick child by taking on piecework for meagre money.

Stitch! stitch! stitch!

In poverty, hunger, and dirt,

And still with a voice of dolorous pitch

She sang the “Song of the Shirt.”

Excerpt from The Song of The Shirt by Thomas Hood (1843)

For rich and poor women alike, sewing changed dramatically with the advent of the sewing machine, Various attempts at a machine had been made during the 1830s and 1840s, but the first commercially and technically successful one was patented in the United States by Isaac Singer, in 1851. The sewing machine was revolutionary as a labour-saving device but, beyond that, the status quo remained intact. Women may have been able to sew faster and more efficiently, but the sewing machine merely removed the needle from their hands – they were still the ones operating the treadle. Nonetheless, it represented modernity, and some women used their ‘traditional’ sewing accomplishments to upset the established social order. From making divided cycling skirts – trousers, really – to sewing protest banners for suffrage organisations and trade unions, sewing could be a political act, and the sewing machine contributed to this.

‘My dear Jessie, what on earth is that bicycle suit for?’

‘Why, to wear, of course.’

‘But you haven’t got a bicycle!’

‘No, but I’ve got a sewing machine’

‘Gertrude and Jessie’, Punch magazine, 1895

Like the elegant implements that preceded it, the early sewing machine was most definitely a status object. Decorated with lacquer and housed in a fashionable cabinet, these machines were designed to sit at the heart of the drawing room, advertising the domestic virtue of the lady who occupied it. It was not until prices began to drop after 1900 – and poorer women could buy them on hire-purchase – that the sewing machine became strictly utilitarian. The increasing availability of shop-bought clothing meant that home sewing lost its cachet, and became a thrifty expedient to be hidden where possible. Advertisements for sewing machines reflect this shift, with the earliest ones extolling the style and beauty of their product, to be replaced with assurances of discretion and portability once the machine lost status. The sewing machine in its heyday marked the high point of home sewing as a leisure pursuit, praised in ladies’ journals and illustrated magazines for its efficiency and pleasantness. It also, however, marked the beginning of the end. The technological and manufacturing advances that enabled the production of sewing machines also meant that factories could use the machines to mass-produce clothing that was cheaper and more consistently fitted and finished than the home-sewn equivalent.

Home sewing has never really gone away, even if it ceased to be such a key component of feminine identity in the twentieth century. The Second World War saw a major revival, due to cloth rationing and the official ‘Make Do and Mend’ programme. More recently, sewing, knitting and other needle crafts have been reclaimed by the feminist movement, seeking to elevate the artistic status of techniques ignored by the mainstream art establishment because of their feminine and domestic associations. Since Rozsika Parker published The Subversive Stitch in 1983, sewing has re-emerged as a political act, with ‘craftivism’ putting traditional crafts and sustainability at the heart of protest and activism. For every stitch in time, there is a common thread binding them together.

‘A Stitch in Time’, a free display, opens at the V&A on 5th May.

I have been commissioned to write an academic monograph on Frances (Fanny) Trollope. Trollope’s mother died when Fanny was about 5 and she was brought up by her father. She did not therefore have a maternal model from whom to acquire domestic skills, including sewing! She was notoriously ill-presented! I am trying to track down some secondary sources to put in some commentary on the importance of sewing even for middle-class women that expands the comments in your blog. Are you able to recommend something please? Many thanks. Carolyn Lambert

Hi there. I wonder if you have any information on a company that made sewing kits, named DLR & Co? I suspect they are either UK based, or somewhere in Europe. My late grandmother, born in England, passed on an old sewing kit to me, which has ivory handles. This company inscription is on it, and I am trying to find out how old this kit is.

Any advise will be greatly appreciated.

Thank you,

Belinda