Cameraless techniques have been exploited and reinterpreted by successive generations of image makers and continue to be used by contemporary artists today. While related to the conventional practices of photography, cameraless images offer an alternative, experimental, radical and often revelatory form of vision.

The great American photojournalist and documentary photographer Dorothea Lange declared, "The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera". Cameraless photographers take up the implied challenge of her statement quite literally, abandoning the camera at the outset in favour of a more direct and readily metaphorical rendering of photographic phenomena.

There are several ways of making cameraless images – such as photograms, radiographs, luminograms and chemigrams.

Photogram

"The photogram ... which embodies the unique nature of the photographic process, is the real key to photography. It allows us to capture the patterned interplay of light on a sheet of sensitised paper without recourse to any apparatus."

The most common technique of cameraless photography is the photogram, a term that encompasses all images made simply by the contact of objects on light-sensitive surfaces. Photograms are generally unique and reproduce an actual-size image of the object that blocks light from the light-sensitive surface. The resulting silhouette is a trace, a direct translation of the object's touch and presence.

William Henry Fox Talbot

Fox Talbot (1800 – 77) was the first to experiment and systematically explore the potential of the photogram technique on paper. Talbot favoured using botanical subjects and samples of fabrics, suitably flat objects that created pleasing patterns when placed under glass on sensitised paper in the sun. He quickly grasped the concept that the inverted tones of these resulting 'negative' images could be copied by placing them in contact with additional sheets of sensitised paper and repeating the process to produce positive prints. This sparked the revolution of mass production in photography. In this respect, we have the cameraless photograph to thank for that innovation.

Anna Atkins

Fox Talbot's contemporary, illustrator and botanist Anna Atkins (1799 – 1871), capitalised on both the practicality and beauty of photograms to specialise almost exclusively in images of botanical specimens. Atkins employed the same basic techniques as Talbot, but used cyanotype paper, which produced Prussian blue images that could be developed simply in water.

Atkins is credited with being the first woman photographer to produce a photographically illustrated book, British Algae: Cyanotyoe Impressions (1843), which she followed later with Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns (1853), and British and Foreign Flowering Plants and Ferns (1854). Atkins was already a skilled technical illustrator by the time she took up cyanotype photographic process invented by Sir John Herschel in 1842. A sheet of paper was brushed with iron salt solutions and dried in the dark. After exposing an object on the paper in sunlight for a few minutes the paper was washed in water. Oxidation produced a white image on a brilliant blue, or cyan, background.

From the 1880s, the cyanotype process was used for copying engineering and architectural drawings, giving rise to the term 'blueprint'.

Floris Neusüss

Floris Neusüss (1937 – 2020) dedicated his whole career to extending the practice, study and teaching of the photogram. Neusüss brought renewed ambition to the photogram process, in both scale and visual treatment, with the Körperfotogramms (or whole-body photograms) that he first exhibited in the 1960s. Since then, he has consistently explored the photogram's technical, conceptual and visual possibilities.

In the film below, Neusüss reveals his preparations to make a photogram of a window at Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire, England, that formed the subject of William Henry Fox Talbot's first photographic negative, made there in 1835. In the Abbey's grounds Neusüss also demonstrates the creation of cyanotype photograms using fern leaves, recreating the methods of the very first photographs.

Susan Derges

During the 1990s, Susan Derges (born 1955) became well known for her photograms of water. To make these works, she used the landscape at night as her darkroom, submerging large sheets of photographic paper in rivers and using the moon and flashlight to create the exposure.

Within seeming chaos, Derges conveys a sense of wonder at the underlying orderliness. She examines the threshold between two interconnected worlds: an internal, imaginative or contemplative space and the external, dynamic, magical world of nature.

In the film below, Derges prepares to make a photogram outdoors and discusses her use of water as a metaphor for transformation.

Adam Fuss

Drawing upon his childhood memories and personal experiences, Adam Fuss's (1961) works are centred around the discovery of the unseen, the expression of the ephemeral and the universal themes of life and death. As well as mastering numerous historic and modern photographic techniques, Fuss has developed an array of symbolic or emblematic motifs.

In the film below, Fuss takes us through the process of creating a series of daguerreotype photograms of butterflies. Now a largely obsolete photographic medium, the daguerreotype was first used in the 1840s. Fuss also uses live snakes in his studio, making images that explore the animal's symbolic and metaphorical meanings.

Radiographs

The discovery of X-rays in 1895 revitalised and expanded camerless possibilities. Here was a kind of photogram that not only revealed the silhouette of an object placed in front of the photographic surface, but also penetrated matter and revealed its hidden inner structure. The medical applications of these radiographs were obvious, but their startling visual impact was also irresistible. X-rays gave tangible evidence of a formerly invisible world beyond the capabilities of human vision.

Alan Archibald Campbell-Swinton (1863 – 1930) was a pioneer in testing the new discovery for medical applications, opening the first radiographic laboratory in Britain in 1896. His experiments in imaging continued, and in 1908 he published an explanation of 'Distant Electric Vision' – what we now know as television.

