129 years ago today, Princess Beatrice, the beloved daughter of Queen Victoria, married Prince Henry of Battenberg.

Princess Beatrice was the youngest of Victoria and Albert’s nine children. Her mother became increasingly dependent on her after the death of her father in 1861, when Beatrice was only four years old. While her siblings were strategically married off to royal European households, the Queen intended for her youngest child to stay home as her support and companion. However, in 1884, Beatrice met Prince Henry, generally referred to as Liko, and returned home from a trip to Germany with the news that she wished to marry. This announcement was apparently met with a few months of disagreement and tense silence between the mother and daughter.

However, the Queen became reconciled, and in the end supportive, of their relationship – on the condition that the couple would live with her. This change in emotion can be observed in the descriptions Victoria wrote in her journal of the wedding preparations, the day itself and of Beatrice’s wedding clothes. In her entry for the 21st, on the night of which a celebratory dinner was held in a grand tent, Victoria states that ‘everyone was so pleased to see how happy & bright darling Beatrice & Liko looked.’ To this dinner, Beatrice wore ‘one of her trousseau dresses & [her mother’s] rubies’. The Queen also lovingly describes leading Beatrice into the drawing room that morning, where she had ‘placed my gifts for darling Beatrice’. These gifts included Victoria’s ‘ruby & diamond parure, which dearest Albert had arranged & collected, & . . . a beautiful fan, designed & executed by the female students of the School of Art at South Kensington, & mounted in England.’

When the wedding day itself arrived, the Queen’s account of the occasion was no less expressive. Opening the entry with the phrase ‘Darling Beatrice’s wedding day’, the entry is full of references to clothing and jewellery. In particular, Victoria seems to have demonstrated her support of the union through gifts and loans of pieces she wore at her own wedding. First of all, the Queen ‘gave a ruby half hoop ring, which my Uncle, the Duke of Sussex gave me, when I married.’ Secondly, and touchingly, Victoria describes her emotion on seeing ‘Beatrice trying on her wedding dress, which is very pretty…with my own dear wedding lace draped in front.’ These sartorial ties between the mother and daughter imply a bid for a continued connection between the two. Equally, by dressing her daughter in the pieces which marked the start of her own happy marriage, the Queen may well have been hoping to pass on some of this parental success and luck to the new union.

Perhaps one of the most sartorially symbolic gestures made between Beatrice and her mother on her wedding day was that the bride dressed in her father’s room. This room was an obsessively preserved space, in which the sheets were changed daily as though Prince Albert was still alive. Queen Victoria encouraged Beatrice to dress in there, ‘in order that I might be near her’, and in doing so imbued the day with a sense of her lost father’s presence. As her father had passed away when she was a little girl, this ghostly conservation of his place in the family’s home was her only adult connection to him, and one which they honoured in this way on her wedding day.

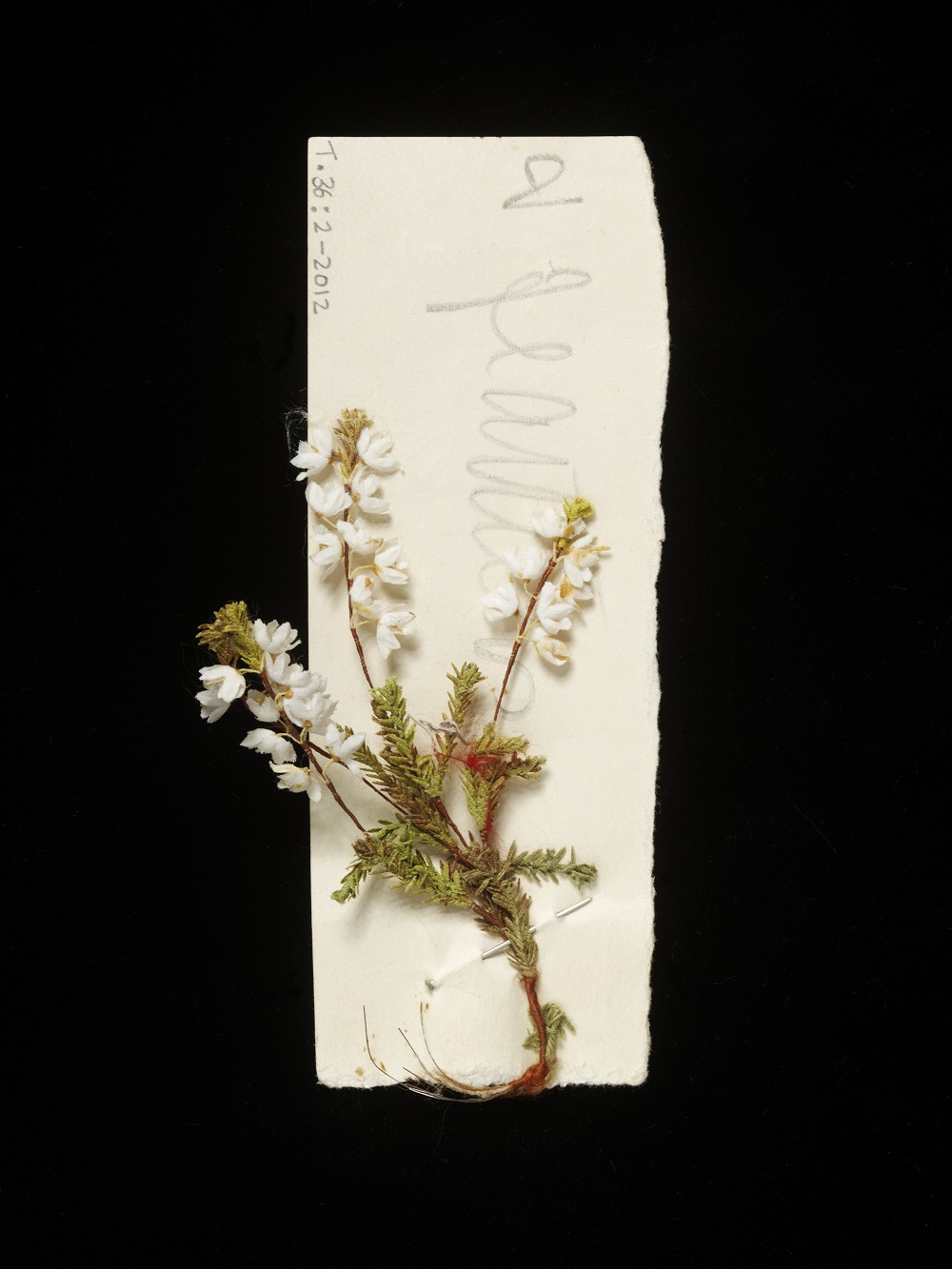

This talismanic preservation and passing on of objects and spaces for Beatrice’s wedding is reflected in a set of pieces we have on display in the exhibition. The Princess had her trousseau and wedding dress made by Mrs Stratton, one of London’s most exclusive dressmakers. Caroline Gammack, Mrs Stratton’s stock-keeper, perhaps caught up in the excitement of having such a renowned customer, preserved small cuttings of each fabric selected for Beatrice’s garments. As the swatches entered our collection as a set in 2012, some 127 years after the wedding had taken place, they demonstrate the emotional investment such pieces are often protected and preserved by.

Queen Victoria also described her youngest daughter’s wedding day as ‘splendid, a very hot sun, but a pleasant air’. So, if this current weather lasts, we may be in for a similar day ourselves, nearly a century and a half later.