‘… [your] name and glory is not only renowned among one people and nation, but across the earth, wherever scientific and learned studies are practised and honoured.’

These rather adulatory words were penned to describe today’s ‘born on this day’ star, Ole Worm, the Danish physician, professor, antiquary, and collector extraordinaire born in 1588. As well as being the bearer of a most memorable name, Worm was an individual whose work had both social and scientific significance in numerous disciplines, including museology, ethnology and archaeology, during the 17th century.

The praising words quoted above come from a 1644 letter sent to Worm by August Buchner from Wittenburg. His eulogising of Worm’s virtue and fame continues, as he describes how numerous European countries:

‘marvel at my Worm and count him among those who, in addition to the pursuit of other great arts, have won immortality for themselves through the study of antiquities and the finer sciences.’

[letter translated by Vladimar Tr. Hafstein]

Worm (who often went by the Latinized form of his name Olaus Wormius), was an inquisitive and enquiring fellow, keen to learn in the fields of both Arts and Science. He was an ardent and almost ‘perpetual student’. Following grammar school, he studied theology at the University of Marburg, achieved a doctorate in Medicine from the University of Basel and later a Master of Arts from the University of Copenhagen.

The son of Willum Worm, who served as the mayor of Aarhus (Denmark), upon his father’s death he received a considerable inheritance – which was no doubt useful to support his ongoing academic edification.

In 1605 he set out on a ‘Grand Tour’ across Europe to continue his education. During this time he served visited museums and collections, studied anatomy, theology, philosophy and medicine, and also worked as a private tutor.

His tour of Europe continued for a number of years, ending with a period spent in London before he took up a position teaching medicine at the University of Copenhagen. Worm’s great talents led to him later being appointed as personal physician to King Christian IV of Denmark.

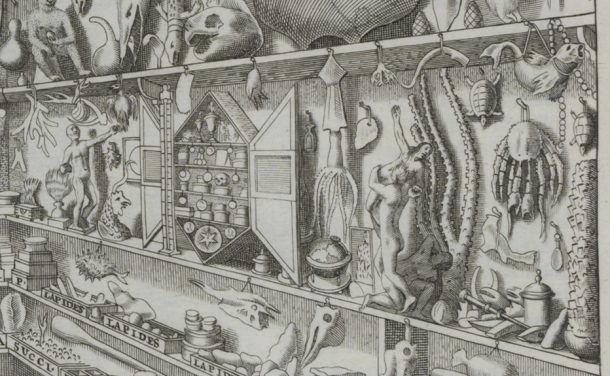

As a natural philosopher, Worm assembled an extensive teaching collection of minerals, plants, animal specimens and man-made objects from all over the world. As a self-confessed collector of various oddities it is this collection which is of most interest to me!

Worm was working during a period of widespread enthusiasm for creating personal collections of eclectic objects. These collections were intended to provoke curiosity and wonder at both the variety of God’s creation and man’s ingenuity. They often included works of virtuoso artistry and craftsmanship, strange natural phenomena, and rarities from around the world.

It was during his tour of Europe that Worm started to gather together specimens that formed the start of his collection. However, the majority of the collection appears to have been amassed following his travels, through various correspondents throughout Europe.

