Wedding dresses are designed with a particular ceremony and site in mind. Beyond the symbolic and ceremonial associations incorporated in its design, such a dress is also created to dazzle and to move in a very particular setting. Therefore, whether it is decorated to catch the candle light of a church, or cut to swirl as a bride makes her way down a staircase, a wedding dress is made with an occasion – and a grand entrance – in mind.

For a modern garment to be so sartorially site specific is very unusual. The most prized pieces in our wardrobe tend to be so for their adaptability – with fashion magazines forever celebrating an item’s ability to go ‘from day to night’ – and so their aptitude for making us feel fantastic in a variety of settings. While you might originally buy a dress for a particular party or even an interview, that incentive for selection softens as you wear the piece to other places. As a result, outside the realms of state dress or uniform, few garments are created to be worn in one venue and one way.

Wedding dresses are an exception to this rule.

Sarah Boddicott married her second cousin Samuel Tyssen on 28 September 1779. The ceremony took place at St John’s church in Hackney, which, by 1789 had a capacity of 1000. The audience for the couple’s wedding a decade before can, therefore, be expected to have been large. Sarah wore a dress made of white silk woven with silk strip and trimmed in silver fringe.

At that time, church law stated that weddings had to take place between 8am and 12pm, meaning that Sarah will have married in daylight. The sweeping back of Sarah’s dress, along with the sparkling silver strips, will have attracted this light. Equally, candles were common in churches and their flames will have made the silver fringe on her dress glimmer as she moved up the aisle.

Meanwhile, when Eliza Clay married Joseph Bright in 1865 at St James’s church in Piccadilly, London, she wore a silk-satin wedding dress with a wide skirt. St James’s church has a long aisle and a high, curved ceiling. Gas lighting began to be used in urban churches from the mid nineteenth century onwards. This lighting will have bounced on both the painted ceiling and wedding dress, making the fabric glow as Eliza moved.

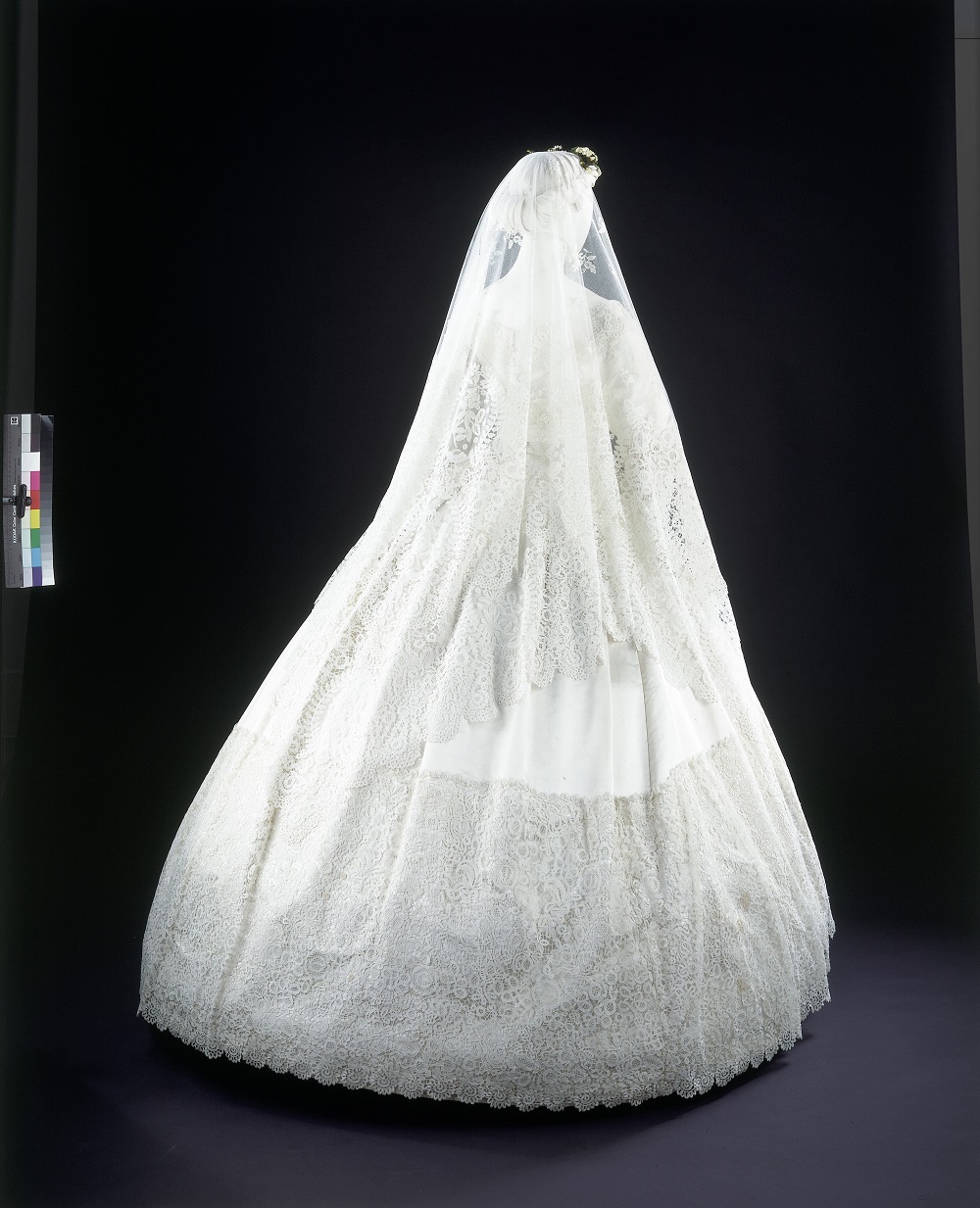

Many visitors to our exhibition have commented on the detailing of the back and trains of the dresses on display. This detailing is a consequence of the fact that, for the majority of a wedding, the bride is viewed by her guests from behind. It is a testimony to her confidence, and desire for attention, that Margaret Whigham commissioned Norman Hartnell to design her a wedding dress with a train that would be a match for the Brompton Oratory’s particularly long and wide aisle. The 18 foot result, embroidered in pearl bead embroidered star flowers, was more than up to the task.

A modern wedding dress must be built to successfully and stylishly move from service to celebration. This may well mean that the dress’s design must be site appropriate for at least two venues and stages of the occasion. In the case of Kate Moss’s Galliano gown, a wedding dress which appears pixyish by the morning sun may glitter flirtatiously by the lantern light of an all-night party.

With many weddings moving away from the context of a church, the sites these modern dresses are specially designed for vary from stately homes to bunting-lined fields to beaches. As suitable for dancing until dawn as for making a sweeping entrance, these modern dresses are predominantly designed to be worn for just one day. This brevity of wear lends them the luxury of being truly specific to the occasion, scene and woman which they adorn.