Nick Veasey

Nick Veasey (born 1962) has perfected X-ray images and achieved an ambitious scale of subject matter, such as motor vehicles, that were beyond the reach of early practitioners. Since 2016, the V&A has been collaborating with Veasey to make high-quality X-ray studies of our Fashion collections, including iconic garments by Cristóbal Balenciaga, and objects that featured in our Fashioned from Nature exhibition (2018 – 19).

Photograms and radiographs were rediscovered in the early 20th century for their aethsetic value by artists of the avant-garde art movements including Dada and Surrealism, and those turning their backs on traditional techniques in favour of abstraction. Chief among these was László Moholy-Nagy who began to experiment with camerless processes in 1922. Man Ray stylishly applied photograms (or what he called 'rayographs', after his own name) to his artwork and commercial commissions with great effect. Fellow American Curtis Moffat moved to London in the 1920s where he set up a portrait studio and design emporium, exhibitied his photograms and used them as schemes in Modernist interior decoration.

Luminograms

Garry Fabian Miller

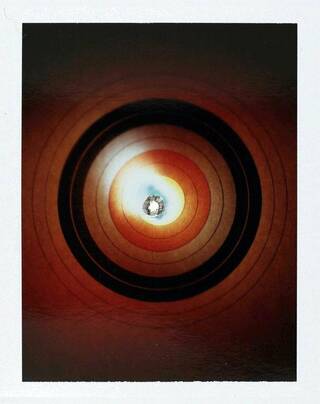

Garry Fabian Miller (born 1957) has devoted his career to a long-term visual and philosophical enquiry, removing the camera as a way of paring back the fundamentals of photography: light and time. Many of his works are luminograms, created by shining a light through glass vessels and over cut paper forms before registering on photographic paper. His works explore the cycle of time over a day, month or year, through controlled experiments with varying durations of light exposure. His works are enriched by being seen in sequences that explore and develop a single motif and colour-range. Often, the images are conceived as remembered landscapes and natural light phenomena.

To make the image Breathing in the Beech Wood, Homeland, Dartmoor, Twenty-Four Days of Sunlight (2004), Fabian Miller gathered leaves over 24 days in spring. He placed them into a photographic enlarger, using the leaves instead of a negative or transparency to project their image onto photographic paper. Each vertical row represents one day of collecting and printing. The arrangement shows the gradual effect of chlorophyll entering the leaf to make it green. It offers a comparison between this process and photography, both of which rely on the transforming power of light.

This film takes a revealing and evocative look at Garry Fabian Miller's working environment:

Chemigrams

Chemigrams are made by directly manipulating the surface of photographic paper in full light, often with varnishes, oils, syrup or wax and photographic chemicals, and sometimes inscribed with handmade marks. Documented experiments are often an important part of the process.

Pierre Cordier

Pierre Cordier (born 1933), a pioneer of this distinctive form of cameraless photography, describes his work as a "mutation", as "hybrid" and "marginal" – fake photographs of an imaginary, improbable and inaccessible world. His chemigrams are full of visual and linguistic puzzles.

Cordier's fondness for labyrinthine patterns is shown in his works that reference the Argentine writer, poet and philosopher Jorge Luis Borges. They are composed of letter forms that spell out Borges's poem La Suma. The letters, however are almost impossible to decipher, their shapes joining together as paths forking in different directions.

In the film below, Cordier is seen in his Brussels studio, working more like a painter or printmaker than a photographer, as he replaces the canvas or printing plate with photographic paper. Using photographic chemicals – as well as varnish, wax, glue, oil, egg and syrup – he creates enigmatic images that are impossible to realise by any other means. In Cordier's work, the process itself becomes the artwork and his style is his technique.

Marco Breuer

Marco Breuer's (born 1966) 'photographic recordings' also use chemigram techniques. Breuer pushes and test the limits of what different varieties of photographic paper are designed to do, often subjecting them to scraping, burning, folding, puncturing or other interventions to create abstract compositions. Most traditional photographs record a single instant; by contrast, Breuer's accumulate scars over time.

Helen Chadwick

Other artists have opted for camerless methods, not as their main medium but more for their appropriateness to realise a concept. Helen Chadwick (1953 – 96) made sophisticated and unconventional use of photocopies to create sublime collages. In Of Mutability (1986), Chadwick places her own body and other objects on a photocopier to create an ethereal world of figures appearing to float in a pool.

Cornelia Parker

Cornelia Parker (born 1956) has often used photography to harness a conceptual or linguistic idea into visual form that would be difficult to capture in any other way. In her deceptively simple photogram, Bated Breath: Fluff and Dust from the Whispering Gallery, St. Paul's Cathedral, London, 1997, dust, the enemy of conventional photography, becomes the subject and the means of evoking a delicate sound and sense of awe. Parker describes the making of this image: "I was on my hands and knees in the hushed gallery, trying to cope with my fear of heights, when I focussed on the felted layer of dust that had collected on the edges of the parapet. This dust formed an accumulated acoustic, built up over time by the thousands of whispering visitors. Later, trapped between the glass, the fluff and dust was used as a negative to produce a photogram."

Recent advances in photographic technology and the demise of traditional cameras seem only to have increased both the inventiveness of artists who use camerless techniques and the growing public fascination for camerless photography. Such images challenge preconceptions of photography as a representational and reproductive medium. If at times ambiguous and resisting form classification, they leave open a welcome space for imagination.