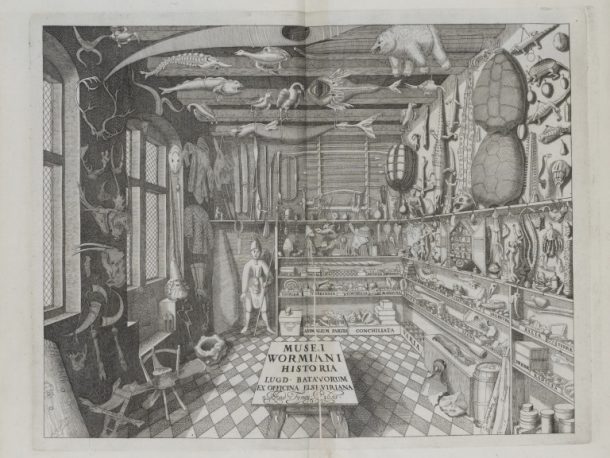

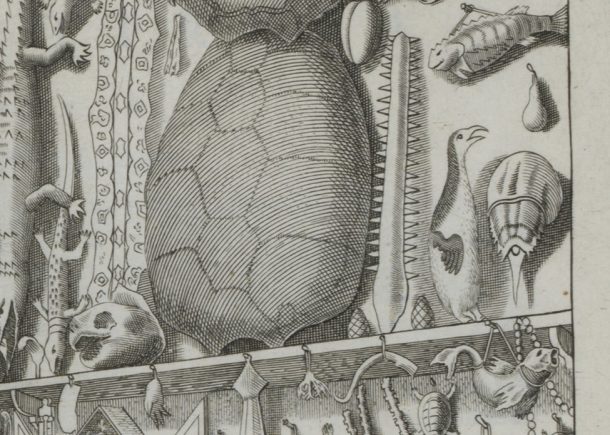

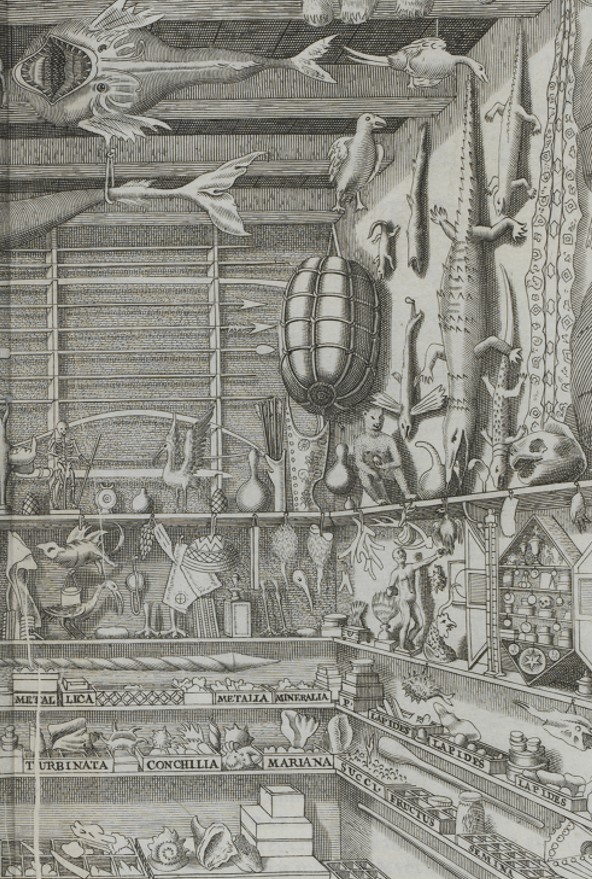

Worm categorised, ordered and displayed his vast collection and compiled a painstaking inventory of all his natural and artificial wonders. Tantalisingly, the appearance of this Museum display is suggested in the detailed frontispiece above, which will be displayed in The Cabinet of the Europe Galleries.

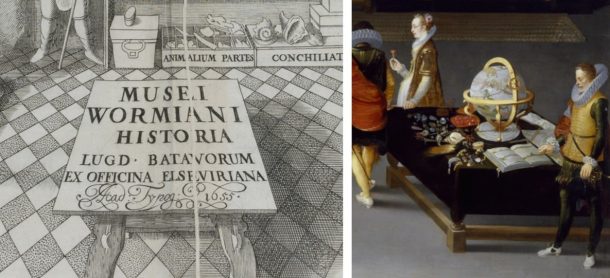

The frontispiece was produced to accompany a catalogue based on Worm’s comprehensive inventory. The catalogue was edited by his son, Villum Worm, and published the year after his death in 1654, with the rather overly specific title: ‘Museum Wormianum : seu, Historia rerum rariorum, tam naturalium, quam artificialium, tam domesticarum, quam exoticarum, quae Hafniae Danorum in oedibus authoris fervantur’ – which roughly translates as ‘Worm’s Museum, or the History of Very Rare Things, Natural and Artificial, Domestic and Exotic, Which Are Stored in the Author’s House in Copenhagen.’

Whether or not the frontispiece is a truly accurate depiction of how the collection was displayed, it still suggests concepts of order and categorisation of his collection, reflecting the four categories by which the catalogue divided the collection: mineral, plant, animal and ‘artificialia’.

In a letter of 1639, Ole Worm explained his rationale for creating his museum:

‘As to the display of curiosities in my museum, I have not yet completed it. I have collected various things on my journeys abroad, and from India and other very remote places I have been brought various things […] that I conserve well with the goal of, along with a short presentation of the various things’ history, also being able to present my audience with the things themselves to touch with their own hands and to see with their own eyes, so that they may themselves … acquire a more intimate knowledge of them all.’

[translation by Vladimar Tr. Hafstein]

Worm’s enthusiasm and aim to share reliable knowledge with others, is repeated in the preface of the catalogue. Here he describes his aim to bring together a collection of ‘the most varied and beautiful phenomena of nature‘ that could be ‘brought to the youth, so that through it the youth could be brought up from the quicksand and darkness of errors and into the clear light of day and the most beautiful mediation of God’s works.‘

His goal for the catalogue was to present his collection and the accompanying research ‘for the observation of everyone who felt attracted to nature‘.

[translation by Vladimar Tr. Hafstein]

The copy of ‘Museum Wormianum’ that will be on display in the Europe Galleries is one of three editions, printed in 1655, by different members of the Elzevier family. This indexed publication contains woodcut illustrations of the collection, accompanied by Worm’s speculations about their form and meaning.

Worm has been described as straddling the line between modern and pre-modern science. In the 17th century the modern, empirical approach to scientific enquiry was still being developed and Worm’s periodic adoption of this approach to his studies had both social and scientific significance.

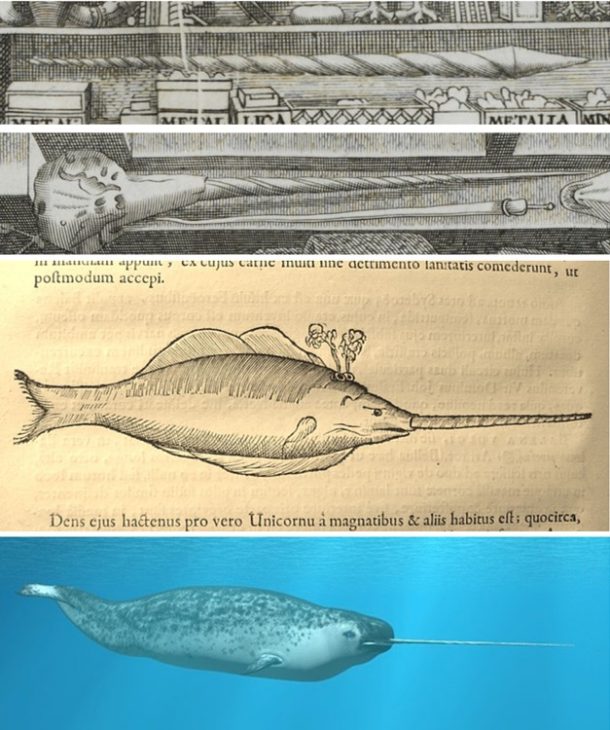

One occasion of his application of an empirical approached resulted in his 1638 conclusion that unicorns did not exist. This came at a time when a common belief in unicorns was supported by the existence of what were purported to be unicorn horns. Worm was one of the first to publicly refute such beliefs, determining that these ‘unicorn horns’ were really from narwhals.

The catalogue is dedicated to Frederik III, king of Denmark and was published the same year in which he bought Worm’s collection. Items from Worm’s collection survive in the Danish royal collection today, including a marble globe, a miniature shoe carved from a cherry stone, a gold ring, a bronze dagger and an Icelandic drinking horn. Around forty items are currently on public display at the Natural History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen.

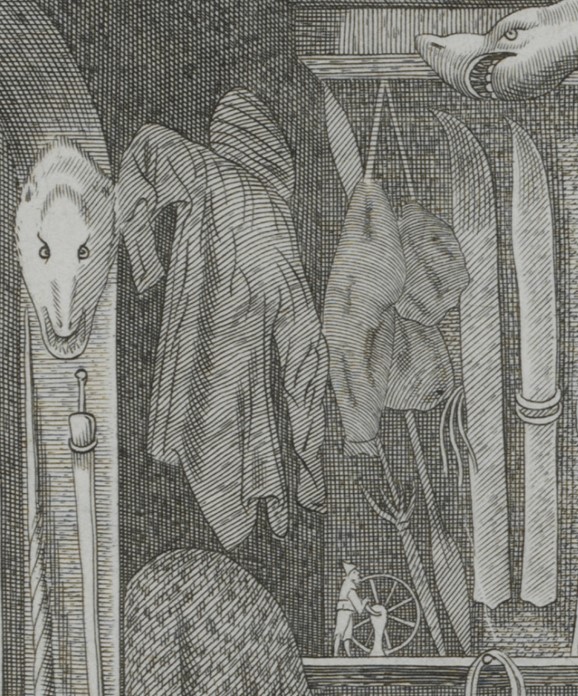

I have enjoyed closely examining the frontispiece and taking an imaginary walk around Worm’s well-stocked museum: looking in the various boxes; trying to identify unusual objects; being slightly perturbed by the various animals looming above etc.. I was therefore interested to see that artist Rosamond Purcell has made this somewhat a possibility.

In 2004-5, Purcell produced ‘Bringing Nature Inside’, a meticulous re-creation of Worm’s Copenhagen museum as depicted in the frontispiece. Originally part of the exhibition ‘Rosamond Purcell: Two Rooms’, organized by the Santa Monica Museum of Art and curator Lisa Melandri, the installation travelled to other institutions before settling in the Geological Museum at the Natural History Museum of Denmark in 2011.

Until I am able to make it over to Denmark, I shall continue with my two-dimensional, imaginary exploration of Worm’s extraordinary ‘Museum Wormianum’ …

GREAT!!!

I am trying to track down which museum is touting the authentic green pea from Hans Christian Andersen’s story (unless someone has removed it) in Copenhagen?… or even the seven peas (from the Swedish version?) or perhaps the dried-out folded-over petal from that story from Seneca the Younger ? Any suggestions?

The author commented on the figure of a man turning a crank attached to a large wheel. This may be what is known as a great wheel, which was used to power many types of machinery by means of a belt running around the great wheel and a much smaller wheel on the machine. Using a lathe as an example, a very large powering wheel would turn the lathe at high speed for working wood of relatively small diameters; a smaller powering wheel would be used to provide slower turning speed for working larger diameter wood stock, or for working metal.